Exhibition Review: The Idle Archaeologist

Between the years 1963 and 1978, the artist Ed Ruscha generated a series of small photography books in parallel to his production as a painter. Located at the intersection of pop, conceptual art, and documentary photography, these unassuming publications would go on to occupy an outsized space in the development of western culture, influencing several generations of artists and architects to the present day.

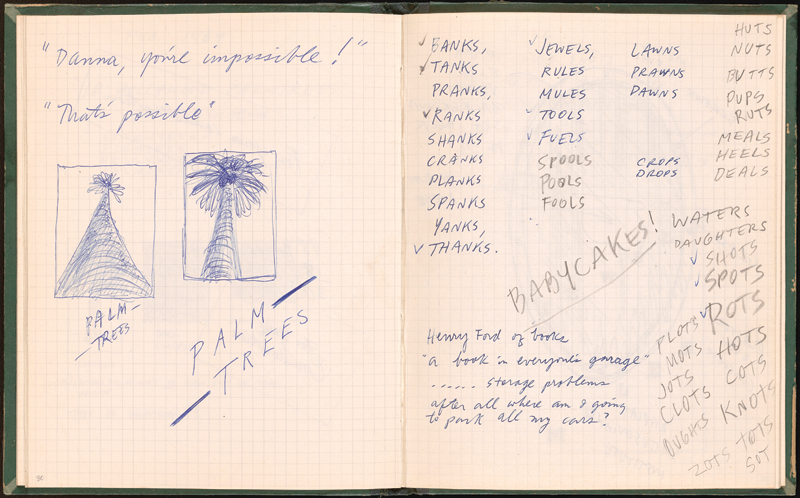

A recent exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin, curated by Jessica S. McDonald, provides a comprehensive panoramic of Ruscha’s publication practices and delves deeper into eight of these books, presenting them within the expanded context of a constellation of related drawings, photographs, and prints — a grouping that includes an abundance of unpublished archival materials featuring Ruscha’s production notes and sketches.

Accordingly, in the exhibition, each of the books becomes the center of a small web of documents that contains not only the preparatory materials put forth in advance of publication, but also subsequent works in other media in which the artist continued to elaborate on the motifs and images [dwelt upon] in the books. As a result of this generosity — the expansive layout features more than 150 objects — the exhibition delivers a vivid immersion into Ruscha’s multimedia universe in what becomes a mesmerizing visual experience. Perhaps more importantly, such generosity allows McDonald to re-frame the work of Ruscha from a contemporary perspective, through a light-handed curatorial strategy that relies primarily on visual evidence as opposed to wall text.

Titled “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance,” the exhibition looks primarily at those publications in which Ruscha focused on his immediate urban environment, and by doing so, it highlights the protagonism that architecture has enjoyed in Ruscha’s work from the outset of his career. This relationship is apparent in “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” (1963), with its selection of quasi-random roadside buildings, but it is also evident in the curation of dingbats and small housing blocks found in “Some Los Angeles Apartments” (1965), and in the asphalt surfaces of “Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles” (1967), not to mention in the backyard scenes of “Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass” (1968).

Through both its title and its selection of works, the exhibition produces a reading of Ruscha’s process as a survey of the reality around him that gradually turns into an effort to identify, isolate, and re-present a specific series of urban phenomena. According to this reading, the work oscillates between an ambiguous, almost aimless, effort at selection and a series of moments of declared specificity — between indifference and a sense of fixation. In each of these publications and their subsequent re-elaborations in different media, we find a particular tension between a sustained effort to remain neutral — to obscure the emotional relationship between the artist and his subject matter — and moments when his fascination emerges and becomes evident to the viewer. This tension is perhaps best exemplified in the contrast between the intentionally imperfect black-and-white photographs summarily compiled for the publication of “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” and the full-color and highly idealized versions of one of those same buildings — the now-famous Standard Station in Amarillo, Texas that Ruscha produced in a series of oil paintings and silk-screens over the following years. If Ruscha, the idle archaeologist, was able to remain mute about his own response to car urbanism throughout the production of the book, any semblance of neutrality abandons him with his compassionate and heroic rendering of the tiny building in painting.

It was surely ambiguities in Ruscha’s work that made him such a pivotal and influential figure throughout the 1970s: His internal contradictions account not only for the diversity of readings that the work gave rise to, but also for the difference in the way his work was treated by the art and architecture scenes. On the one hand, the customary understanding in the art world, as evidenced by his early appearances in Artforum, was that Ruscha’s choice of subject matter was opportunistic — that he chose the gas station motif as a provocation for the same reason that he chose the cheap run-of-the-mill book format: as a challenge to the primacy of large-scale oil painting, or even handmade artist books. Within architecture, on the other hand, and starting with the early appreciation of Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Reyner Banham, the understanding was that Ruscha’s focus on the city was central to his project, which architects came to regard almost exclusively as an explicit effort to make sense of a new postwar urban reality that was yet to be documented and theorized.

Judging by the documents presented in the exhibition, the truth is probably that Ruscha was neither so calculating nor so earnest. His was likely neither a cynical pursuit of shock value, nor a populistic validation of a new vernacular — that is to say that his contradictions were sincere and his artistic merit lies in his capacity for devising a new type of artwork that delivers such conflicted feelings to the viewer without providing a pre-established response. While it is as easy to understand Ruscha’s work as being as inwardly driven as outwardly so — either can be demonstrated with ease — each of these conceptions is also incomplete, and it is precisely the merit of an exhibition like “Archaeology and Romance” that it presents them to us not only as compatible, but as profoundly intertwined, as it opens up a renewed consideration of their relevance for our time.

Jesús Vassallo is currently the Gus Wortham Assistant Professor at Rice University School of Architecture.