In 2001, Boeing moved its headquarters to Chicago, in large part due to the city’s vibrant downtown, something the runner-up location, Dallas, could not, under any pretense, claim to have at the time. Losing the Boeing deal jump-started efforts to make the city’s downtown more attractive and dynamic, and the Downtown Parks Master Plan, created in 2004, identified potential locations for many future parks, several of which have since been created. Here, we examine the past, present, and future of three Dallas parks, including the approaches to their design and their impact on the urban environment.

Thanks-Giving Square

Completed in 1976, Thanks-Giving Square was one of the first parks in the heart of downtown Dallas. It was conceived as a contemplative space dedicated to bringing people together via “the common ground of gratitude.” As designed by Philip Johnson, these aims materialized as an inward-focused sunken garden, complete with 4-ft perimeter walls and a cascading water feature, both of which shut out the urban surroundings.

The square is open to the public, but the perimeter walls limit access to three points. On an average day, few people can be found within the square’s walls. In recent years, as downtown has gained more residents, the square’s green spaces have primarily been used as a destination for people to take out their dogs. It has also served as a civic gathering space, often after tragic events, but the aging, empty — and sometimes stinky — square is clearly not living up to its potential. Recognizing this, the Thanks-Giving Foundation has embarked on an effort with CallisonRTKL to update the space, both to improve its connection to its surroundings and to better fulfill the original mission.

The question of what those updates should be is a difficult one. The design team is working with the foundation on a proposal that balances reverence for Johnson’s vision while addressing the obvious drawbacks resulting from some of the design choices. The design framework seeks to preserve the vast majority of the elements while making the multi-level square more accessible to all potential users: An elevator is added at the location of the existing tunnel access; the bridge is replaced; and the outer wall is punctured in a few key locations to create more connectivity to the surroundings. At the western tip of the square (which is really a triangle) is a proposed new pavilion that will serve as an additional platform to support the foundation’s outward acts of giving. The space at grade and new connection point to the tunnels will open up more opportunities to engage with nonprofit organizations throughout the city.

While the team has focused on preserving the original vision and creating a “fresh start,” Johnson’s design creates constraints which may be difficult to overcome. Does creating a truly modern, open, welcoming, and usable space require sacrificing too much of the architect’s vision? Can we have a space that stays true to the original design, or does real activation warrant a more modern approach? Which vision should be prioritized?

Klyde Warren Park

Klyde Warren Park, Dallas’ freeway-topping jewel which has been successful beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, set a new tone for public space in Dallas. It demonstrated the need for public spaces in the urban core, and the resulting property value, development, and tax revenue explosion was immense. As park co-founder and chairman Jody Grant recalls, Klyde Warren was originally conceived as an economic development project, but it has become so much more. The 5.2-acre park contains a great lawn, a children’s play area, a restaurant, a performance pavilion, splash pads, a reading room, games for rent, a putting green, ping pong tables, natural planting areas, and a dog park. Despite so much programming, there is still space for people to simply sit in the shade and watch the activity. The designers struck a balance between ‘active’ and ‘passive’ that seems to be working quite well. One of the most passive areas is the far east end of the park, where a triangular section of lawn is bounded by two paths and Pearl Street. Here, the park design called for a fountain, but it was not included in the original build-out due to cost.

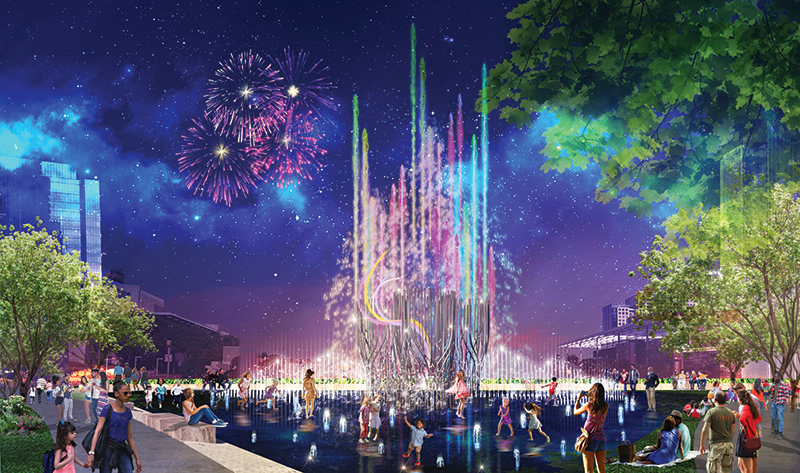

The park foundation recently announced a new planned fountain for this location — and it did so with an exceedingly fanciful rendering: giant illuminated shafts of rainbow-colored water jets shooting high into a night sky featuring a vivid Milky Way galaxy and fireworks exploding in the distance. Grant now realizes the tacky rendering was counterproductive — Dallas Morning News architecture critic Mark Lamster said it gave one “that feeling of mortification when you witness someone do something foolish.” Subsequent images, which display the fountain in a less embellished manner, show something much more appropriately scaled and devoid of gimmicks. Grant envisions the fountain as the entrance to the heart of the city and an iconic and tasteful landmark that will inspire countless selfies and Instagram shots.

Carpenter Park

On the eastern edge of downtown is Carpenter Park, which is slated to be completed in spring 2022. The park reimagines the old Carpenter Plaza, which consisted of three patches of grass and trees separated by a tangle of trafficways leading to and from I-345. The roads have been realigned and simplified, stitching the 5.6-acre site together. One unique aspect of the site is that it contained an early Robert Irwin sculpture, “Portal Park Piece (Slice),” which was bisected by an off-ramp slated for removal by TxDOT.

To design Carpenter Park, the city engaged Hargreaves Jones, who completed both the initial Downtown Parks Master Plan in 2004 and its update in 2013, as well as Belo Garden. President and CEO Mary Margaret Jones says that when the parks department reached out to them about how the park could be expanded with removal of the ramp, the first thing they did was call the artist to get his thoughts. Irwin felt the site conditions had changed so much the piece no longer made sense and should be demolished. After some back and forth, he agreed to rethink it and came back with a proposal to re-orient and change sculpture based on the new site conditions. The updated artwork became the starting point for Hargreaves Jones’ design, which is much looser than that of the other recent parks. Avoiding the use of straight lines in the landscape, the firm created a granite walk that weaves through the park, framing the lawn and forming the urban gardens and the fountain oval at the intersection of Pearl and Pacific. Carpenter Park will be the largest park in downtown Dallas, and as such, it has been allowed to breathe a bit, favoring a more Olmstedian mentality over aggressive programming.

The inclusion of a fountain, of course, begs comparison to the one announced for Klyde Warren Park. The Carpenter Park fountain is expected to shoot water 25–30 ft into the air, while Klyde Warren’s, billed as the “world’s tallest interactive fountain,” will have the ability to send water 95 ft high. With the fountain, Hargreaves Jones references the Downtown Parks Master Plan, which called for vertical/iconic elements along Pacific at both Pacific Plaza and Carpenter Park. (At Pacific, this became the pavilion by HKS.)

Carpenter Park is aspirational in that its corner of downtown has yet to see significant development and activation. Parks for Downtown Dallas founder Robert Decherd, Hon. TxA, is optimistic about the area and remarks that this is “a chance to prove up the premise that great parks bring capital investments,” a phenomenon definitely observed at Klyde Warren Park. With many development sites in the park’s immediate vicinity, it is well poised to see the growth Decherd envisions.

These three parks are each a small piece in the overall growing landscape of downtown Dallas, and they represent different approaches to the design of public spaces. A city needs a variety of spaces, and no one approach is right for all locations. The spectacle of Klyde Warren’s new fountain will cater to the Instagram crowd; Thanks-Giving Square, it is to be hoped, will become a more open expression of gratitude and contemplation; and Carpenter Park will provide visitors with space to wander in a more natural setting. To fully experience downtown Dallas, you will need to visit them all.

Andrew Barnes, AIA, is the founder of Agent Architecture in Dallas.