In Conversation with AIA Gold Medal Winners David Lake and Ted Flato

Texas Architect writer James Russell recently spoke with AIA Gold Medal recipients David Lake, FAIA, and Ted Flato, FAIA, about how their architectural philosophy and design approach has developed over their more than four decades of practice.

—

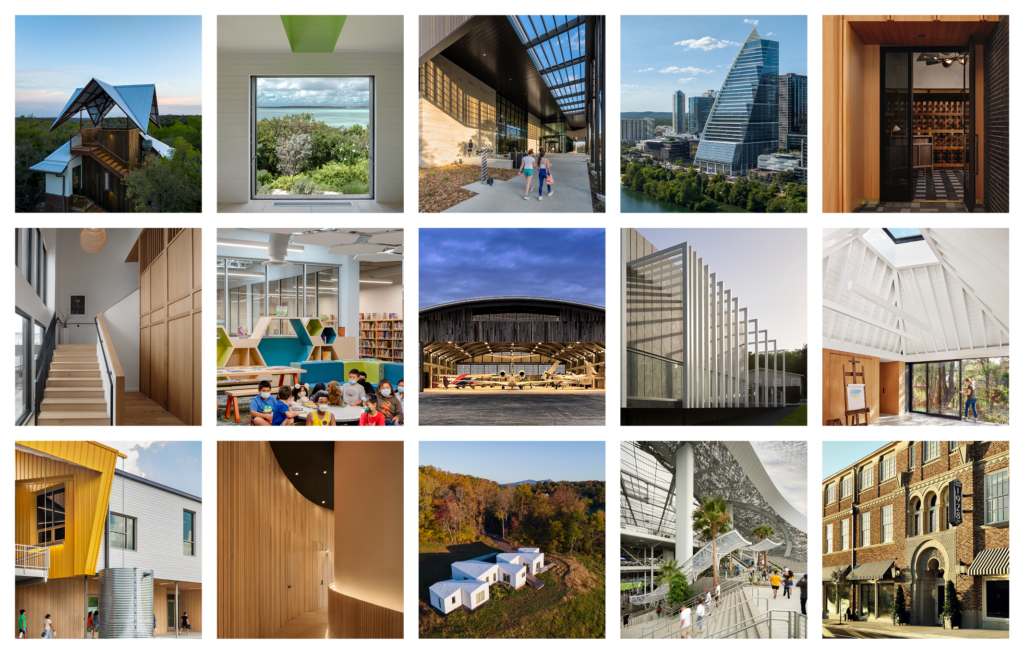

In his 50-year career, David Lake has carved a unique path dedicated to the belief that design, development, urban advocacy, and environmentalism must merge if we are to address climate change and help heal and sustain our planet. With a passion for sustainable urban development, Lake leads Lake|Flato’s urban studio.

—

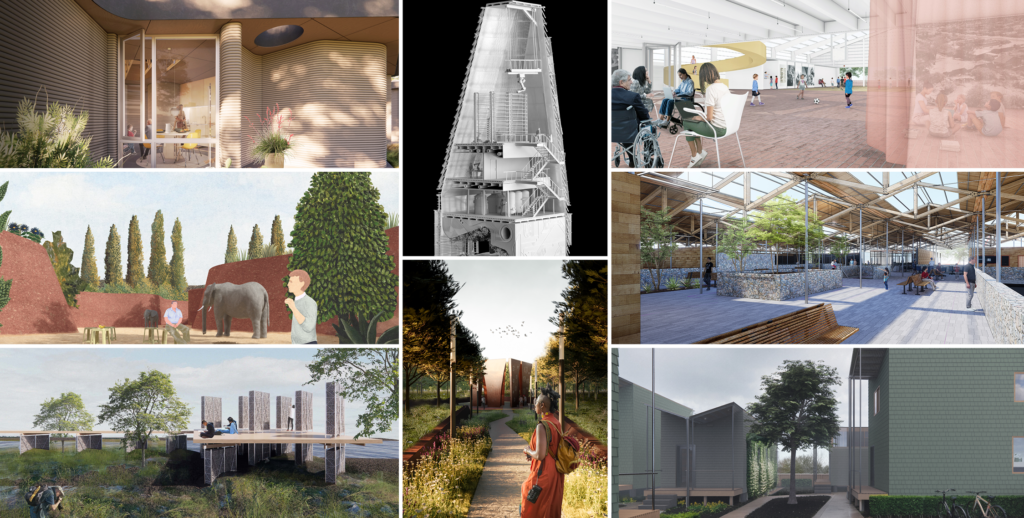

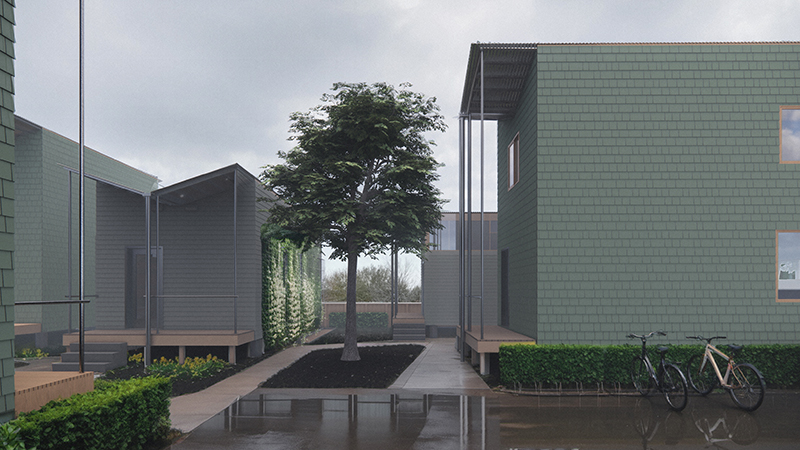

Ted Flato has received critical acclaim for his straightforward regional designs, which incorporate indigenous building forms and materials and respond to the context of their unique landscapes. Flato seeks to conserve energy and natural resources while creating healthy built environments. His interest in a myriad of building systems has resulted in projects focused on mass timber, prefabrication, and 3D printing, among others.

James Russell: You were mentored by the indelible San Antonio architect-activist O’Neil Ford. How did working for him influence your practice? How do you differ?

Ted Flato, FAIA: O’Neil was a great mentor whose uniquely practical approach to modernism was a wonderful counterpoint to the architectural thinking—postmodernism—of the time. And he brought David and me together. He saw it as an interesting experiment, to put two very strong, opinionated people together and watch the sparks fly. It ultimately created an amazing friendship.

Having grown up hiking, sailing, and camping in Texas, we cared deeply about Texas’s environment. So, when we started our firm, we were able to leverage that appreciation and knowledge of the outdoors with the lessons learned from O’Neil and put our own spin on it. It allowed us to grow our firm and hone our philosophy: that our architecture ought to be molded by the environment.

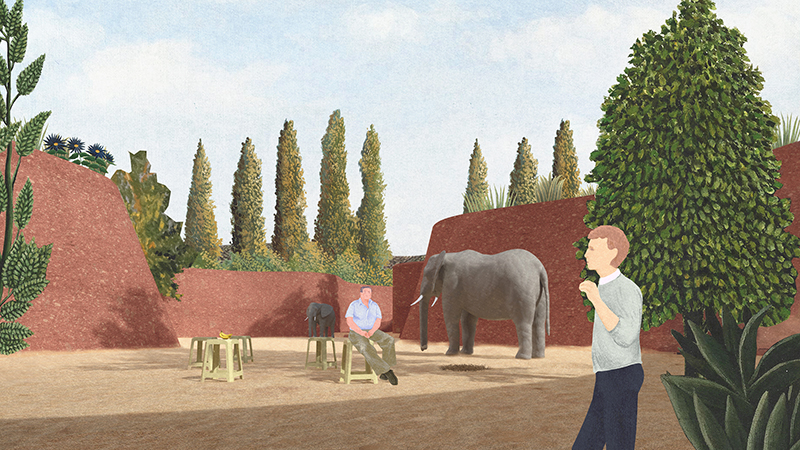

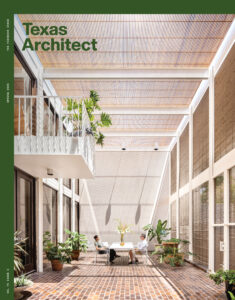

As an example, at Trinity University (one of Ford’s best projects), we recently rehabilitated two great midcentury buildings and added a new building to create a humanities quadrangle. The new building allowed us to complete a courtyard around some existing gnarly oaks, as well as to introduce a new structural system, mass timber, which O’Neil would have loved. It is sustainable; it’s structural; it’s beautiful. What a full-circle opportunity for us. It was a fun time for us to remember our fond memories of O’Neil exactly 40 years ago.

JR: Ford was known for shaping the discourse of regional architecture, his imprint on San Antonio, and his activism. As a firm based in San Antonio and Texas, do you feel you are carrying that distinct legacy? How do you translate that experience in San Antonio to other places with contentious spaces?

TF: We are passionate about the built environment. Often that means designing buildings; sometimes that means being an advocate.

David Lake, FAIA: We share the idea of the architect as a citizen architect, as somebody who really is thinking and moving beyond just the immediate projects at hand. One of the reasons we have been successful is because we started in San Antonio and made a difference. We saw what O’Neil and his wife, Wanda, were able to do during their fights to keep San Antonio’s culture and historic legacy intact. We saw how effective they were at choosing the right battles and fighting them no matter what the circumstances were.

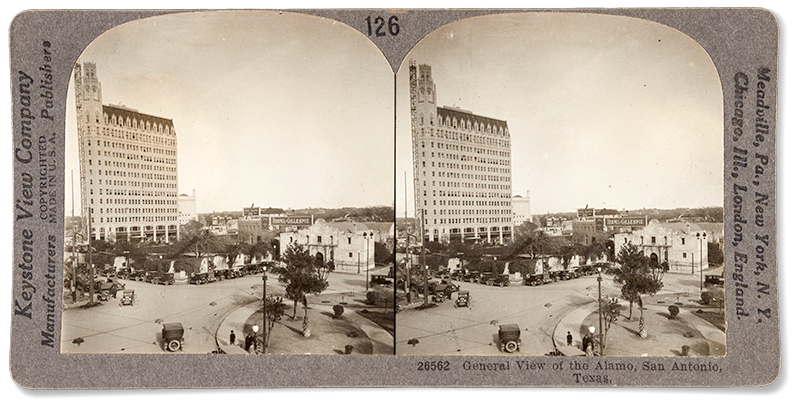

Most recently, Ted and I brought together developers and architects to stop the state of Texas from building a wall around the Alamo and disrupting Alamo Plaza. We aligned with several architecture firms to keep Alamo Plaza open as one of our state’s most important urban spaces.

The state hoped to build gates and charge admission, and to destroy parts of our built heritage. The Woolworth Building, [which had] one of the first desegrated lunch counters in Texas, was supposed to be demolished. We all said: “Don’t wall our citizens out. Do not destroy forever our urban and historic authenticity.”

We’ve had opportunities to both energize civic spaces and connect urban cores to nature. In San Antonio, we extended the Pearl District to the river, with the incredible developer Silver Ventures and Oxbow Development. We’ve now created an urban forest of a thousand trees, all watered by water coming off the roofs. Conservation of resources undergirds our passion for the built environment and communicating these ideals in order to craft community. We don’t mind wading in and having to fight if we feel like our city’s character or open spaces are at risk.

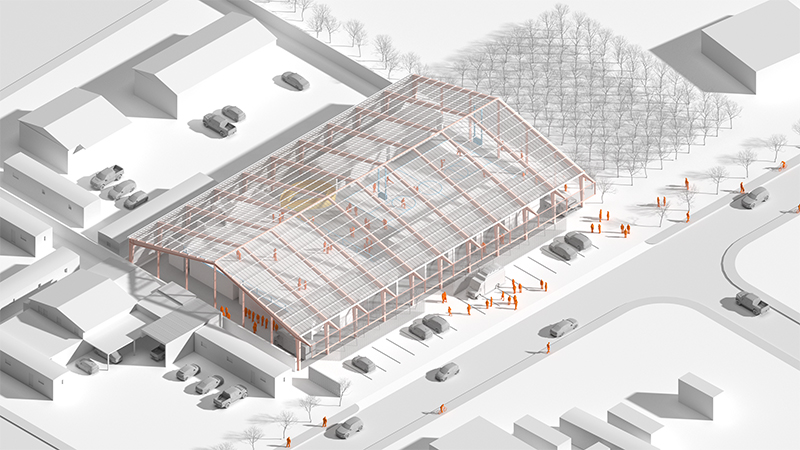

We apply science to high-performance buildings, moving beyond regional passive response to climate to looking at all building systems, the resources that go into them, and striving for excellence throughout the entire design, construction, and postoccupancy journey.

We also do not shy away from pushing hard, and that’s why it’s in our DNA. I think one of the reasons we were honored with the [AIA] Gold Medal is that we’ve received 16 [AIA] Committee on the Environment Top Ten awards—more than any other firm. And it’s because we, as a firm, have a very rigorous, integrated design process.

Each project starts with a sustainability charrette led by Heather Holdridge, [Assoc. AIA,] our director of design performance and partner who’s in charge of sustainability. We bring together the design team, the owner, the users, and concerned citizens—whoever we think will yield ideas. On the Austin Central Library, we had more than 150 people in the charrette. Originally the City of Austin wanted a LEED-certified library. But we pushed. In our very first meeting with the city, we said: “We want it to be LEED Platinum. We want it to be the best daylit library in the United States, and we want it to be Austin’s living room.” We set metrics at that first charrette: What kind of energy reduction will it have? What will the resource reduction be? We used the LEED metrics to set quantifiable goals. We were checking the photometrics from the skylight and from all the different perimeter light sources to confirm that our assumptions were correct.

JR: As you said, you are passionate about the built environment. How do you distinguish architecture from the built environment?

DL: One of our greatest accomplishments is conserving 85,000 acres across the country and preserving different species in those unique habitats. We know the value of providing open space, connecting to the outdoors, and nurturing all life. It’s not, “I’m going to design a cool looking building.” It’s a broader ideal that informs our role as architects to conserve all life and return us to a state of balance with nature.

We don’t see ourselves as necessarily fashion-forward sculptors at all. We see ourselves as caring about applying a rigor to a process that leads to beautiful buildings. Don’t get me wrong; we love architecture. We love beautiful details, and we care deeply about materials. But we care most about comfort.

It is pivotal that people understand architecture, that it seems practical and purposeful and welcoming, and that when you’re in our buildings, your creativity and productivity go up and you’re happier.

And that’s what gives us joy. Whether we’re doing an arena for the San Antonio Spurs or the Austin Central Library or Trinity University, we just care about pushing forward this idea of high-performance buildings that are truly rooted in place.

TF: We’re in the state of Texas, and it isn’t a hotbed of environmentalism. That has allowed us to hone our particular approach to practical, proven sustainability. It’s the idea that we are trying to create clients who advocate for sustainability, so that they are also talking about it and proud of it. Having that knowledge about how their buildings function or save operational costs is ultimately what gets them excited. After that, it’s throwing a small rock in a pond, and you’re trying to create ripple effects. Some of those ripples come from client advocates, but some of them also come from fellow architects who recognize what we’re doing, and they can see, “Oh, I could do that; that’s reasonably affordable and isn’t over the top.”

That is what we would call practical adaptable sustainability. The world is looking to our profession at this moment, at this critical moment of climate change, for real leadership. It requires all of us to be moving in the same direction.

Where we began, with ranching clients who wanted practical and simple projects connected to the environment, gave us a good foundation that then later informed the way we do really large sustainable projects. We leverage the outdoors and then apply science and other kinds of smart systems.

There’s also the perfect project: the Living Building-certified visitor center for the Dixon Water Foundation. We could see from the very beginning that it could be an unconditioned experience and that it was going to be a very sustainable building and reinforce their message around environmental stewardship. But we went further and asked: “What do you think of actually pushing the envelope and doing this thing that no one has done except on the East Coast and West Coast—this idea of a Living Building?” And they embraced it. But again, now you’re asking your client what do they think? They’re part of it; they become really proud of it. They become advocates for it. That’s what you want. It’s like David was saying on the library, they were willing to settle for one level, but if you engage them and ask them more questions and keep it deliberate, sometimes you can find yourself in a whole new place.

JR: What do you then say to younger architects or those in training? They’re dealing with everything from high amounts of debt to climate violence to resource scarcity. Y’all aren’t ones to say, “Give up.”

TF: We’re very lucky that we have an office of 150 people. It allows you to have a lot of different projects and project types. When we started our office, we were small, just the two of us and a couple of others, and our design process was rooted in collaboration. David and I had to work together.

Our process is not centered around a sole genius. Instead, it is a group of people working together toward a single goal of connecting to the environment. It is something that younger architects and clients can easily embrace. We have amazing talent in our firm, with younger and spirited architects showing up all the time because they appreciate the direction of the architecture, our commitment. They are very talented designers on their own, and they want that agency to push things beyond what we do. The exciting part of what we’re doing is watching the work continue to evolve and stay consistent. It’s encouraging to see those younger architects continue to push us and move the work forward.

DL: The smartest thing we did was recognize when we have incredibly wise, driven people who are like us, to give them plenty of space to go do their thing. And we trust them. I think trust is everything in architecture. You have to trust and empower the people around you. You’ve got to really trust the process.

JR: Given that your firm is rooted in people and place, how do you stay so optimistic? And what’s next?

DL: We’re both incredibly honored and lucky to love what we do. That’s what brought us together in this enterprise 40 years ago. It’s what drives us forward. We are honored to be architects. We see our role as moving beyond sheltering humankind to sheltering all species, all life, and all ecosystems. And that’s what leads us back to help healing our natural realm and returning balance with the environment. We used to be in balance. We must lead by example and balance art with science to craft sustainable communities for all.

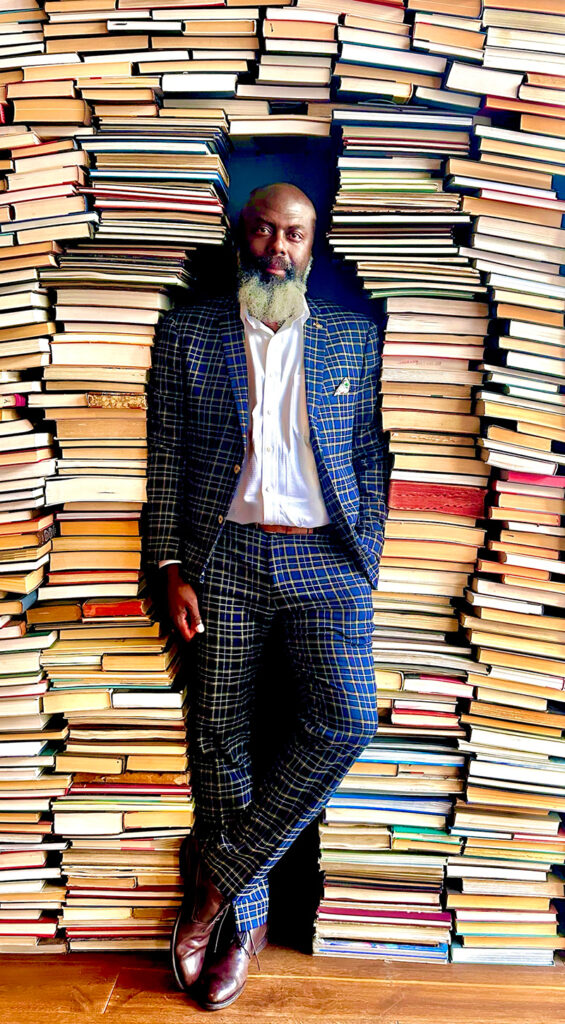

James Russell is a journalist in Fort Worth writing about art, the built environment, and politics. His writing has appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine, CityLab, Arts and Culture Texas, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, among others.

James Russell is a journalist in Fort Worth writing about art, the built environment, and politics. His writing has appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine, CityLab, Arts and Culture Texas, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, among others.

Also from this issue