Cloud Formation

THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON NANCY AND RICH KINDER BUILDING DELIVERS SPATIAL EXCITEMENT WITHOUT OVERWHELMING THE ART ON DISPLAY.

Architect Steven Holl Architects

Architect of Record Kendall/Heaton Associates

General Contractor McCarthy

Structural Engineers Cardno; Guy Nordenson and Associates

Climate Engineer Transsolar

Lighting Designer L’Observatoire International

Facade Consultant Knippers Helbig

Landscape Architects Deborah Nevins & Associates, Nevins & Benito Landscape Architecture

The Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, the third gallery and most recent addition to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) opened to the public this past November, completing a nearly decade-long expansion of the museum’s Susan and Fayez S. Sarofim Campus. Joining the ranks of the MFAH’s already impressive collection of architectural masterworks, the 237,000-sf Kinder Building provides more than 100,000 sf of additional exhibition space to showcase the institution’s growing collection of 20th- and 21st-century art with a marked presence of Latinx artists. Both the building and new master plan were designed by New York City-based Steven Holl Architects.

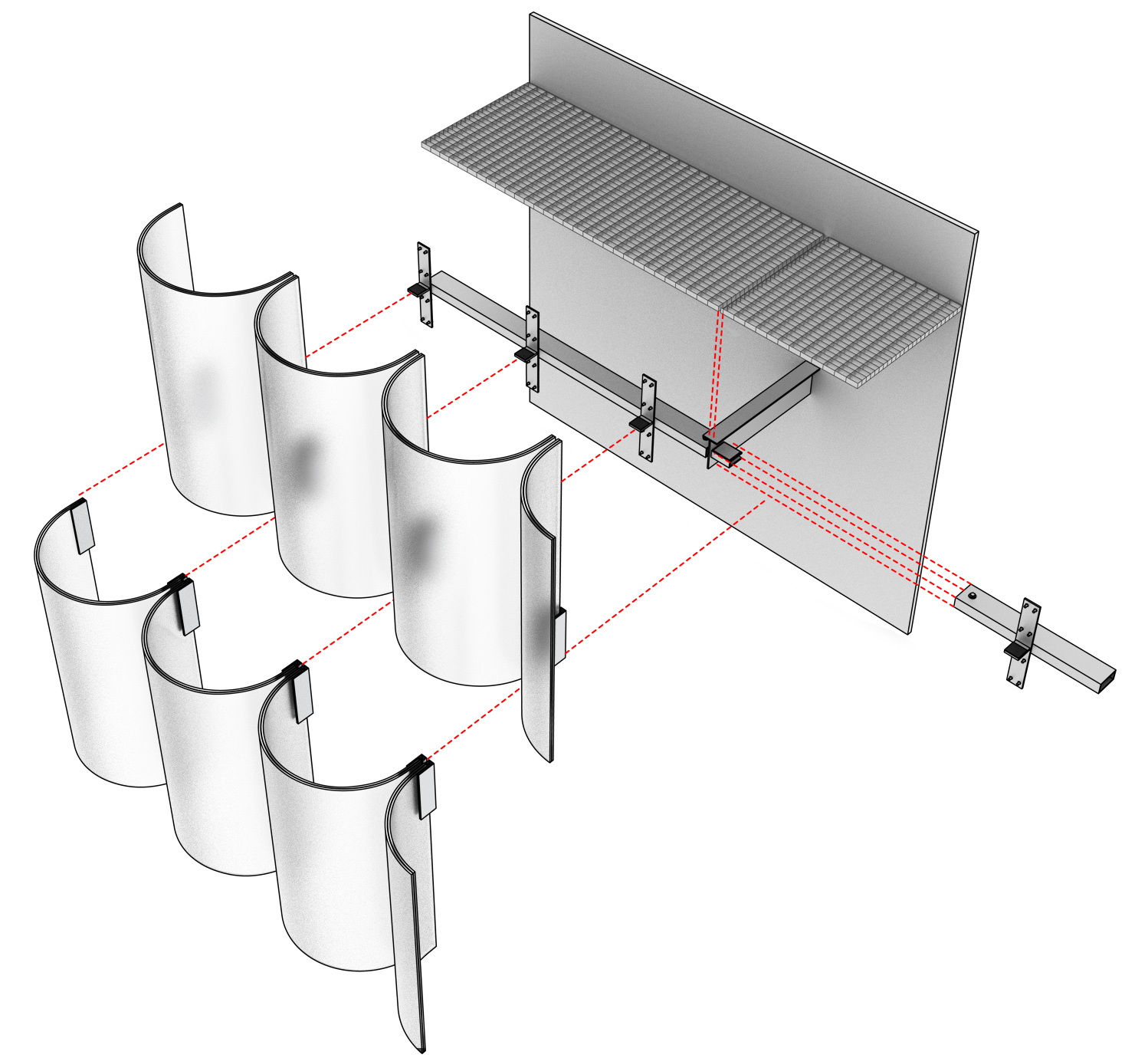

The Kinder Building has already garnered attention for its formal presence — and deservedly so. Clad as it is in luminous alabaster-like glass tubes, principal and lead designer Steven Holl describes the Kinder Building as standing in “complementary contrast” to other notable buildings on campus, such as the glass-and-steel structure of the Caroline Wiess Law Building, designed by Mies van der Rohe, and the limestone facade of Rafael Moneo’s Audrey Jones Beck Building. Comfortably resting in its wedge-shaped site, the structure expertly weaves together the Isamu Noguchi-designed Cullen Sculpture Garden — a somewhat forgotten space under the previous master plan — with the new Glassell School of Art, also designed by Holl and completed in 2018.

The distinctive 30-in-diameter arced glass half-tubes draw diffuse light into the interior spaces, providing an unusually bright, though pleasurable, viewing experience. At night, these same tubes are illuminated from within in a manner reminiscent of a lantern, a trope found within many of Holl’s designs. The tubes also serve a performative function by acting as a “cold jacket,” expelling hot air up the side of the building when the sun strikes the facade and thus reducing solar heat gain by 70 percent. While remarkable in its technical execution, the Kinder Building is in many ways more noteworthy in its departure from the traditional museum typology — both in architectural design and curatorial approach — perhaps acting as a harbinger of a broader cultural shift that is underway.

More than their objects and the walls that contain them, museums are complex reflections of the cultures that produced them. The museum as we know it today grew out of the private collections of wealthy noblemen and scholars in the 16th and 17th centuries. Coinciding with the scientific revolution and Europe’s colonial expansion into unknown continents and cultures, they were a way to understand and interpret an increasingly complex world. These collections were predominantly organized into four taxonomical categories: cultural artifacts from one’s own culture, objects from nature, objects gathered from distant places, and scientific instruments expressive of man’s ability to dominate nature. It was during this time that the seeds of Western dualism — a philosophy that came to fruition during the Enlightenment — were planted, dividing the world into polarities of subject-object, order-chaos, civilized-primitive, master-slave, human-animal, mind-body, reason-matter, culture-nature, and so on.

These private collections formed the basis for many of the great public museums established in 18th-century Europe. Simultaneously, several cultural forces arose that were fundamental to shaping the public function of the museum: Nationalism fused with colonial expansion, democracy, and the Enlightenment. One key attribute these collections shared was a scheme of linear, didactic layouts dedicated to narratives of order, development, and progress. These themes were also expressed architecturally through imposing buildings adorned with nationalist imagery, symbolizing protection and prestige, as well as identifying who controlled the materials within — many of them from colonies. Culture became a vehicle for governments to transform the masses into “citizens” — and museums, referred to as “civic engines,” were an instrument to accomplish this.

In the ashes of World War I, there arose the concept of the “white box” museum — a new museum for a new century — stripped of cultural reference and aimed at liberating art and artists from the conservative forces of history. The intent was to direct viewers toward a pure experience of the artwork. The minimalist spaces and white walls have become so ubiquitous throughout the world that museum critics have begun to question whether the “white box” has itself become another vehicle of colonialism. The late 20th century brought a variation on this trend through architectural Expressionism — Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is a prominent example — where the building emerged from the background as a work of art in its own right. Holl’s design team was satisfied with neither of these approaches. “Today, we see two types of art museums: the white box — where the building can suck the life out of the art — or the expressionistic form, where the complications of the geometry overshadow the art,” Holl says. “We are interested in a third way: where the spatial energy of the architecture is inspiring, while the primacy of art is engaging.”

When one considers the history and deeper cultural significance of the museum typology, the Kinder Building takes on new meaning. It is notable, in that it neither overwhelms nor defers to its environment, helping to restore the balance between culture and nature. Inspired by Texas’s open skies and voluminous clouds, the building’s concept, which carried through from the initial competition entry, strikes a unique balance between iconicism and reverence. “I believe in the integral relation of nature and culture,” Holl says. “We tried to merge landscape and architecture from the very first concept sketches. Thus, the landscape embracing the shape of the Glassell School and its open roof and the seven gardens that punctuate the Kinder Building are there in the initial watercolors. I worked as a landscape architect in San Francisco from 1974 to 1976 for Lawrence Halprin. This period convinced me of the urgency of landscape in city design.”

The MFAH engaged Deborah Nevins & Associates in collaboration with Nevins & Benito Landscape Architecture to unify and animate the 14-acre campus by improving the pedestrian experience through an array of public plazas, reflecting pools, and gardens, as well as improved sidewalks, street lighting, and wayfinding. “Of course, exhibition space is important,” Holl says. “However, the whole museum experience is important, and it begins when you open your car door in the parking lot.” What is normally a perfunctory schlep from the parking garage becomes an elevated aesthetic experience. Before arriving in the gallery building, visitors pass through a subterranean tunnel awash in the golden glow of 19 light sculptures — a permanent installation by Ólafur Elíasson — and punctuated by violet-hued openings to the sky, lending dynamism to the space through its changing natural light conditions. A second tunnel connecting to the Caroline Wiess Law Building features Carlos Cruz-Diez’s light installation “Chromosaturation MFAH,” a series of three hyper-saturated chambers in green, pink, and blue.

The gallery spaces are naturally lit under a “luminous canopy” roof, its concave curves mimicking billowing clouds and allowing natural light to filter to the ground floor. Pocket lighting by consultant L’Observatoire International tucked into the concrete structure accentuates the building’s curves while sharing the same visual language of the third-floor clerestory windows. Simple though thoughtfully choreographed circulation moves visitors easily from gallery to gallery. Despite reducing display space, the museum’s generous interior doorways — often manifesting as cut-away corners within a gallery — entice visitors into adjacent spaces. The dark ground plane, executed through several different treatments throughout the building, provides a sense of weight and definition to the otherwise overwhelmingly buoyant interiors. An homage to the Kinder’s Miesian neighbor, gray terrazzo covers the ground floor, while dark end-grain wood flooring covers the second and third. A tapering central stair with black treads and brass detailing creates a forced perspective that beckons visitors up through the three-story atrium. Ample floor-to-ceiling windows, accompanied by five reflecting pools along the ground floor, provide spectacular views into Noguchi’s sculpture garden — a notably democratizing move that allows passersby to view and enjoy the ground-level sculpture galleries.

Each floor of the Kinder has its own curatorial flavor. A flexible black-box gallery at street level is devoted to immersive installations, including a light-filled environment by James Turrell. The second-floor galleries are organized, as one might expect to see, by curatorial department such as the history of photography, decorative arts, and Latin American modernism, among others. The third-floor galleries feature thematic exhibitions comprised of artworks from the 1960s onward. From such sociopolitical themes as “Border, Mapping, Witness” to themes based in art theory, such as “Line Into Space,” the curatorial approach is diverse, though seemingly disjointed at first glance. On further consideration, it is remarkable in its effort to break from the dominant historical narrative and provide new cultural perspectives and interpretations.

In fact, the MFAH has spent more than $60 million over the last two decades building a collection that has led leading figures in the art world to bestow upon the museum the moniker of “premier institution for the exhibition of Latin American art.” At the time of its opening, the museum showcased works by 250 Latin American and Latinx artists, representing 24 percent of the art on display, including contributions by revered artists like Lygia Clark, Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Hélio Oiticica, Mira Schendel, and Joaquín Torres-García. In a city that is home to the nation’s fourth largest Latinx community, this is a commendable gift and an achievement in furthering representation in the fine arts. And, with approximately 90 percent of museum visitorship local to Houston, the MFAH is well-positioned to become a new type of “civic engine” to promote a more just and inclusive society.

Unveiled to the world during one of the most tumultuous episodes of the 21st century to date, the Kinder Building engenders a welcome feeling of respite and reconciliation. When asked how recent events had influenced his own perspective, Holl remarked: “I imagine that the coronavirus — this strange breath-robbing plague engulfing the world — will change humanity on earth from now on, in some ways. As the composer Arvo Pärt said, recently, ‘[C]oronavirus has showed us in a painful way that humanity is a single organism…. The coronavirus has sent us all back to first grade.’ Today, the relations of the natural world and the human-made world require the highest focus. The current global pandemic reveals the interconnected phenomena essential to our existence. Our vulnerable species — humankind — has in recent decades caused the disintegration of ecosystems of nature at a cataclysmic rate. Going forward, our species must revalue itself — we must have a transformation of consciousness.”

May we rise to the occasion.

Anastasia Calhoun, Assoc. AIA, is chair of TxA’s Publications Committee.

Anastasia Calhoun, Assoc. AIA, NOMA, is the editor of Texas Architect.

Also from this issue