Out of Office

Office and retail design are reconsidered on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Just as cholera outbreaks in the 19th century led to redesigned sewer systems and the 1918 flu pandemic spurred the development of wellness-focused, modernist schools of thought like Bauhaus, the COVID-19 pandemic has radically accelerated, or altered entirely, design thinking in many disciplines. Perhaps the most obvious impacts can be felt in the office and hospitality industries, where vacancy rates have risen steadily, impacted by a radical shift in where and how people conduct business.

The U.S. Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes recently showed that the percent of full days spent working from home has stabilized at 30 percent. That includes the 15 percent of workers who remain full-time remote, as well as the 30 percent of workers in hybrid roles. Their results also show that employers plan for employees to spend an average of 2.4 days per week working from home, and that number is in fact rising.

In August 2022, vacancy rates for office space in Austin stood at 18 percent, higher than the national average (which reports put between 15 and 17 percent). Pre-pandemic, the national office vacancy rate was 9 percent. As we navigate the continuing shockwaves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ripple effects are being felt in spaces both public and private. The initial shift to remote work, naively expected to last only a few weeks, has caused a seismic shift in the way we interact with the built environment. Workers in many white-collar fields adjusted quickly to these changes, carving out space in their bedrooms or closets and crafting new routines that often left them wondering if they really needed to go in to an office. Still, real estate development of new office space has continued apace, with the U.S. adding more than 50 million square feet of office space in 2021 and on track to repeat that figure in 2022 per commercial real estate firm JLL.

As with any systemic change, the backlash arrived, with companies like Google attempting to move more of their workforce back to the office and pundits like Malcolm Gladwell opining about the necessity of in-office collaboration and performance. On the “Diary of a CEO” podcast, Gladwell asked: “If you’re just sitting in your pajamas in your bedroom, is that the work life you want to live? … What have you reduced your life to?”

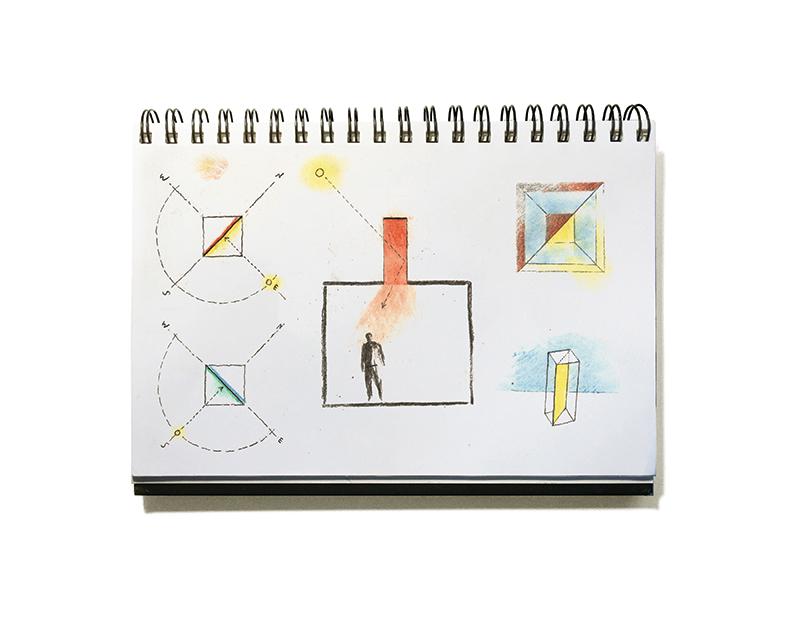

Architects are caught in the middle of this culture war, working to design office spaces conducive to collaboration that provide value to employees who are able to accomplish the majority of their tasks from home, and to provide the features that employers believe will entice a reluctant workforce back into routines that no longer fit: Long commutes, business casual dress codes, and open office spaces that provide little comfort or privacy have begun to feel like relics of a distant past.

In Austin, Google’s new headquarters topped out in July 2021. The Pelli Clarke & Partners design sits prominently, like a ship with unfurling sails, on Lady Bird Lake in the city’s ever-expanding downtown core. At the time, plans for the future were in a state of flux, with vaccines recently rolled out to all who wanted them — perhaps offices would soon be full again, the world neatly returned to its pre-pandemic state. But then came Delta, and Omicron, and when employees finally returned to their mandated days in the office, they were often greeted by emptiness. It is unfair to blame this emptiness entirely on the design and utility of offices; successive waves of new variants have made safety a continuing concern for many employees, and their reticence is logical.

As employers move toward hybrid models, in which workers split their time between the office and home, one of the challenges to contend with is the unknown. When employees can choose where to spend their time, spaces must be designed and planned for an undetermined, fluctuating number of people. Nena Martin, director of workplace at Gensler Austin and co-leader of the firm’s global technology workplace, pointed out the impact these uncertainties can have across all aspects of company culture. “When you have full kitchens, how do you know how many meals to make? It doesn’t help that the pandemic continues to ebb and flow and planning for the unknown presents new challenges.”

As a result, open office space trends may continue, with spaces designed for flexible arrangements instead of private offices or assigned desks. But as COVID exposure becomes less of a concern, it seems that there are two strategies to create offices that tempt workers back: make offices feel more like home, or make offices social hubs, providing the potential for the types of interaction that are impossible, or at the very least difficult, from home. “The days of really sterile office environments with cold, fluorescent lighting and powerful AC are over,” says Martin.

She sees the pandemic as having been an accelerant of existing office design trends rather than a disruptor. “We realized that, in order for folks to be in the office — to want to be part of a company’s culture — it’s really important to have dynamic spaces that are going to make people feel comfortable and give them a sense of purpose. It has to have the flexibility that we have had at home — from the option to sit in different areas and access to food to accommodate personal needs — you have to be able to translate that into the office space.”

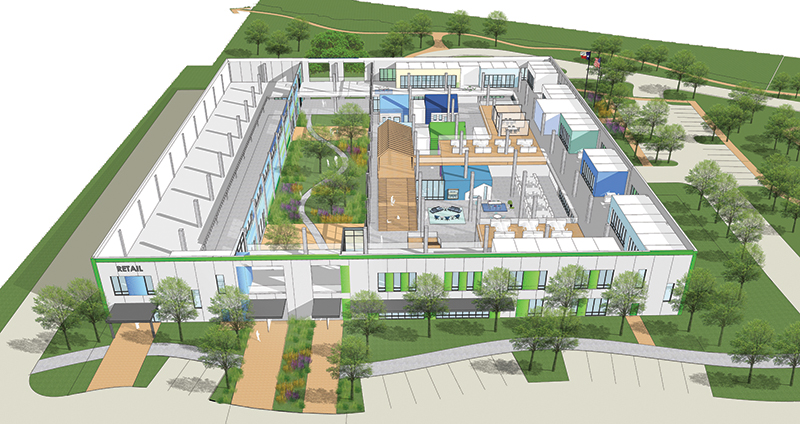

In addition to designing office spaces that feel like elegant hotel lobbies or bustling cafes — energetic touchpoints where people want to spend their time — Martin believes that another fundamental shift will be toward inviting the community into spaces that were previously more private.

“We’re seeing spaces that are being more focused towards the community, spaces that can be rented out for different types of events, especially on the first floor. Landlords are having to get clever — what do we do with these empty areas? — turning certain vacant areas into first-tier gyms or fitness centers or working lounge areas.”

The retail sector, which was facing the need for dramatic change even before the pandemic, is looking toward similar changes to invite customers back to shop in person instead of online. Vacancy rates across all types of retail establishments sit at 5.1 percent, with mall retail higher, at 6.9 percent; neighborhood center retail at 7.9 percent; and general retail at 3.2 percent. Pre-pandemic, the overall vacancy rate had already begun to rise, hitting 4.7 percent in late 2019. But demand has remained fairly steady for industrial retail space. The growth of e-commerce has offset the deflation of in-person shopping, and online retailers still need space for warehousing and storage. Much like in the office sector, conditions are still shifting, and changes in the economy and consumer behavior have made it difficult to predict future demand for retail space.

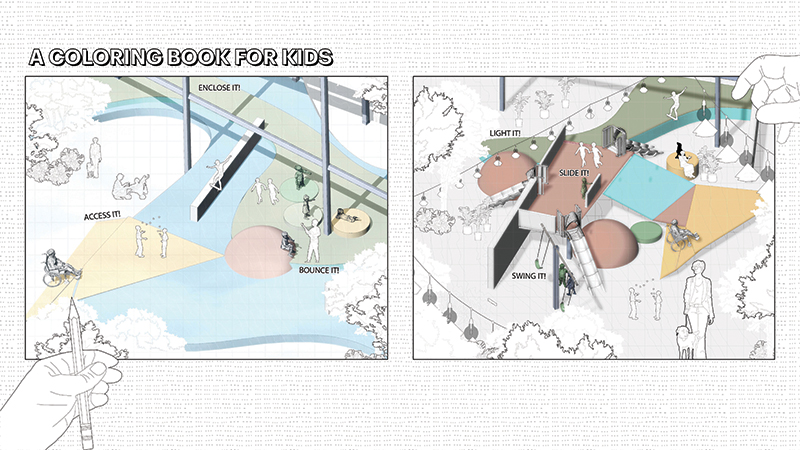

According to Dana Foley, design director at Gensler, e-commerce purchases are expected to continue to climb 160 percent over the coming years. Combined with the pandemic’s acceleration of such shopping behaviors as curbside pickup, this means that retail spaces, from mixed-use to mall, are also looking for new ways to bring the community inside. “People aren’t just going to the store for retail — they can spread out, have access to outdoor spaces, shop in retail stores that are more experiential,” says Foley. “They’ve had to pivot from shoppers coming into the store on a day-to-day basis.”

Outdoor space has become such a priority that development companies have taken to turning traditional malls “inside out” — taking the roof off central courtyards and atriums to create porches and breezeways.

They’re also inviting local artisans to sell homegrown products to signal that these spaces are invested in community. While they are bringing in new retailers, they’re also finding new places to sell goods, converting public spaces of all stripes into mini-malls. Foley says: “Retail clients are trying to move those retail items forward in lifestyle locations — business, leisure, and hotels — because they may be selling things like local coffee and handcrafted items. They’re trying to create something that doesn’t look like a flea market, but that’s purposely designed. Because of the way people are working and living, they’re bringing a lot of these things together as a hybrid mixture so that you aren’t going more places and being more exposed.”

This expanded notion of the one-stop shop could apply to offices, too, as the lines between the types of public spaces blur. “[We’re] creating a change in our environment that is welcoming people back into these spaces to connect,” says Foley. “We were created for community. I think we’re designing with those values now.”

But perhaps the things that benefit communities most aren’t gathering spaces or open-air malls; maybe they’re slightly less glamorous. Improvements to indoor air-quality systems are already underway in many buildings, both retail and office alike. With the lingering specter of COVID-19, the average person is more aware of the ways ventilation can affect their health than they were two or three years ago.

“With the pandemic, people have become more sensitive and aware,” Martin says. “When someone is sneezing, where are the air particles going? What type of filtering system are we using in new buildings? And how are we retrofitting HVAC in existing buildings?” She predicts that newer buildings will have lower vacancy rates because of their newer air filtration systems.

Another way to benefit communities? Make office spaces more sustainable. And not just from the outset — tenant turnover is a major contributor to waste. “We’re used to three-, five-, seven-year leases, and when there’s a change of tenant, all of that material goes into landfill,” says Martin. “We have to educate developers, landlords, and end-users to be mindful and use materials that are going to be long-lasting.” This could include a shift from carpeted offices to designs that use recycled wood flooring instead, a durable material that can last between tenants. Doors and paint are other major culprits.

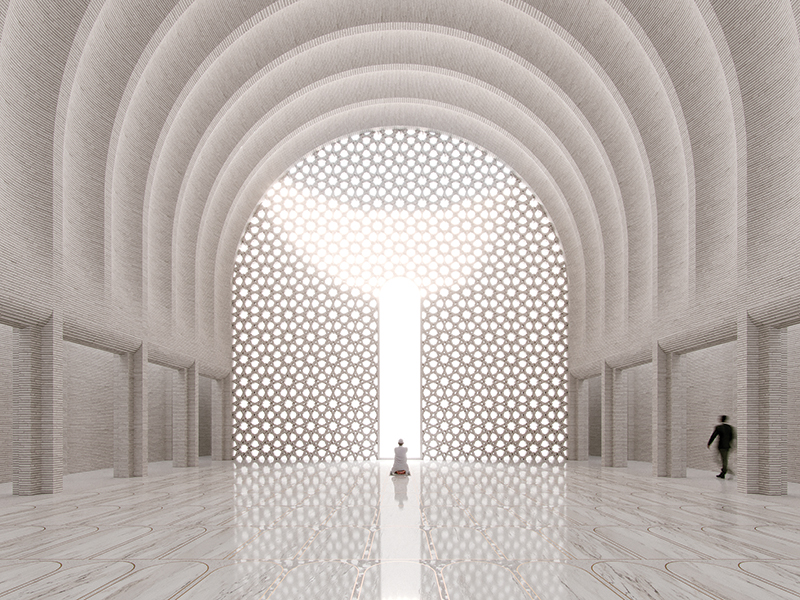

This would necessitate a shift in thinking, from designing offices built for current trends and meant for tenants to improve and improve again, to building spaces that are intended to last for hundreds of years, with the flexibility to support all kinds of tenants without needing more than very minor changes. A focus on meeting basic human needs through design, rather than following trends, could lead to radical change in public space over the next several years, with buildings designed for public health and well-being, both on a global scale to fight climate change and on an individual scale, to help people connect safely with their neighbors.

What could this look like for offices? Martin says: “The future of workplace is one where there is a sense of purpose, a gathering place where one can collaborate, learn, and be productive. The office of the future needs to be adaptable, flexible, and able to accommodate neurodiversity. We need to think of the future of work as an extension of the natural environment with the complete cycle of life: Everything is interconnected.”

Perhaps this desire for radically re-envisioned spaces will help develop the next Le Corbusier or Adolf Loos, devising new frameworks for a post-COVID age that has yet to emerge. Or maybe we’ll all just be a little more comfortable in offices with gentle lighting and warmer temperatures. Either way, there isn’t a time machine to bring back the work environment of 2019, where employees were content to commute every day to spaces that weren’t necessarily designed to serve their needs. In order to fill these vacancies, creative, adaptable thinking will be required.

Alyssa Morris is a freelance writer based in Austin.

Also from this issue