John Tsai, AIA, first moved to Houston when he was six years old. He and his parents were immigrants. In the great horizontal city, stranded in a sea of bedroom communities and strip malls, Tsai found his first awareness of the power of built space in a much-overlooked but ubiquitous infrastructure.

“My earliest memories relate to exploring the storm drain tunnels,” he says. “Primarily, what I remember is the way they branched through all these neighborhoods; their darkness and the heightened awareness of sound, texture, and compression; the way the temperature changed — I think that really got to me. It changed how I perceived my everyday surroundings.”

Tsai went to Cornell University, where he majored in architecture. In San Francisco, he worked for Pfau Architecture for a little over a year, then returned east and enrolled in the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Graduating with an M.Arch, he moved back west and worked for Frank Gehry. Though living in Los Angeles, Tsai didn’t get to see much of the city. He was in the office around the clock. “That’s the first time I was exposed to urban design from the perspective of architecture,” he says.

Tsai met his wife in Los Angeles. She was also from Houston, and the pair decided to move back home. He became an adjunct faculty member at the University of Houston and started his own firm — JT ARC Studio. This was 2007. Since then, Tsai has split time between teaching and practicing.

From the start, JT ARC has taken on projects of all types, from residences and restaurants to mixed-use and urban schemes. “I didn’t want to specialize,” Tsai says. “I like switching scales.” That openness to typology feeds into the studio’s design approach, which is about finding the opportunities in any given project’s constraints.

Moving forward, Tsai hopes to grow the practice organically (it is currently three, including Tsai, his associate Robert Mazzo, and an intern). He is invested in the potential of slow architecture and the idea that designers can improve every part of the built fabric — an observation that has been all the more apparent in Houston since Hurricane Harvey. “Harvey changed the ways developers are pushing projects,” Tsai says. “There’s a lot of room for architects, even small practices, to get involved and rethink typologies.”

Friendship Road

Completed in 2018, this 2,700-sf single family home creates programmatic and spatial opportunities in the cavity of its gable roof. Bedrooms are located above the residence’s more public functions — kitchen, living room, dining zone, and sitting room — and volumetric gaps along the house’s length vary internal spatial relations and open up outdoor pockets. Compressing habitable spaces into the “attic” kept the footprint slim and made connections among interior functions more intimate. Where the gable roof profile is too low to occupy, the architects used the space for visual openings between levels, seasonal storage, infrastructural compartments, a pull-out bed, and shelving nooks.

Katy Prairie Conservancy

This project seeks to transform an existing Katy Prairie Conservancy field office/ storage shed into an education center. The architects paired down its exterior sheathing and structure to bare necessities. The entry breezeway bisecting the building is scaled to provide shelter and shade for outdoor educational venues while serving as an exterior corridor for the native seed nursery to the south. Visitors sequence into the primary hall where the horizontality of the prairie is heightened and re-presented through the framework of the building. Small learning pods are dispersed throughout the main educational hall, enabling visitors to interact with informational media that interpret distinct subtleties of the prairie.

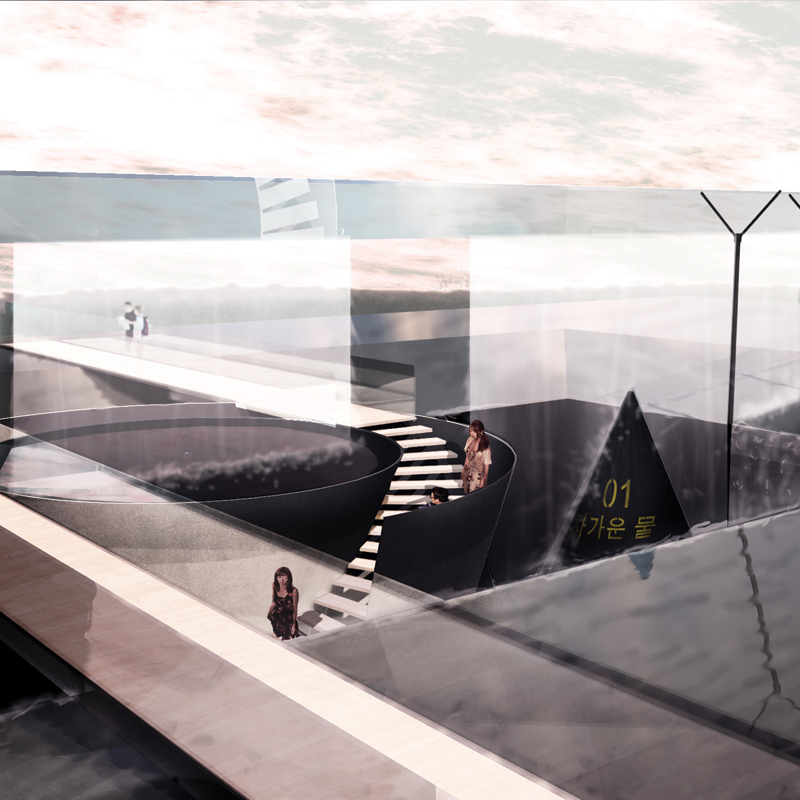

(C)ommunal Basin

The C-basin is a nondiscriminatory siphon that collects, disperses, and ultimately cumulates social activities and circumstances through its vertical section. It was completed for an Arch Out Loud open-ideas competition that requested underground bath house proposals for the Korean Demilitarized Zone. DMZ border fence posts are re-appropriated as wayfinding markers to the basin and structure for dispensing water. The varying pool funnels offer distinct sensory experiences. Bath house programs are seen as opportunities for conversation and contemplation mediated by water. The architects used the proposal to test latent potentials of the sub-terrain, dualities of the “wall and ground plane,” and re-appropriation (subverting the “Y” fence posts as sponsors of mediation instead of elements for division).