Texas Roots, Houston’s Growth

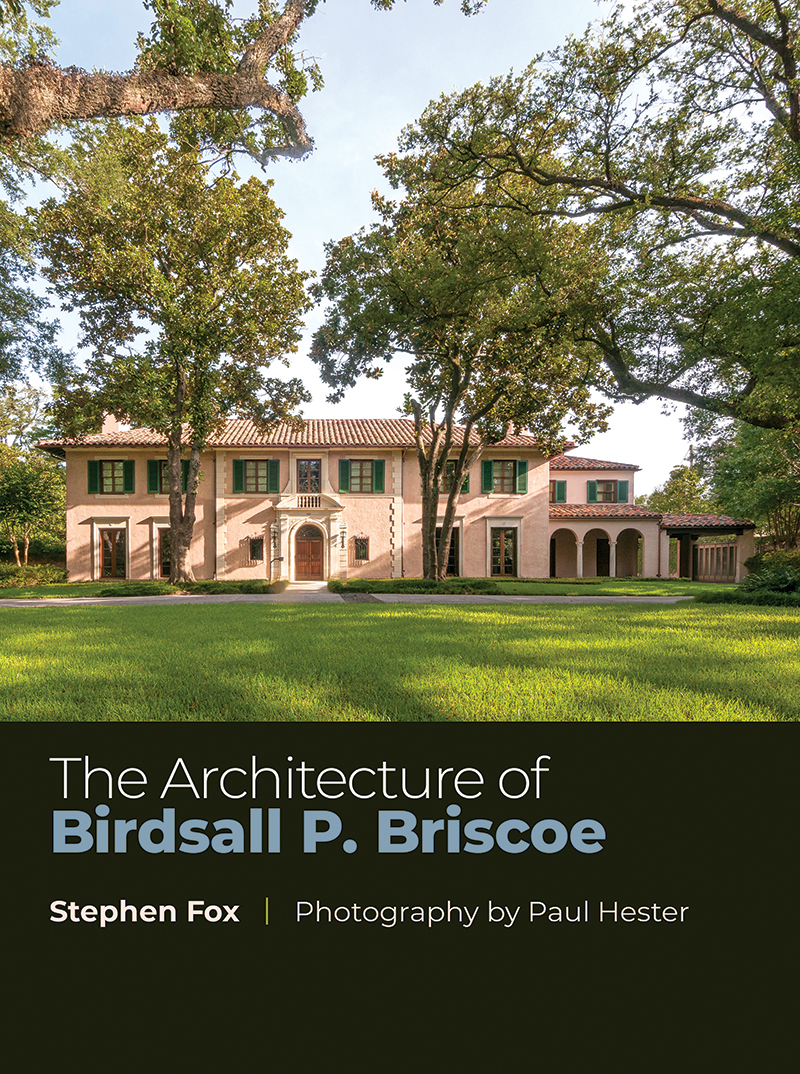

The Architecture of Birdsall P. Briscoe

Stephen Fox

Texas A&M University Press, 2022

The Architecture of Birdsall P. Briscoe” is the second book by author Stephen Fox to be published in the “Sara and John Lindsey Series in the Arts and Humanities” by Texas A&M University Press. His first book in this series was “The County Houses of John T. Staub,” which details the life of another Houstonian architect of the same era. Fox is a renowned and often-studied historian of Texas architecture who takes a specific interest in the city of Houston. He teaches at Rice University and the University of Houston in their respective schools of architecture, and it is evident from his topics of interest that his Houston roots run deep.

The book covers the life and work of Birdsall P. Briscoe, an architect practicing in Houston from the turn of the 20th century until the mid-1950s. A “Southern gentleman architect,” Briscoe was born into a strong Texas heritage. Many of his family members were founders of Texas and part of the early “elite” class within the newly formed Republic of Texas. And so Briscoe began his career with societal clout in tow. He was not formally trained as an architect, although he had attended both Texas A&M University and the University of Texas; Briscoe learned his craft under the apprenticeship model, working for a few architects in Houston in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He eventually stepped out on his own, partnering with other Houstonian architects during his early career.

Briscoe’s career was first interrupted by World War I and then suffered through the Great Depression. As noted in the book, the architect used his social standing to work for some of Houston’s most influential residents and socialites. He designed homes for family friends and acquaintances, as well as their extended families, establishing an extensive network of related clients and projects over time. While Briscoe also completed commercial, institutional, and civic projects during his lifetime, his residential work was most prevalent and contributed most to his legacy.

The book frames these homes as “country residences,” a trend among the upper-class citizens of the era. Many of the houses still exist in areas like River Oaks, Shadyside, and Riverside Terrace and are occupied by some of Houston’s more affluent residents. Briscoe’s work was elegant and drew from multiple historical styles, attempting to create a new sense of society by rejecting some of the current trends in elitist residential designs of the times. His early works explored “prairie”- and “craftsman”-style residences in an attempt to diverge from the trends of Victorian and Colonial Revival architecture. The residences evolved into the “country house” typology, which borrowed elements from the villas of Italy and the Mediterranean, reduced ornamentation, and reoriented the house. His peers described his work as very responsive to the needs of his patrons.

Most of Briscoe’s surviving work is located in River Oaks, which was developed by the famous Hogg family of Texas. Briscoe was already a prominent architect by the time the development began in the late 1920s and had previously completed work for the Hogg family. He designed homes for many patrons in the new development, and today the neighborhood boasts over 30 existing houses by Briscoe. Three have been designated as City of Houston Landmarks, and one — The Clayton House — is on the National Register of Historic Places. The book focuses on the ideas of style, taste, and fashion as they relate to Briscoe’s ability to create social capital and craft a new image for Houston and its upper-class citizens. The book leans toward the notion that through his work, Briscoe was able to de-emphasize the traditional residential architectural trends of the time and establish a new identity for the city’s prominent citizens.

More a treatise on Houston’s early development than an architectural monograph, the book is a dense read and contains more text than do typical architectural coffee table books. The photos by Paul Hester showcase Briscoe’s work in glorious fashion, and the historical images included provide insight into the societal ideologies and social conditions during Briscoe’s career. However, there are few drawings within the more than 350 pages of the book, and at times, it is difficult to fully comprehend the design achievements of the architect, as plan layouts are described in words without graphic references. While there may be various reasons for this omission, some additional images, even if reproductions, could aid in comprehension and clarification of the residential designs. The lack of architectural graphics does not detract from the book’s quality, but it does skew the publication more in the direction of a historical piece than an architectural monograph.

Briscoe certainly worked within a very exclusive network of prominent early Texans, and the people, relationships, places, and businesses discussed were all fundamental to the development of Houston. This book is an excellent source for readers seeking to learn more about the history and development of Texas and Houston during the first 50 years of the 20th century as well as those interested in learning about Briscoe’s life and work. Fox has captured the architecture and its motivations while remaining apolitical in his delivery of the politics, exclusions, and social constructs of this elite community. The significance of this decision is ultimately left for the reader to determine.

Andrew Hawkins, AIA, is principal of Hawkins Architecture in College Station and an assistant professor of practice in the architecture department at Texas A&M University.

Also from this issue