Kerchunk!: Reflections on For an Architecture of Reality

“There are valued times in almost everyone’s experience when the world is perceived afresh.”

This is the opening statement from the magical 1987 book For an Architecture of Reality written by Michael Benedikt.

Many years ago, I stumbled upon this intriguing little book in San Francisco, in a bookstore devoted to architecture. Somehow, amongst the plethora of larger, alluring books for sale this lightweight gem caught my attention. Its soft, gray textured cover with a mysterious monochrome image and curious title somehow pulled me in more than the latest flashy monographs.

In the preface, Benedikt used “kerchunk” to describe the sound a new car door makes when closing, the sound and feel of something so normal and inconsequential, yet evocative of something special and fresh. For me, finding this book was that kind of the moment, the instant when my world of architectural design was profoundly made new. It has been my north star ever since.

Upon hearing of Benedikt’s recent passing, I immediately felt compelled to find an outlet to express my appreciation for his book and to delineate its brilliance. I am immensely grateful to Texas Architect for granting me this opportunity to compose a piece dedicated to his masterpiece. I was both delighted but intimidated by the task I had so eagerly requested. After struggling with what approach to take, the path became clear—simply use the book itself as inspiration.

Now out of print, this seminal work deserves to be reintroduced to a younger generation and to those unaware of its existence. My second goal is to remind those who already appreciate it how powerful and even more relevant the ideas within remain today, perhaps even more so than when it was published. Hopefully, you will find a copy somewhere or pull it down from your shelf and read it again—and in doing so have your own personal moment of (re)discovery.

Benedikt humbly calls the book an “extended essay.” On the back cover, one reviewer accurately calls it a manifesto, but I imagine Benedikt was hesitant to declare it as such. I prefer the term tome. Although a tome is traditionally defined as a large scholarly book of significance (more on this later), I would argue that the term is fitting here. Though small in size, the book is grand in scope and depth. The Greek root of tome refers to something that has been cut, a section from a larger whole. I like to think that this little book is the genesis of a greater cause: the seed planted for many designers striving to discover and create architecture that seeks something magical yet remains inherently real.

Before I began composing this homage, I pulled the book from its prominent holder on my bookshelf and read it for the umpteenth time. Each reading reminds me how much thoughtfulness is conveyed in such concise fashion. Like any great book, you can find something new to discover in it with every reading. It is an architectural poem, using a haiku-inspired efficiency to describe something both beguiling and sublime. Every page is a revelation. Now, when I read it, I find myself laughing more, appreciating Benedikt’s scathing take-downs of the buzzworthy designers of the time. His commentary obliterated certain dogmas of the current design world and remains just as effective at showing the failings of contemporary design-thinkers who attempt to advance ideas brimming with hubris and a lack of realness at their core.

Realness, as Benedikt describes it, can be summarized in a single phrase: “the evident rightness of things.” Simple as that. It must be a physical thing (not just a building). It must be right (not just feel right). And these truths, he asserts, will be self-evident—recognizable and appreciable by anyone.

He identifies four components that form the foundation of realness, the last of which has two parts: presence, significance, materiality, and emptiness₁ and emptiness₂.

Presence is best illustrated through Benedikt’s example of an actor who possesses stage presence. There is simply more—something palpablein comparison to others. It is an innate quality that draws us in, commanding our attention. Another key point is the unapologetic nature of the element itself—the person or object claims their physical space without hesitation. From the moment it is placed, it belongs there. Although this quality may seem mysterious and hard to pinpoint, we have all witnessed this presence, not only on stage, but in objects and buildings as well. Benedikt writes that buildings with presence “shine” on their own merit but also wait for our presence in return, forming a symbiotic relationship of shared existence.

Significance, in Benedikt’s argument, is deeply personal. To be significant, an object must be important to someone. A key distinction he makes is that it is absolutely not a signifier of something like a movement or theory, etc., but rather a heartfelt significance felt in the soul. It carries weight and meaning, grounded in sincere emotion and connection to the physical world. This book has served as the textbook for many design courses I have taught, even inspiring one graduate studio titled For an Architecture Studio of Reality. It was a pleasure to introduce students to Benedikt’s ideas and challenge them to grapple with their implications. Beyond teaching, the book has remained significant to me, its influence unwavering throughout my entire career.

Materiality refers to the physical traits that define an object and its material clarity and authenticity, or lack thereof. I particularly appreciate this section, as Benedikt acknowledges that it is an increasingly thorny topic. The advancement of faux materials that mimic others has become so sophisticated that they can easily fool the observer. Yet once you realize something is not what it appears to be, it forever becomes a weaker substitute for what was truly desired.

I also value Benedikt’s acknowledgment of the dilemmas we face in construction practice. We must strive to be “material enough,” as the very act of building requires a complex web of materials that is inherently full of obfuscation. His proposed rejection of fraudulent materials has surely caused more than a few eye rolls from contractors, but I believe in this principle. In a world where truth and authenticity seem increasingly vulnerable, it would be profound if we could trust our built environment to truly be what it appears to be. And it is time to extend this aspiration to our personal relationships as well. A realness of materials—an inner substance and authenticity—is both a dire necessity and a meaningful reward, whether in things or in people.

Emptiness₁ and emptiness₂ are, as Benedikt describes them, the most elusive qualities to articulate. The key to understanding emptiness lies in recognizing that the term is not meant in a negative sense, as its typical definition might suggest. Rather, it refers to an inner silence—a state free of intention or imposed meaning. Buildings, Benedikt reminds us, do not have the ability to transmit agendas or convey some mystical musings of the designer’s intent. What you see (as well as feel, touch, smell, or hear) is what you get—and that is enough! It is the task, even the duty, of the inhabitants to be curious, not passive. Meaning arises through one’s own perception and intuition; it is the individual who gives a place its personal resonance and value. It should not be the charge or quixotic ambition of the architect to impose a fixed interpretation or embed symbolism that demands decoding. How arrogant to think that we have the power—or the right—to assign universal meaning to our designs, to dictate how others must experience what we create.

Emptiness at its core acknowledges that human interaction is a part of the equation and that buildings are innately vessels for our existence and the conduit for experiences. They do not explicitly tell us anything; they allow us to feel at our own will. Why does it seem so many buildings (particularly the lauded and published) are screaming at us and telling us what to see, where to stand and how to react instead of just allowing us to find our place within their context. Let there be emptiness; let us fill the space.

In summary, the book reveals its prophetic quality and enduring relevance when Benedikt writes, “In our media-saturated times it falls to architecture to have the direct esthetic experience of the real at the center of its concerns.” That media saturation has only grown exponentially in the 38 years since the book was published, making his call to action even more urgent today. In the age of AI and other machine-generated design approaches—technologies seemingly intent on separating us from reality—we must strive to seek out, understand, and create a world that real people can engage with and absorb to their core, rather than attempting to fulfill ourselves in the ether. In the cloud-based, cyberworld we now inhabit, it is vital that we resist being further drowned in imagery and artificial ___________ (fill in the blank).

I opt to live in reality, with buildings of reality.

Darwin Harrison, AIA, has a one-person firm in Austin and strives to design buildings with realness.

Also from this issue

Housing Policy and the Quest for Shelter

A new model for neonatal care

Austin’s Stealth House defies convention.

The making of El Paso’s Temple Mount Sinai

A bustling community center for Northwest Austin

Exploring new possibilities for green burial

A new home for a West Texas church

The first phase of UT Dallas’s new arts complex revealed

Empathic Design: Perspectives on Creating Inclusive Spaces

Elgin Cleckley, NOMA

Island Press, 2024

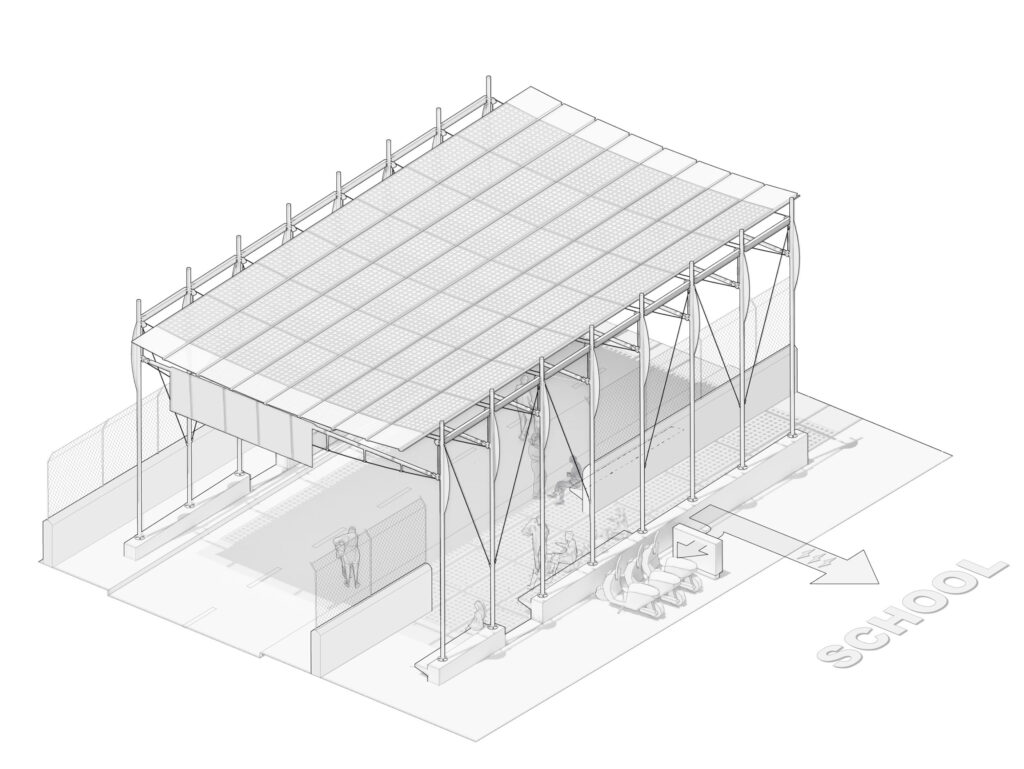

Creating the Regenerative School

Alan Ford, FAIA, Kate Mraw, and Besty del Monte, FAIA

Oro Editions, 2024

Hoping to reach Darwin.

Darwin, Michael would be happy to know that this first book continues to inspire and guide you. How I hope that For An Architecture of Reality will find another publisher and inspire a third generation of architects and designers. I believe that Michael’s final book takes 2 of those qualities of realness even further. In Architecture Beyond Experience, I think Michael has explained both the empirical and ethical nature of what he once called Presence and Significance. Both his first and last books are now out of print and many would love to see them published again. Especially me, Michael’s wife, Amelie Benedikt

I encountered For An Architecture of Reality in the late 1980’s as and antidote to architectural practice playing hard with styrofoam a couple years before becoming Michael’s student in post-professional edcuation. Working with him was one of the primary pleasures of both my intellectual and experienctial life. I now teach using the book to awaken architecture students to the value of the direct esthetic of the real as an antidote to their media-saturated and digital world in hope that Michael’s visual prose can call them toward an architecture of direct experience and also worth spending their lives devoted to producing it. I hear his voice in much that I do. I often pause during my teaching to silently thank him.