Assembly of a Temple

The making of El Paso’s Temple Mount Sinai

I will lift up mine eyes unto the mountains.

— Psalm 121:1

Some 25 years ago in El Paso, members of the congregation of Temple Mount Sinai talked about moving to a more suburban location. This would be the Temple’s third synagogue in its more than century-long presence, each one farther north and west from the center of town. Farther out, there was a new high school, new homes, and new families, and a new synagogue could be somewhat smaller than their current 50,000 sf. It would be manageable—no longer the test of patience their 1960s synagogue had become, which left the congregation weary from worry over its upkeep. Their midcentury building required extensive physical plant and envelope renovations, program reconfigurations, and undoing the flotsam of maintenance-oriented decisions made over the years. Sound reasoning pointed to a move, but it would be a difficult decision because of what they would be leaving behind.

The year 5722 in the Hebrew calendar (1961–62) was a banner year for midcentury modern. By this time, the paradigm shift to modernism—originating in Europe and carried to East Coast academia—had been fully embraced on the West Coast, where California modernists iterated upon it through a culture of expansiveness, single-family lots, and carefree expressionism. In 1952, members of the board of Temple Mount Sinai, El Paso’s then 54-year-old Reform congregation, decided it was time to build a synagogue that would define their next era. By 1961, Temple Mount Sinai’s main sanctuary, school, and offices were complete: a westward-pointing monument, both formally and ideologically, and the culmination of decades of modernist thought. Art and architectural historian Samuel Gruber calls it “one of the benchmarks of modern synagogue design.”

El Paso has long resonated with California culture as much as it has with anything in the heart of Texas, so it was not unusual that the synagogue’s architect, Sidney Eisenshtat, was from Los Angeles. To the rest of the world, El Paso may seem an unlikely outpost for zeitgeist architecture, but it was an attractive site for late modernism in much the same way Palm Springs was—the desert mountain landscape aligning with a love of sunny California culture and the design it engendered. Young generations emerged from rite-of-passage summers spent at California beaches and camp in Malibu with different sensibilities than if they had spent that time in Central or South Texas. They embraced California’s contemporary culture—the untethered spirit and ease, along with the precociousness of LA.

Eisenshtat designed his first synagogue in Los Angeles in 1951, and another in 1956, just ahead of Temple Mount Sinai’s schedule. By the time he began work on Temple Mount Sinai, Eisenshtat’s own life reflected the westward progression of modernism. His family had moved from Connecticut to California in the 1920s, and he graduated from USC’s School of Architecture in 1935, when the program was steeping students in Bauhaus and Abstract Expressionism. His early work showed loyalty to the International Style and Erich Mendelsohn but gained a more self-assured expression as he entered his 40s. He attended his own synagogue in Beverly Hills daily, and one can imagine that this practiced devotion enriched his gift for synagogue design. Equally formative was his immersion in the Los Angeles modernist scene, among a constellation of designers including Charles and Ray Eames, Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler, Gregory Ain, Pierre Koenig, Craig Ellwood, A. Quincy Jones, John Lautner, and Raphael Soriano.

There is hardly a better mark of midcentury pedigree than a snapshot taken by architectural photographer Julius Shulman. As the class documentarian for the heady excitement of the West Coast architecture scene, he had grown into the second wave of modernism in tandem with Eisenshtat. Eisenshtat graduated from USC a year before Shulman received his first assignment—to photograph Neutra’s Kun House. Twenty-five years after that historic shoot, Shulman traveled to El Paso to photograph the novel midcentury work gaining attention there. His El Paso photographs capture a meditative, sensuous, and monumental place, and they are prolific in midcentury modern anthologies—perhaps owing to the dramatically appointed desert mountain sites where the style looks so perfectly at home.

For the Temple Mount Sinai site, seven and a half acres above a residential street in a Franklin Mountain pass were selected after a false start along Mesa Street, El Paso’s major boulevard at the time. Eisenshtat had already provided the Board of Trustees with a schematic design and rendering for the first, more commercial location. He groused about the change but soon saw that the new site offered a theological resonance he had pursued in two earlier synagogues: the metaphor of the desert tabernacle, a tent built by Solomon. Eisenshtat’s emphatic expression of the tent on this site is a parabolic arch that rises like a sail 80 feet above the Temple’s main sanctuary and bends westward with the sunset. Its west wall is made of glass but sheltered, because the arch bows downward, delaying sunset inside the sanctuary.

Behind the site, flow paths and the mountain slope’s rocky topography work in concert with Eisenshtat’s composition—a procession of changing directions and viewpoints, like a cubist collage. From above, the site plan could resemble a Kandinsky or a Bauhaus study, or read as a metaphor for pilgrimage and the search for God. Yet, more matter-of-factly, it bears the imprint of Eisenshtat’s peer relationship with landscape architect Garrett Eckbo. Eckbo had studied directly under Walter Gropius at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the late ’30s and had written the modernist manifesto Landscapes for Living just 10 years earlier.

Taking to the site with his signature poise, Eckbo designed multiple small gardens and monoculture groves of Aleppo pine, Himalayan cedar, and Italian cypress. He placed boulder outcroppings around the site and girded the buildings with rhomboid planters and a sculptural garden pool before the foyer. He also designed an interior garden—later removed by committee, to Eisenshtat’s consternation. Eckbo was on a mission more than a commission; his airline fares, though reimbursed by the board, exceeded his modest fee, and he requested no per diem. The site itself, however, bears witness to a deep and influential relationship with Garrett Eckbo.

Irving Schwartz—a successful El Paso merchant, artist, and temple elder, and the board member who served as the owner’s representative—shepherded the project as a highly collaborative effort. The design and construction team included the El Paso modernist firm Carroll and Daeuble, which facilitated much of Eisenshtat’s work and produced the complex technical drawings. The contractor, R.E. McKee Construction, was at the time also building the iconic LA Airport tower for Pereira & Luckman. Schwartz and Eisenshtat brought in artists early on, viewing artwork as integral to the story the buildings would tell. Five percent of the budget was reserved for the Brutalist works of Taos metal artist Ted Egri and the vanguard glass artist Jean-Jacques Duval.

Eisenshtat had spent decades developing the ability to orchestrate a team like this—and to make it look like kismet. In this El Paso project and its contemporary, Sinai Temple on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, Eisenshtat achieved a cinematic quality, an attribute not lost on Hollywood. His Wilshire Boulevard temple is currently a stage set for Nobody Wants This, the Netflix rom-com about the tension between institutional expectations and modern choices. Eisenshtat’s temple on Wilshire and Temple Mount Sinai in El Paso present the architectural promise of both.

Temple Mount Sinai’s congregation knew they wanted their new home to embody continuity but also to be a revival of nothing before it. Early in their search for an architect—perhaps after seeing the rooflines at Dulles and JFK or the St. Louis Arch—they reached out to Eero Saarinen, who politely declined the commission, leaving the temple with nothing more than a piece of his iconic stationery. Perhaps deflated, and upon the advice of Carroll and Daeuble, the board then exercised more predictable solicitation, reaching out to Percival Goodman, the popular Beaux Arts–educated architect, known to churn out more than 10 synagogues a year. Irving Schwartz swiftly rejected Goodman as a hack, coolly telling the board that Goodman was not “hot as his fee table indicates,” and they moved on with heightened scrutiny.

As the selection process sorted itself out, Schwartz championed Eisenshtat, and an easygoing relationship developed between them throughout design and construction—even amid the pressures of satisfying the board and managing a 40 percent budget increase, which Eisenshtat advised should be covered by a mortgage. In a letter to Schwartz, he argued for the loan, saying it would be a tzedakah—a charitable duty—for the congregation’s younger generation to take on.

Eisenshtat and Schwartz stuck together, affirming nearly every design decision—even those that seemed impractical, such as paving the parabolic arch with one-inch Daltile mosaics. No one would ever see the tiles, with their flecks of color and subtle gradations, but Eisenshtat insisted on them—another means to achieving the retinal perception of light and form he was perfecting with this project.

Schwartz protected Eisenshtat’s design agency at nearly every step, at times quietly allowing him to be ungovernable. At one point, the temple committee asked Eisenshtat to remove glass from a wall of the sanctuary, but he doubled down and redesigned the wall so that its structure depended on the glass—a reversal of material precedence. “Because nothing but glass would give the same effect, nothing that I know of would be good design,” Eisenshtat cautioned Schwartz.

The resulting glass sanctuary walls are immersive and enigmatic, engaging refraction as much as transmittance. They illuminate the pews with thick panes of cyan and tangerine set within trapezoidal perforations in thickened concrete walls—like the sides of a joyful fortress, or as if Louise Nevelson had a sherbet phase. In the small sanctuary, concrete panel walls arch open and move behind the Ark, filled with Duval’s rough-hewn glass blocks laid freely, without gridlines, in a coarse mortar mix. On the exterior of this sanctuary, the glass blocks appear flat—a deep, grayish plum with no hint that light could possibly pass through—but inside, they project a kaleidoscope of abstract shapes in jewel tones.

Eisenshtat’s architecture draws from scriptures such as Exodus 33:23, which says, “Thou shall see My back, but My face shall not be seen.” The approach to God in Eisenshtat’s work is always indirect. Iconography in synagogues is never figurative, because God is an invisible source. Eisenshtat understood exactly how to take El Paso’s daily abundance of light and convey a mysterious divine presence through its subtraction.

Eisenshtat also exalted God through architectural narrative, but never with obvious moves. Temple Mount Sinai abounds with indirect approaches, off-center perspectives, and non-dominant entryways. Neither sanctuary has an entrance aligned on-axis with the bima. In the small sanctuary, one slips through a narrow overlap of walls and follows a curve, as if entering a seashell. By the time you reach the bima in either sanctuary, you’ve encountered moments of contemplation and serendipity along the way. In the large sanctuary, beyond the bima, Eisenshtat layered glass and form to dissolve the wall plane, and the architecture becomes the notion that there is no end point.

A hymn sung inside the two sanctuaries of Temple Mount Sinai is L’cha Dodi, a Shabbat poem containing the riddle “the last in creation simultaneous with the first in thought,” a meditation on source and the rightful order of beginnings and endings. Shabbat celebrates the close of the workweek’s cycle of creation but also an encounter with one’s source—a time to contemplate what will be created going forward.

Forty years after the synagogue’s completion, it faced an uncertain future as members considered leaving the midcentury site and beginning anew, as they had in the past. Rebecca Krasne, a cousin of Irving Schwartz and a fourth-generation member of the Temple Mount Sinai community, says the congregation chose to stay because of the spiritual power of the architecture, its harmony with the mountain pass, and its deep connection to the history of their families. “That’s the place I want to pray,” she concludes—a message Sidney Eisenshtat and those who created the synagogue would have wanted to hear. For this next era, Cunningham Architects are in permit review with construction documents to repair and renew Temple Mount Sinai for generations to come. The restoration is expected to be completed by the year 5788 in the Hebrew calendar—another high point for midcentury modern architecture.

Laura Foster has been a public sector architect for 15 years and currently practices in El Paso, where she lives in and is restoring the historic midcentury Hilles House.

Also from this issue

Housing Policy and the Quest for Shelter

A new model for neonatal care

Austin’s Stealth House defies convention.

A bustling community center for Northwest Austin

Exploring new possibilities for green burial

A new home for a West Texas church

The first phase of UT Dallas’s new arts complex revealed

Empathic Design: Perspectives on Creating Inclusive Spaces

Elgin Cleckley, NOMA

Island Press, 2024

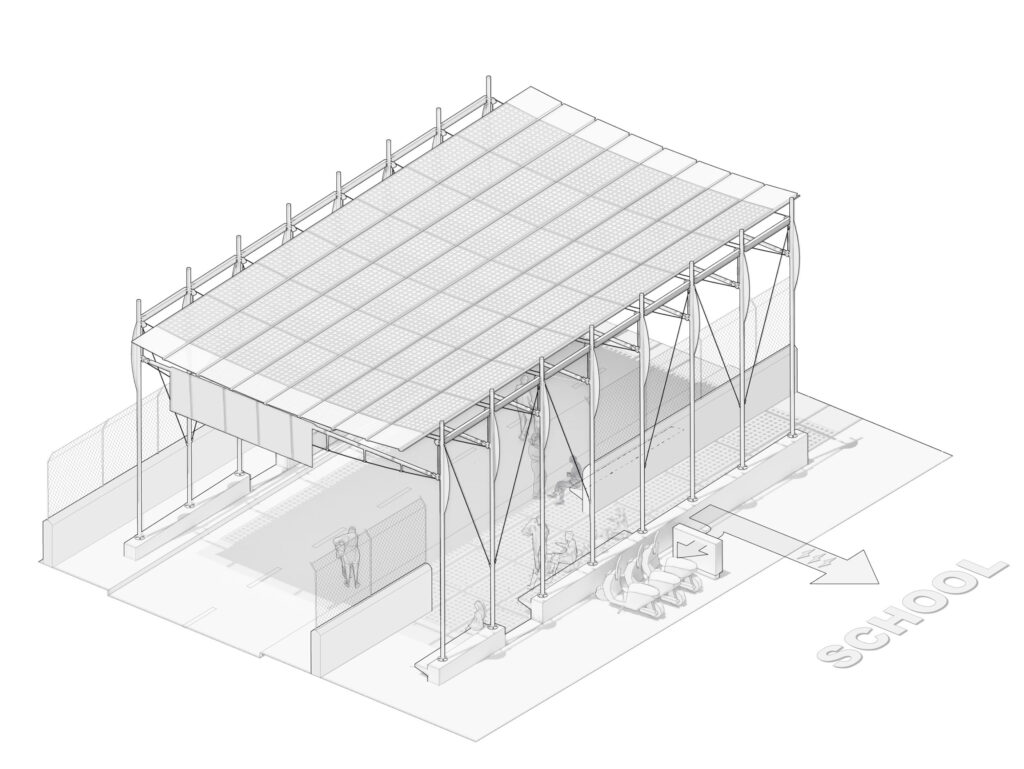

Creating the Regenerative School

Alan Ford, FAIA, Kate Mraw, and Besty del Monte, FAIA

Oro Editions, 2024

A stunningly beautiful temple and school on the foothills of the Franklin mountains. Worth a visit when in the area. Thank you TxA for sharing a Texas treasure.