Transitions to Well-Being

Each year as summer turns to fall, many young children step inside a school for the first time, marking a celebrated milestone in the journey to adulthood. But this can be a challenging experience for a child. In particular, the transition from a familiar and safe home life to an unfamiliar and sometimes institutional-feeling school can be an impediment to growth.

New surroundings, routines, and relationships can be overstimulating. Studies show that feeling safe and secure is an essential requirement for learning and development to happen. With this awareness in mind of the psychological impact of design on a building’s users, how can we craft early childhood environments that welcome, comfort, and inspire?

As designers, we strive to create sanctuaries where new learners can flourish, discovering and developing their potential. Design should balance the tangible elements—scale, shape, color, and texture—with features that transcend a physical description, such as biophilic connections, acoustical design, and sunlight, all of which can shape a child’s sensory experience.

Consider a young student’s transition from home to school. Often school buildings can be cold, institutional places, featuring sharp edges and intense colors, a jarring contrast from the warm and comforting home environment, which typically includes natural materials like wood and fabrics in comfortable color palettes and textures. It can be stressful for children when they enter a space for the first time and encounter an environment that feels so disconnected from their home environment. Biologically, there’s something evolutionary in the way we see sharp lines and corners that puts us on edge. Intentionally including some gentle curves in the design, such as biophilic wall coverings or curved shapes in the flooring as you round a corner, can have a pleasing and calming effect on the brain.

Scale and Soothing Spatial Geometry Can Enhance Learning

At a functional level, it is important to remember that a small child’s eye level and arm reach are much different than that of an average-sized adult. This consideration should inform the selection and placement of the physical elements children interact with. For example, a windowsill placed lower on the floor might allow a small child to benefit from the view to the outdoors.

The scale of rooms and spaces should also be considered. An unusually long hallway or an overly large, cavernous space has the effect of making small children feel lost and overwhelmed by their surroundings.

The psychology behind shapes suggests the human brain associates sharp angles with alertness and potential threats, while curving shapes, which occur more often in nature, convey safety and approachability. Biophilic design principles are not new, and we can introduce them into our spaces in many ways, including through lighting shapes, furniture shapes, and materiality. Research suggests curved forms are consistently rated as more pleasing and less threatening. These forms can help soften the interior environment and possibly create intuitive emotional cues.

This idea is reinforced by emerging psychology studies. The systems in the brain responsible for emotion and regulation—particularly the prefrontal cortex—mature more slowly than the reactive emotion centers, such as the amygdala. As a result, children can be more sensitive to environmental stressors and have fewer tools to self-regulate. Since heightened emotional states can impair attention and learning, spatial environments that help reduce stress and perceived threats can support a child’s emotional regulation and cognitive learning functions. Here is where environmental cues can help: soft shapes and soothing spatial geometry can support feelings of emotional safety by acting as a nonverbal, co-regulatory tool in spaces. These small spatial gestures can make a big difference if they calm the nervous system and allow the cognitive learning process to function more effectively.

This idea can be explored in Pfluger Architects’ design for Hidden Lake Elementary School in Pflugerville. In the shared learning space, organic moss-like seating elements invite play and comfort. Their soft, rounded forms serve as both whimsical visual anchors and tactile, grounded places for rest or play. Overhead, large, curved LED light fixtures mimic natural forms—the soft seat below helping to unify the space visually. Together, these elements transform the learning environment into one that is emotionally accessible and engaging.

Color is Cultural

Color can play a profound role in shaping a child’s sensory perception and emotional response, which is crucial when designing environments to support learning and cognitive development. While vibrant, highly saturated hues can energize a space, research indicates that an overabundance or poor coordination of colors, along with large quantities of patterning, can overstimulate children, especially those with sensory sensitivities.

We can also use color when designing for belonging; color can reflect culture and help us acknowledge home environments. For example, historically in the United States, red has been associated with signals such as “stop” or “alarm.” Research indicates red can contribute to eye strain and irritability in specific contexts, particularly under prolonged exposure. Conversely, a study on Japanese elementary and high school students revealed a preference for red, underscoring the cultural influence on color preferences. Therefore, when designing spaces for children, to cultivate a feeling of belonging it is essential to consider context—and what “home” means for those students. In the case of the George Peabody Elementary School in Dallas, colors were used as accents in energized spaces like the cafeteria. The selected hues—purple, yellow, green, and blue—align with the top preferences for children, while the remainder of the space remains neutral. With enhanced natural daylighting, the colors activate the environment without creating visual overwhelm.

Acoustics and Materials for Positive Learning Outcomes

Acoustical quality is an important but often overlooked school design factor that directly impacts student learning outcomes and teacher effectiveness. Poor acoustics inside classrooms negatively affect the teaching and learning processes, especially at the lowest grades of education, making proper acoustical design critical for younger students who are developing foundational learning skills. Suitable acoustical design in classrooms and other learning spaces enhances speech clarity and limits background noise to protect speech quality for both the teacher and student. Higher speech intelligibility results in a positive effect on learning outcomes.

The measurable benefits extend beyond academic performance to encompass behavioral and health outcomes. Studies have shown that following improvements to classroom acoustics, teachers have reported higher student engagement and improved results in on-task behavior.

Acoustic design strategies include:

- Creating acoustic buffer zones between noise-sensitive classrooms and areas prone to higher activity and noise levels.

- Reducing reverberation in learning spaces through the use of soft and sound-absorbing materials such as rugs, fabric curtains, cork boards, and acoustical wall or ceiling panels.

- Adding soft tips or pads to the bottoms of tables and chairs.

- Adding a speech-reflective zone above the teacher’s presentation area for passive audio distribution.

- Adding an audio distribution system, including a teacher microphone and distribution speakers.

Materials in a safe and welcoming space should evoke comfort, not just durability. Sometimes a home or school is a first sanctuary space—how can we create spaces that are filled with soft, tactile, natural materials like wood and fabric, along with warm colors? In the past, institutional buildings trended toward hard, cold finishes that felt alienating. Studies in environmental psychology indicate that children have strong tactile sensitivity, and overly sterile environments could provoke unease.

The design of the Dorothy Martinez Elementary School in Denton County challenges that paradigm. In the school’s dining and gathering space, a mix of materials creates an experience that feels both functional and emotionally grounded. Warm-toned wood-looking luxury vinyl tile is used, balancing the acoustic ceiling tiles designed to absorb excess sound—a vital feature in large active spaces. Tall, wooden-slat panels with felt backing provide acoustic treatment as well and physically warm the double-height volume, while floor materials subtly shift in tone and texture to define space without overwhelming it. The effect is inviting and sensory-aware.

Materiality also affects what we hear and how we feel. Poor acoustics can be a barrier to learning, increasing cognitive load and making speech harder to understand. This influences an emphasis on using sound-absorbing materials to help quiet a room while creating a warm, grounded auditory landscape where children can flourish.

Lighting Design for Well-Being

Lighting design serves as a fundamental environmental factor in early childhood learning spaces, directly influencing children’s physical development, cognitive abilities, and overall learning experience.

Research demonstrates that exposure to appropriate lighting can improve concentration, enhance cognitive abilities, and regulate sleep patterns. Conversely, poor lighting can lead to irritability, restlessness, eye strain, and difficulty with focus and attention.

The benefits of natural daylight are significant for young learners, as increased light during the daytime is broadly associated with beneficial effects on social-emotional, cognitive, and physical health outcomes. Exposure to bright light may significantly increase the brain’s ability to grow new pathways and retain information. Bright light boosts mood and concentration, which is crucial for maintaining young children’s engagement during learning activities. Lighting solutions should support both developmental needs and educational objectives in early childhood settings.

Connection to Nature

The integration of natural elements and biophilic design principles in early childhood learning facilities provides substantial developmental and educational benefits that extend across multiple domains of child growth.

Studies have shown exposure to nature has many benefits, including social development, better concentration, increased short-term memory, and reduced stress. Connections with nature can also engage the senses and spark young learners’ curiosity.

When it comes to incorporating biophilic elements in the design of schools and early childhood learning areas, there are several strategies:

- Biophilic and natural elements can be incorporated into interior environments and learning spaces through plants and living walls.

- Views to outdoor natural areas can be integrated.

- Direct access can be provided to outdoor areas, courtyards, playgrounds, sensory gardens, and growing gardens.

Emotions Shape Learning

Children can arrive at school in different emotional modes, and emotional loads can vary. Some might experience nervousness, and others could be overstimulated by the transition from home to school environments. Design that accounts for this range of emotions can offer pathways toward self-regulation. Thoughtful spatial programming that accommodates this emotional diversity is essential in cultivating emotional regulation and feelings of internal safety. Recent journals on education neuroscience emphasize the importance of autonomy, transition, and environmental cues in supporting a child’s emotional development.

Design can also create zones of refuge, allowing students to find the sensory input or calm they need in the moment. This aligns with research showing that emotional safety is a prerequisite for executive function and self-regulation—critical components of learning to read.

This principle is beautifully explored at Dorothy Martinez Elementary School and Houston’s Braeburn Elementary School, where quiet nooks and pods are embedded into the building. Bold sculptural reading pods were created at Dorothy Martinez Elementary, while dome-like sensory alcoves at Braeburn Elementary offer enclosures that support withdrawal and emotional recalibration. These carved-out sanctuaries invite quiet focus or co-regulation among peers. They are not just playful moments in the interior architecture—they reflect how built environments can influence brain networks responsible for regulation and cognitive control

Positioning these nooks in activated areas and circulation zones means children don’t have to travel too far to access these environmental tools. They can help support self-direction while reducing emotional and physical fatigue—important for younger learners who may be overwhelmed by longer transitions.

Creating a safe and welcoming environment can have a profound impact on our well-being, improving cognitive functions and opening doors for better learning outcomes. Intentionally designed spaces and transitions allow people to experience well-being, emotional regulation, and safety within their space. School buildings in particular can be sanctuaries—places where stressors are minimized and students’ cognitive functions are enhanced, all as a result of thoughtful, empathetic design. A designer’s conscious use of scale, color, outdoor views, and natural light plays a vital role in reducing the anxiety associated with transitions between spaces.

ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTORS

Christian Owens, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, BD+C

Brenda Swirczynski, MSc, ALEP

Alexander Wickes, RA, LEED AP, BD+C

RECOMMENDED READING

Augustine, S. “20 Things Neuroscientists Want You to Know.” NeoCon 2024 Conference Findings, June 2024. designwithscience.com.

Bar, Moshe, and Maital Neta. “Visual Elements of Subjective Preference Modulate Amygdala Activation.” Neuropsychologia 45, no. 10 (2007): 2191–2200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.008.

Barrett, Lisa Feldman, and Ajay B. Satpute. “Large-Scale Brain Networks in Affective and Social Neuroscience: Towards an Integrative Functional Architecture of the Brain.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 23, no. 3 (2013): 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2012.12.012.

Blair, Clancy, and C. Cybele Raver. “School Readiness and Self-Regulation: A Developmental Psychobiological Approach.” Annual Review of Psychology 66 (2015): 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221.

Christensson, Jonas. “Good Acoustics for Teaching and Learning.” In Euronoise 2018 Conference Proceedings, 1755–1759. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4987169.

Elliot, Andrew J., and Markus A. Maier. “Color Psychology: Effects of Perceiving Color on Psychological Functioning in Humans.” Annual Review of Psychology 65 (2014): 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115035.

Evans, Gary W. “Child Development and the Physical Environment.” Annual Review of Psychology 57 (2006): 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190057.

Glogar, M.I., A. Sutlovic, I. Matijevic, and V. Hajsan-Dolinar. 2017. “Preferences of Colors and Importance of Color in Working Surrounding of Elementary School Children.” In INTED2017 Proceedings, 6578–6585. IATED. https://library.iated.org/view/GLOGAR2017PRE.

Imai, M., N. Saji, G. Große, C. Schulze, M. Asano, and H. Saalbach. 2020. “General Mechanisms of Color Lexicon Acquisition: Insights from Comparison of German and Japanese Speaking Children.” In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 3315–3321.

Immordino-Yang, M. H. 2015. Emotions, Learning, and the Brain: Exploring the Educational Implications of Affective Neuroscience. New York: W. W. Norton.

Martin, R. E., and K. N. Ochsner. 2016. “The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation Development: Implications for Education.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 10: 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.06.006.

Maule, J., A. E. Skelton, and A. Franklin. 2023. “The Development of Color Perception and Cognition.” Annual Review of Psychology 74: 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032720-040512.

Braden Haley, RA, AIA, is a senior project manager with Pfluger Architects, where he specializes in the design and management of K-12 educational facilities.

Katherine Wiley, RID, IIDA, is an interior designer with Pfluger Architects committed to shaping learning environments that foster belonging, focus, and emotional safety for all learners.

Also from this issue

Housing Policy and the Quest for Shelter

A new model for neonatal care

Austin’s Stealth House defies convention.

The making of El Paso’s Temple Mount Sinai

A bustling community center for Northwest Austin

Exploring new possibilities for green burial

A new home for a West Texas church

The first phase of UT Dallas’s new arts complex revealed

Empathic Design: Perspectives on Creating Inclusive Spaces

Elgin Cleckley, NOMA

Island Press, 2024

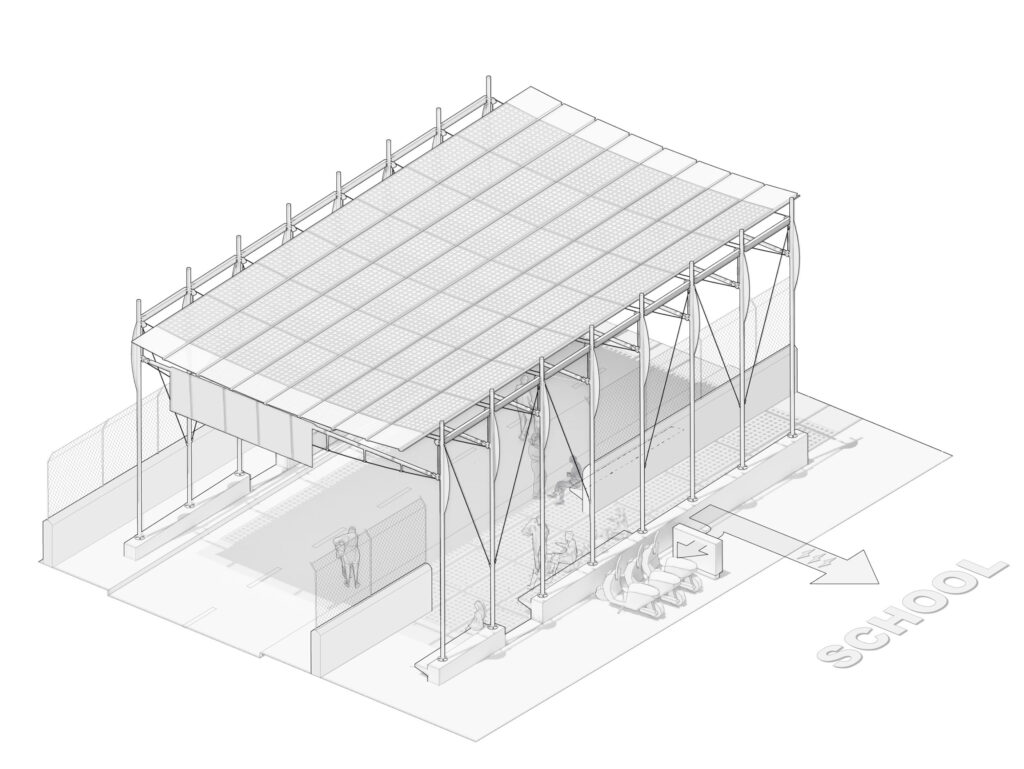

Creating the Regenerative School

Alan Ford, FAIA, Kate Mraw, and Besty del Monte, FAIA

Oro Editions, 2024