Toward a Landscape of Presence

Exploring new possibilities for green burial

Although I am a landscape designer by day, I spend my Fridays bearing witness as people navigate the threshold between life and death.

I am a death doula. My days at ABODE Contemplative Care for the Dying are spent with people who are dying and their loved ones.

Through my work, I have learned that my role is not to fix or to solve, but to create presence: to hold silence when words are not enough, to offer ritual when time feels fractured, and to remind families that grief is not an interruption of life, but part of it.

Each day looks different because each death is as unique as the lives of the people I meet. Sometimes I sit bedside, adjusting pillows, washing hands, or offering conversation. Other times I make tea for a family member, clean the house, or greet visitors at the door. And often, I simply sit in silence, holding space.

This work has changed me. It has taught me that grief is not meant to be efficient or hidden away. It is meant to be witnessed, to move through bodies and communities, and to be metabolized into wisdom.

When I return to my work in landscape architecture, I carry these lessons with me. On paper, the two professions may seem unrelated. But to me, they are inseparable. Both require us to honor the cyclical nature of all things. Both involve a deep understanding of thresholds, because what is a death doula if not someone holding your hand as you make your way through your final threshold in this life? And both are about creating spaces that hold transition, invite presence, and direct our attention to what matters most.

Death doula is a relatively modern role that has come about in Western society because of our cultural separation from death and dying. Our ancestors did not have the luxury of forgetting death; they lived closely with its rhythms, moving through its raw liminality as an integrated part of everyday life. There were no distant institutions to hide the dying, no sanitized spaces far removed from the living. Death happened amid life, and life was shaped by it.

In recent years, the role of the death doula has emerged as a response to the growing medicalization of death and dying. As more people spend their final days in hospitals, nursing homes, or other institutional settings, many families have found themselves distanced from the intimate, communal experience of caring for the dying. Death doulas step into this gap, offering support, advocacy, and companionship. We help individuals and families navigate the profound emotional, spiritual, and logistical terrain of the end of life. We are not medical workers, but we work alongside them, easing some of the burdens that accompany dying so that already overtaxed doctors and nurses can focus on their essential tasks of medical care. Our work is to rehumanize death, returning it to the realm of family, community, and land. In many ways, the rise of death doulas signals a cultural hunger for reconnection and meaning in the face of loss.

Just as families are beginning to reclaim their role in end-of-life care, we are also witnessing a parallel shift in the legal landscape around burial itself. This shift opens the door to reimagining cemeteries not only as places of interment, but as landscapes which remind us that death is an essential part of life. They can become vital spaces where memory, ecology, and renewal are held in balance, and where life is honored just as fully as loss.

It is through this dual lens, the lens of designer and doula, that I now look at Texas cities and ask: Where do we allow grief the space to move freely? Where in our landscapes do we acknowledge death as natural, and allow it to teach us how to live?

A Legal Shift: Cemeteries Back Inside the City

In 2023, Texas quietly passed House Bill 783. The law overturned long-standing restrictions that had prohibited new cemeteries within city limits. For decades, cemeteries were pushed outward, exiled to the urban fringe, a pattern echoed across much of the United States. This separation was not only about land use but about cultural distance: by relocating burial grounds away from daily life, cities reinforced the idea that death was something to be managed at the margins, not integrated into civic experience.

HB 783 reopens the possibility of inviting new burial landscapes into the civic fabric. At first glance, this might seem like a minor adjustment to land use regulation. But it represents something much more profound: a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reconsider how we hold space for death within our communities. The return of cemeteries to the city invites us to ask new questions: What role should they play in civic life? How might they be designed not as single-use zones of mourning, but as places that contribute to ecological health, cultural meaning, and public gathering? They can instead be reimagined as multifunctional civic landscapes that respond to the needs of both death and life, expanding the way we understand land, memory, and community in the process.

Designing for Death and for Life

To seize this opportunity, we must reconsider the cycle of life—and death. Too often, we imagine life as a straight line: birth, living, then death as a final stop. Yet the land teaches us otherwise: everything moves in cycles, where every ending becomes the ground for a new beginning. Burial grounds, then, should not be static destinations that simply hold us at the end of the line, but living landscapes that keep the loop in motion, nurturing renewal alongside remembrance.

And keeping this loop alive is not only about ecological processes but also about how cemeteries can welcome the presence of the living by creating spaces where gathering, walking, and community are encouraged. Instead of being isolated and hidden, cemeteries can be integrated and generative places in the community. These landscapes can also accommodate the current growing interest in alternative, ecologically sensitive end-of-life options, including green burial and human composting.

Earlier this spring, I was awarded TBG Partners’ Idea Lab fellowship, the firm’s in-house research and development incubator, to delve more deeply into the concept of green burial and explore how cemeteries might transcend their traditional functions. Green burial, a term introduced in the United States in the 1990s and codified through organizations such as the Green Burial Council, describes burial practices that minimize environmental impact and preserve natural landscapes, avoiding embalming chemicals, non-biodegradable caskets, and concrete vaults. In visiting pioneering sites in the U.S. and Europe, I saw how this shift is already underway.

At Penn Forest Natural Burial Park in Pennsylvania, for example, the approach is holistic. The park is not only a burial ground but also a sanctuary for the living. It hosts farm-to-table dinners with produce from its greenhouses, goat yoga, a community cut flower garden, and seasonal celebrations, all of which foster a deep connection between visitors and the land. At the same time, it integrates a nature preserve for native wildlife and plants, emphasizing ecological stewardship.

Similarly, West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia has transformed its historic grounds into a vibrant community space. Its green burial area, Nature’s Sanctuary, is a certified SITES Gold landscape featuring native meadows and hand-dug graves to minimize environmental impact. Just as importantly, the cemetery is linked to the city’s trail system, making it a beloved neighborhood park as well as a burial ground.

Together, these examples demonstrate what becomes possible when cemeteries are seen as part of the civic fabric: they can be more than places of interment. They can cultivate relationships with the land, with mortality, and with community life. Given the preciousness of land, spaces designated for burial should be multipurpose. When people have the chance to experience and care for the landscapes where their loved ones are buried, they develop a meaningful attachment that fosters stewardship, sustaining both memory and renewal for generations to come.

During my travels in Stockholm, I observed a culture where cemeteries are seamlessly embedded within parks and fully integrated into daily life. The backyard of my hotel happened to be a cemetery, and even on a cold spring morning, it was alive with activity. People passed through on their way to work, some lingered to play with their children, some were taking their dogs through for a walk, while others paused to visit a grave. The scene struck me deeply: death and life coexisted there organically because they have always been allowed to exist together, intertwined and normalized, reminding me that cemeteries can be both active civic spaces and sacred landscapes of remembrance.

A Case Study: Southside San Antonio

The question now is how these design-forward ideas can begin to take root in Texas, where doing so requires public buy-in for a relationship with death that differs from prevailing cultural norms. That challenge is already being tested. In late 2024 in San Antonio, Service Corporation International (SCI) applied to rezone an 80-acre parcel near the Mission del Lago development on Highway 281 south of Loop 410 for a cemetery, funeral home, and associated cremation facilities.

The proposal quickly drew concern from neighboring homeowners, who raised issues around lost tax revenue (cemeteries are tax-exempt), potential negative impacts on property values, and the shift in land use from residential to special purpose. City officials and SCI representatives countered that cemeteries can operate quietly “like a park,” with low traffic and minimal disruption, making them viable civic landscapes if thoughtfully integrated. They noted that cemeteries are quiet neighbors, that proximity can ease the burden on grieving families, and that the site could provide much-needed green space in a part of the city where parks are scarce.

The proposal remains contested and requires special use authorization, but the debate itself is instructive. It shows that, in Texas, cemeteries, in the public’s mind, are still largely perceived as burdens rather than assets. Yet within that tension lies opportunity. The San Antonio case illustrates how the treatment of death and the spaces we dedicate to it shapes civic life.

The concerns voiced in San Antonio about visibility, land values, and urban priorities should not be dismissed. They reveal cultural anxieties around death, but they also highlight the design work ahead. If cemeteries are perceived as undesirable, how might we instead design them as places of beauty? If they are seen as economically unproductive, how might we design them as ecological and social assets? If they are feared as reminders of mortality, how might we design them as teachers of continuity, care, and the cyclical nature of life?

This is the invitation embedded in HB 783. To answer it, we must approach cemeteries not as single-purpose zones but as layered landscapes woven into the life of the city itself. Yet the challenge of designing such spaces does not exist in isolation. Our cities and landscapes are themselves under the unprecedented strain of cascading ecological, social, and cultural pressures that shape how we live and how we die.

The Larger Threshold We Face

All of this unfolds against a wider backdrop. In Texas, ancient springs are drying up; summer heat reaches deadly extremes; winter storms paralyze cities; and catastrophic floods unleash unimaginable destruction while ecosystems continue to shift and unravel. These challenges are no longer distant possibilities, but realities we face. And with them comes grief: for what is lost, for what is changing, and for what we cannot control.

When we acknowledge grief, we do not have to bear its weight alone. We can recognize grief as a force that moves through us, shaping how we understand life, care for others, and connect to the land. In landscapes where death is held openly, grief can breathe. It can be witnessed, felt, and returned to the world as attention, care, and renewal.

We are moving through a threshold—one that calls for a different way of being human and a different way of shaping our cities. A landscape of presence does not attempt to fix grief; it holds it, cradles it, allows it to exist alongside life. Here, death is not erased or feared but embraced as part of the living world.

As a death doula and landscape designer, I have seen how there is a deep hunger for this in the collective: a hunger for connection, presence, and meaning. A hunger for the understanding that grief is not here to interrupt your life, it is the soil in which hope, care, and joy take root because grief is not just sorrow. It is also praise, the deepest way that love can honor what it misses.

If we are willing to meet grief with design that listens, that opens space instead of closing it off, our landscapes and our communities can hold us fully. Fragile and resilient, joyful and grieving, alive in ways that honor the cycles of life, death, and renewal rooted in the land and in one another. This is what a landscape of presence asks of us: to create spaces and to inhabit them ourselves, where we can sit with all that grief reveals, even its uncomfortable truths, and allow those truths to teach us how to live, how to care, and how to be present with one another.

Leah Gundrum, MLA, is a landscape designer at TBG Partners and a death doula. She focuses on creating spaces that reflect the beauty of these natural cycles. As she continues to grow in her career, she remains driven by the belief that thoughtful design can reconnect people to nature, culture, and each other, offering solace and meaning in an increasingly complex world.

Also from this issue

Housing Policy and the Quest for Shelter

A new model for neonatal care

Austin’s Stealth House defies convention.

The making of El Paso’s Temple Mount Sinai

A bustling community center for Northwest Austin

A new home for a West Texas church

The first phase of UT Dallas’s new arts complex revealed

Empathic Design: Perspectives on Creating Inclusive Spaces

Elgin Cleckley, NOMA

Island Press, 2024

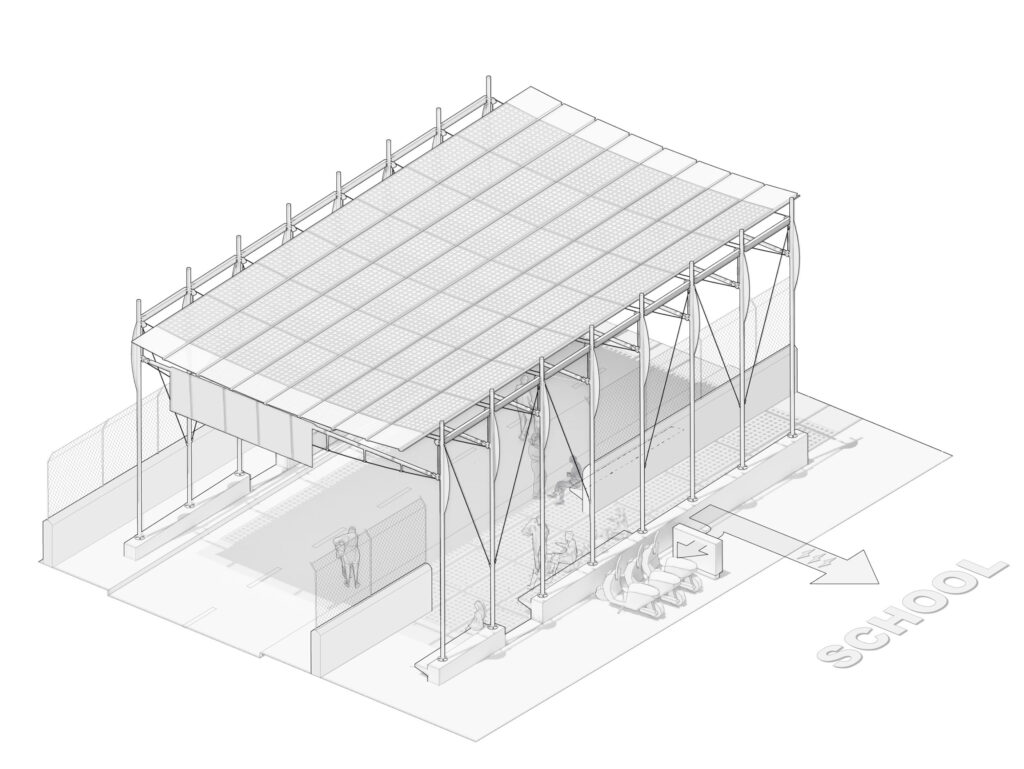

Creating the Regenerative School

Alan Ford, FAIA, Kate Mraw, and Besty del Monte, FAIA

Oro Editions, 2024

Leah this is terrific- beautifully written and thought provoking! Best, Eddie

Genesis 3:19 (“…for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”)