There Will Come Soft Rains

The Theresa Passive House in Austin is a case study in single-family sustainability.

Client Farmer Family

Architects Forge Craft Architecture + Design &

Hugh Jefferson Randolph Architects

Interior Design Studio Ferme

Contractor CleanTag

Structural Engineer Lester Jay Germanio

MEP Engineer Positive Energy

Commissioning Consultants Positive Energy, ATS

HVAC Installer New Results

Solar & Battery Backup Installer Freedom Solar

Landscape Architect Austin Outdoor Design

Irrigation Wilson Irrigation

Millwork Lavish for Home

In Ray Bradbury’s 1950 short story “There Will Come Soft Rains,” a lone house stands at the edge of a destroyed settlement. Without its nuclear family of occupants, the house tools along, offering the comforts of home: automatically whipping up breakfast, watering the prickly lawn, and opening the garage door for a commute that will never come.

Eventually, the house combusts and shudders to ashes, despite being equipped with firehoses and an alarm system. Bradbury aimed his critique at nuclear escalation, but its predictions, set in the year 2026, feel prescient today.

In a landscape of floods, fires, droughts, heat, and freezes, Bradbury’s questions of technology, architecture, and culture ring true. Will technology be fast and powerful enough to help turn the tide on climate change? How can our buildings weather a changing, more dangerous climate? Can we retrofit the single-family lifestyle for an energy-scarce future?

The Theresa Passive House in the Clarksville neighborhood of Austin is an architectural answer to this line of questioning. The renovated Craftsman bungalow was designed by the husband-and-wife owners — Trey Farmer, AIA, of Forge Craft Architecture + Design, and Adrienne Farmer of interior design outfit Studio Ferme — to bring a radical approach to sustainable building.

The highest-scoring project to date in the Austin Energy Green Building program, the Farmers’ house was designed to achieve passive certification through the Passive House Institute US (PHIUS), a nonprofit advocating for the adoption of high-performance passive building. Focused on a rigorous level of energy efficiency while offering wellness benefits, Passive House standards were developed in Europe and popularized in cooler North American climates. The introduction of the PHIUS+ 2015 building standard enabled certified passive projects to be feasible in hot, humid climates like Texas’.

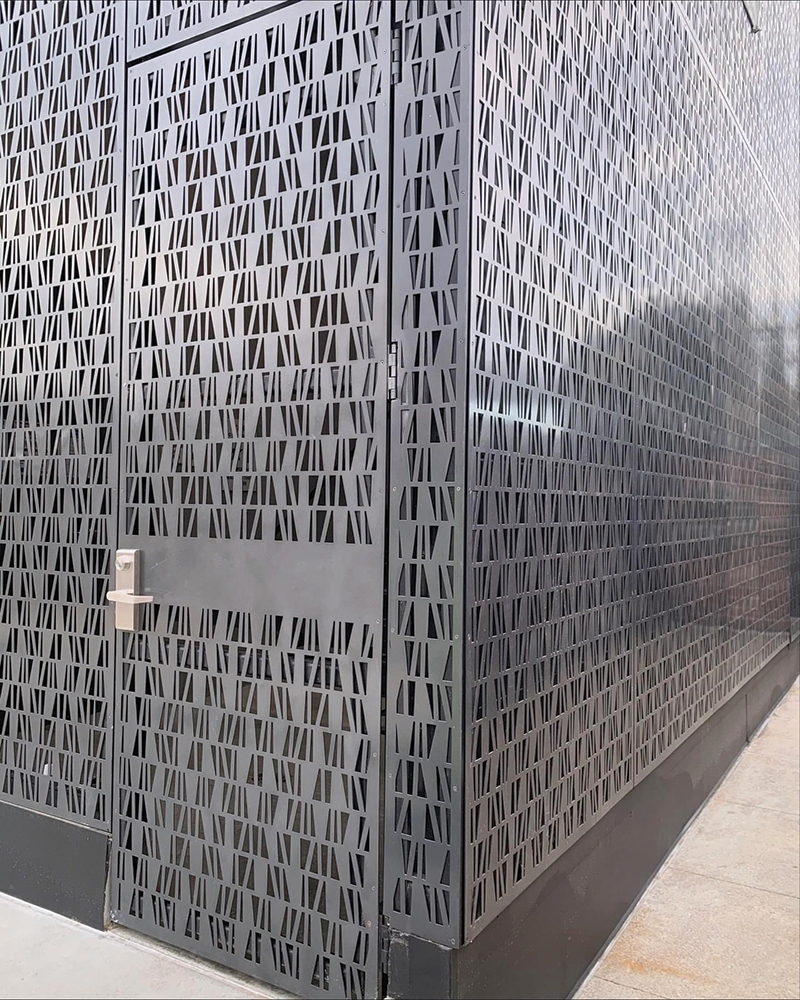

When we visited the Theresa Passive House, the sounds of the MoPac Expressway, a mere 500 yards away, quickly dissipated. There was something futuristic about the house, even though its footprint was some hundred years old. Following Farmer, with his fluffy dog and toddler in tow, we padded down an entryway that was clad in a warm cognac shiplap. The hallway opened into a spacious kitchen, centrally lit under a glowing lightwell, and a living area with sweeping views of downtown Austin.

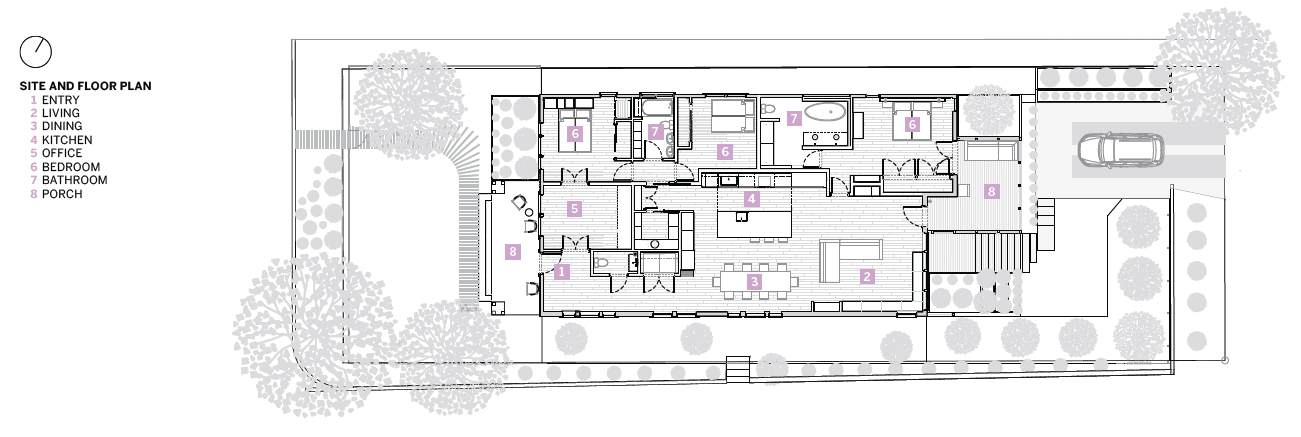

While working on the design, the team balanced the desire to preserve the 1914 bungalow with the strictures of the Passive House specifications. Ultimately, the house retained the layout of the Craftsman house along with a more recent addition of a primary suite and screened-in porch, but the entire structure was rebuilt from the frame up. Studs from the historic frame, which wouldn’t have been up to PHIUS performance standards, were repurposed for the entryway shiplap.

On the old west end of the house are two small bedrooms, a full bathroom with two decorative sinks, and a small office. In the corner room, we climbed up a wooden ladder into a lofted room. There, behind an innocuous door amongst luggage and cardboard boxes, was the workhorse that makes much of the Theresa Passive House possible: an environmental control system consisting of a heat pump hot water heater, a VRF heat pump AC unit, a dedicated dehumidifier, a hospital grade filtration system, and an energy recovery ventilator.

Standing in the loft alongside the mechanical heart of the house, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the sci-fi future Bradbury had imagined, where machines within a high-performance building perform the minutest of details of daily life. But as Farmer walked us through the project, I was struck by the simplicity of the elements that helped ensure such a dramatic reduction in energy usage. Insulation is moved up to the roofline to avoid mold and temperature change in the attic; windows are triple-glazed; overhangs are used to shade large windows; and building transitions are simplified to decrease temperature or moisture exchange. Combined with the HVAC system, the strategic use of specialized building materials and these design and construction choices deliver energy savings that make the Theresa Passive House a nearly net zero project.

As Texas’ third certified Passive House, the home was an experiment in more ways than one. Farmer emphasized that he hoped the Theresa Passive House would be a proof point for Passive House building, normalizing the approach for both the design community and end users. And in just the first two years of its existence, the Theresa Passive House has been put to the test.

The Farmers moved in just before the pandemic began in 2020. Luckily, an additional benefit of passive building strategies is exceptional indoor air quality. With an extremely airtight enclosure, the ERV system delivers fresh air throughout the house. The Farmers have a hospital-grade filter as part of the ERV, a boon during a respiratory-borne pandemic as well as in a region known for its allergen-rich winds.

The family also weathered Winter Storm Uri in the Theresa Passive House. While many of the historic homes in the neighborhood suffered from burst pipes and extremely cold temperatures, the Farmers’ bottomed out at around 47 degrees after three days of single-digit weather before the power was restored. Likewise, UT Austin researchers looked into the Theresa Passive House’s ability to tolerate heat. It was compared to a house on the campus of the JJ Pickle Research Center built to city of Austin code standards. After 12 hours on a sweltering summer day, the temperature in the code house was 98 degrees, while the Passive House registered 83 degrees.

These resiliency benefits are good for buildings, but they’re also good for people. In dangerous weather conditions, the more stable the temperature of a house, the better for its inhabitants. In particular, this cushion of time it takes for indoor temperatures to rise or fall gives children, older adults, or people with conditions that make it harder to regulate body temperature a better chance of riding out a power outage or severe weather pattern safely.

The Farmers’ house is the nucleus of a nascent Passive House movement in Austin. During construction, the couple hosted events for companies that make products used in this type of building. They also welcome UT Austin students to visit and share data and designs openly as a case study. And in his work on Forge Craft Architecture’s affordable housing projects, Farmer is bringing Passive House to multifamily buildings, making these crucial resiliency benefits available to even more communities who need it.

The day we spoke was just a few weeks after the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. With its generous subsidies for heat pumps, especially for middle- and low-income families, as well as other benefits for energy-efficient building, a more resilient future could be on the horizon.

Penny Snyder is an arts communicator and public policy graduate student in Austin.

For more on how the Theresa Passive House achieved PHIUS certification and exceeded targets within three of the framework’s categories — Energy, Change, and Discovery — see “Lessons in Sustainable Design from the Theresa Passive House.”

Also from this issue