Light Box

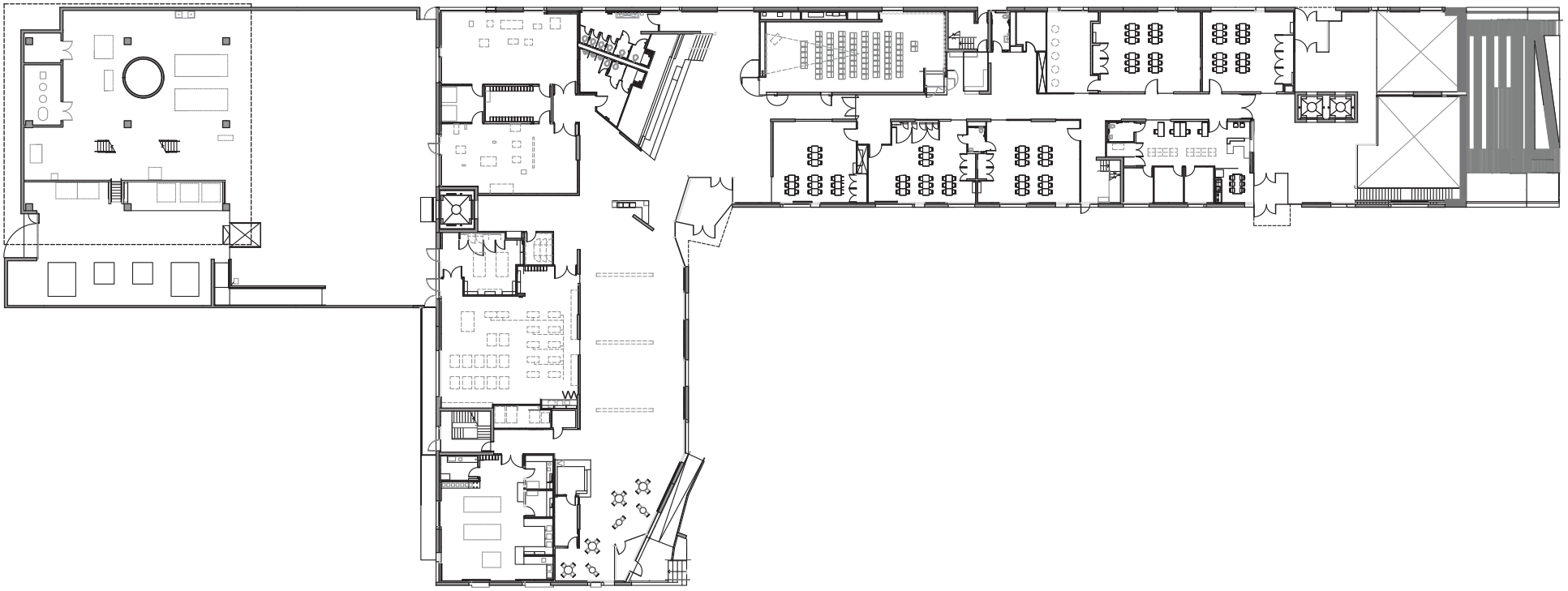

The new Glassell School of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) opened to the public last year. Designed by Steven Holl Architects with Kendall/Heaton Associates serving as architect of record, the facility expands the educational capabilities of the school. Using the additional space of the new building, the MFAH expects its annual enrollment to grow from 7,000 to 8,500 students. Of the building’s nearly 93,000 sf, about 40,000 are dedicated to studio space where, bathed in natural light, Houstonians learn and practice a range of artistic media.

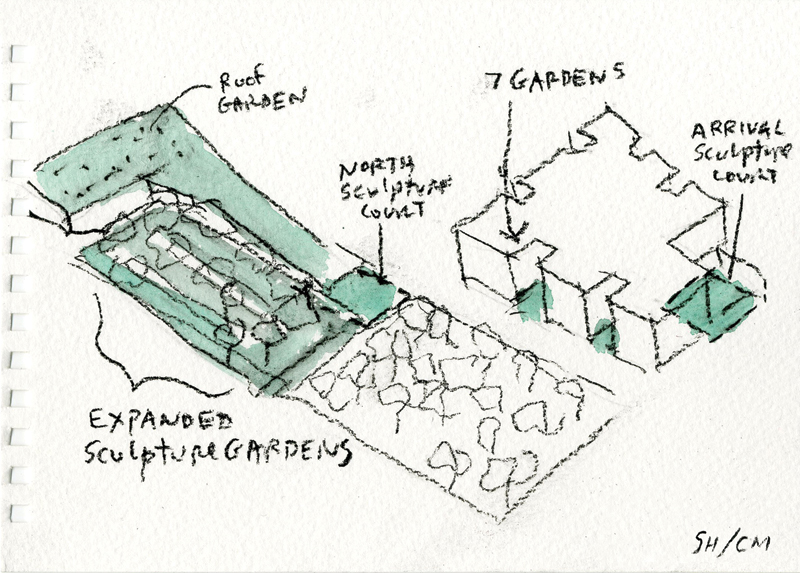

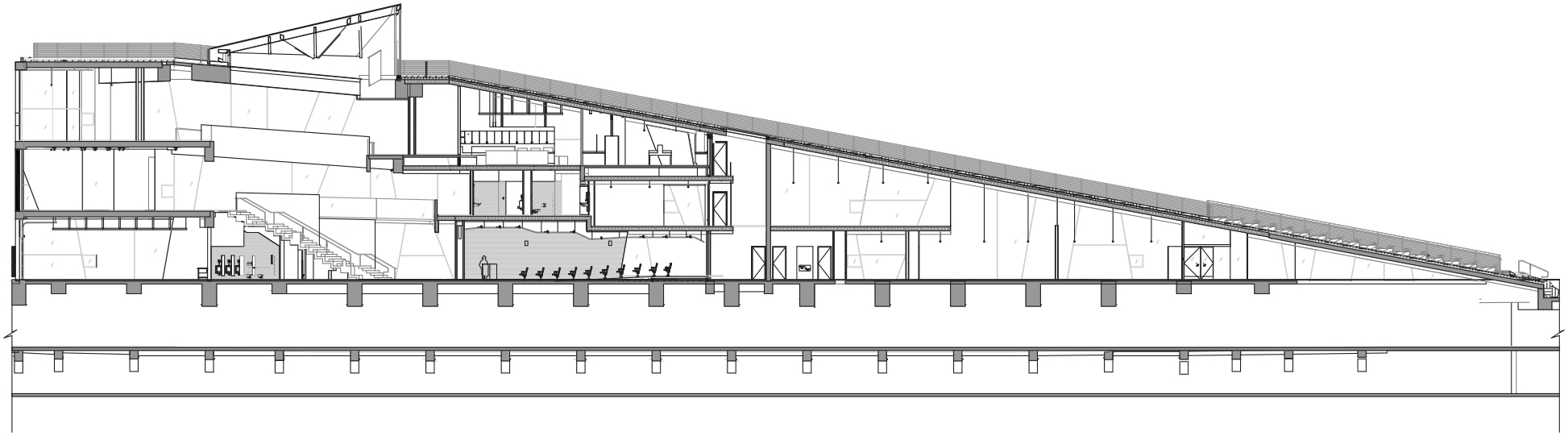

Holl’s L-shaped building opens to Montrose Boulevard, creating a plaza (designed by Deborah Nevins & Associates in collaboration with Nevins & Bonito Landscape Architecture) that opens up the space of the Isamu Noguchi sculpture garden to the north. Parking is hidden in a subterranean garage, and the facility will be linked by tunnels to the main campus and to the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, which was also designed by Holl’s office and is expected to complete construction in 2020. The Glassell’s structural facade consists of 178 precast concrete panels, manufactured in Waco by Gate Precast. The sides of some pieces tilt at an 11-degree angle, responding to the slope of the roof and the precedent of Noguchi’s angled concrete walls nearby.

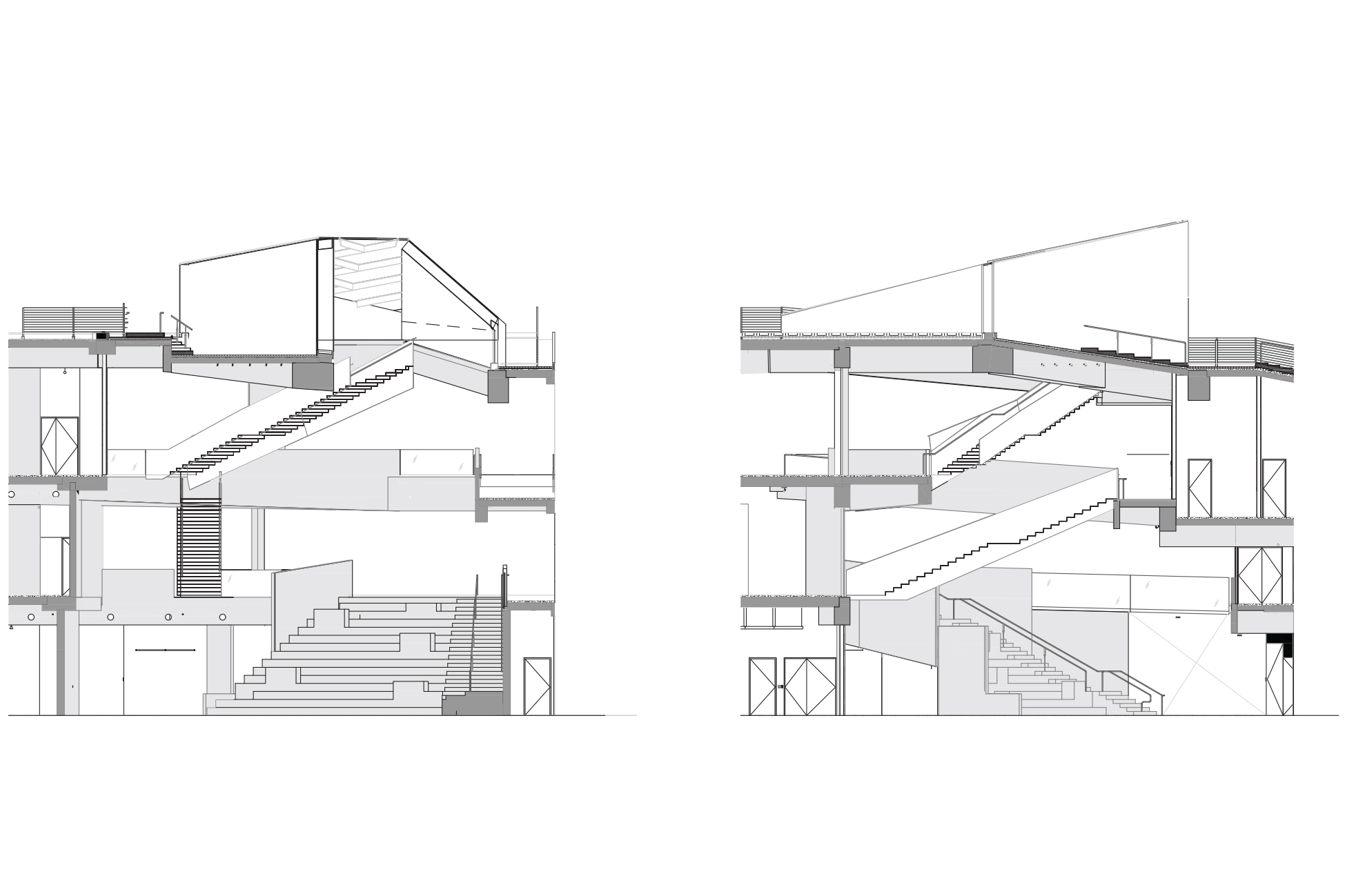

The building and plaza replace the prior Glassell School, built in 1979 and designed by Houston architect Eugene Aubrey, FAIA Emeritus, of S.I. Morris Associates. The new Glassell borrows a handful of moves from its predecessor. On the outside, the elevation is organized by concrete bands that register floor plates, and large expanses of glazing that evenly distribute light — what was once a facade of glass block is now composed of massive insulated glass units, manufactured by Cristacurva in Mexico, with an additional third pane that is treated to make the glazing (Knippers Helbig was the facade consultant for the project). The difference showcases how far glass as a material has come in the past 45 years. The skewed apertures supply ample natural light to internal work spaces during the day and at night glow a cozy yellow.

Inside, the building is dedicated to light. A central atrium is illuminated from above; sunlight sinks and settles through the atrium. The spaces are materialized in an austere palette of white paint, gray concrete and steel, and coated blue glass; they feel deliberately unfinished and loft-like, which rightfully places the emphasis on the colorful art produced by the students. Thirty-six new studios and related exhibition spaces are the heart of the school, which also now houses the Core Residency Program, a celebrated opportunity for early-career artists and critics. Well-known alumni of the program include Kalup Linzy (2013), Julie Mehretu (2009), Tony Feher (2001), Bill Viola (2000), Mona Hatoum (1998), Roni Horn (1996), James Turrell (1995), Richard Tuttle (1992), and John Baldessari (1982), among many others.

Each of these studios is washed with light that spreads out from the large apertures. Work surfaces — tabletops and easels — are evenly lit; there are no harsh shadows. The light, bouncing around, becomes a solid chunky thing as it expands to fill the whole room. A 3-ft-by-3-ft operable window with clear glazing provides a small connection to the outside environment, useful during Houston’s three tolerable seasons. The tall spaces are enjoyable. It is easy to trust that they are ideal places to paint, draw, and sculpt. In a sense, the new Glassell is rough infrastructure, as it provides the framework for students of all ages to have an educational artistic engagement with media.

Jack Murphy, Assoc. AIA, is a regular contributor to TA and a master of architecture candidate at Rice University.