The Spirit of the Im-Age

Balancing iconic design with more equitable outcomes

In the mid-1980s I had the opportunity to undertake graduate studies at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London. My area of study focused on history and theory, yet that did not prohibit maintaining links to investigations explored in the numerous design units underway in the undergraduate program. Serving as a juror for a student design review, Peter Cook expressed an opinion that caught my interest and has stayed with me: He encouraged students to constantly maintain a “spirit of invention” throughout the entirety of the design process.

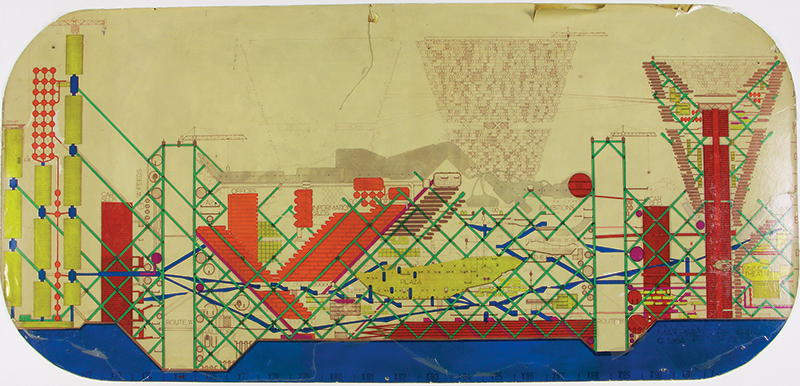

A few years later, I invited Cook to the Hines College of Architecture at the University of Houston to review student work underway in my third-year design studio. During the review, this comment re-emerged; he again urged students to pursue a greater spirit of invention to further animate their work. In terms of illustrating this phrase in his own practice, he certainly had the credentials. He was a founding member of the London-based firm Archigram, which became an icon for many architects and students practicing or studying architecture in the 1960s and 1970s. Walking City, Plug-In City, and numerous other projects suggested directions that combined architecture and technology with the intent of reimagining urban infrastructure and architecture through an enhanced spirit of invention.

At roughly the same time, another architect who was expanding themes for enriching architectural design outcomes was Robert Venturi. In 1966 his book “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” was published, and in 1972, co-written with his wife Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, “Learning From Las Vegas” followed. Both books suggested innovation, if not transformation, as a needed component of the design process. They were understood by many as questioning architectural design directions that had become normative and increasingly predictable, generating ordinary, overly functionalist outcomes that lacked relevance to the general population.

Preceding those investigations was a house Venturi designed in 1964 for his mother, Vanna Venturi. The design positioned itself against these notions of invention, advocating instead for design intentions and aesthetic outcomes beyond the planned regularity that dominated much of the architectural production of that time. Venturi argued for a “messy vitality” of the built environment — an approach allowing for the commonplace flukes and coincidences of life to be reflected in both the design and the design process. In the Vanna Venturi house, both complexity and contradiction were explored as agents of change, though not necessarily as radical as the transformations promoted by Archigram. For Venturi, whether or not the architectural design outcomes were considered conventional, they represented a design aesthetic more agreeable and knowable at the “Main Street” level of appreciation.

Though distinct in approach, both visions for new architectural formulations incorporated a spirit of invention intended as a reaction to the ordinariness of much of the architectural production of that time. In the 1930s, the poet Ezra Pound issued the dictate to “make it new” — that short phrase succinctly capturing much of the modern spirit. In this statement, Pound implied that he and his contemporaries had a responsibility to lead their age, to transform it, and that pushing forward with the new brought with it an underlying opportunity or obligation to advance society through invention.

For architects and architecture, the iconic modern buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier became the early standard-bearers of “making it new.” However, in constantly making it new, inevitable dissonances arose. With a constantly evolving “newness,” a slow detachment from societal content (or conventional cultural meaning) and needs occurred. The “new” became more directly related to distinct architectural positions, each generating individual formal languages.

By the 1960s and 1970s, with the passing of Wright, Mies, and Corbu, the question of “What’s next?” began to emerge. The avant-garde architectural world in the United States became temporarily cleaved between the “Whites”(New York-based architects Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, and John Hejduk) and the “Grays” (Charles Moore, Jaquelin Robertson, Robert Venturi, and Richard Weinstein), with the architectural productions of the Whites tending to substantiate the value of transformational approaches and the work of the Grays leaning toward more subtle modifications. However, the beliefs of both groups represented changes that were increasingly defined less by cultural forces or societal necessities and more as commentaries on culture — or, more accurately, as representing commentaries on architectural production. Output and image, to an extent, became grounded primarily on form- or aesthetic-based inventions, with “content” often fixated on generating answers to the “what’s next” question.

The spirit of invention thus became more of a metaphor for originality within the profession, with “what’s next” being tackled — even still — through succeeding short-lived eras defined largely by formal explorations. Postmodernism, deconstructivism, parametric computer-generated modeling (dubbed “blobitecture”), along with today’s more graphic-based exploration (at least in academia) of inventiveness defined by the term “post-digital,” continue the phenomena. Diverse architectural outcomes and trends represent an underlying ethos that is continuingly defined by a spirit of invention and the implied role of transformation (or “improvement”) rooted within.

Focusing design efforts on avenues that explore new and ever-expanding manifestations of form and originality, along with the associated media interest in the same, has produced notably stunning outcomes that often have coalesced into modes that have become self-defining movements. By the 1990s, Neil Denari could label the architectural production at the end of the 20th century as the “Nike Period” by refashioning the Nike tag line “just do it” to describe the highly exploratory and largely formal explorations of leading architects. Questions arising from this approach are: What is the relevance of continued form-based transformations, and perhaps more importantly, should they continue?

Can we see the spirit of invention differently? Are there topics that could expand that spirit, and if so, what would frame them? Is there a role for design approaches — and aesthetic content — that are more grounded in cultural linkages versus architectural ones? Has an interest in novel, formally driven architectural outcomes passed, or are they a prescription representing a cultural need for newness?

Is there a benefit for the inventive spirit to inform architectural production and representation that addresses the needs of and establishes meaning for broader user groups? Are architectural outcomes possible that are relevant to and can be enjoyed by many types of people? And can these outcomes incorporate both design invention and references to buildings and public spaces that we collectively aspire to, in a celebration of place, culture, and inclusiveness?

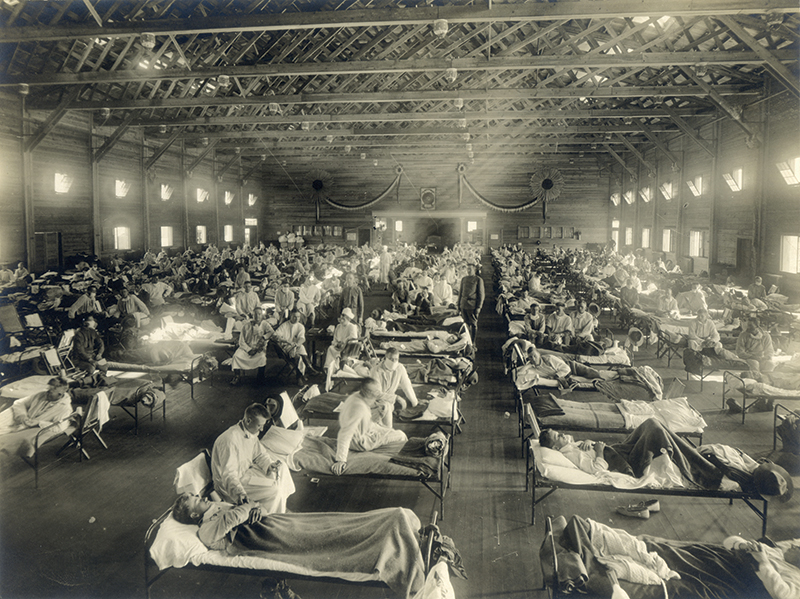

This issue of Texas Architect questions the impact of form-driven approaches to architectural design and their role in society, and, indeed, new and important conversations regarding their contribution to the built environment have arisen. Growing issues of multiculturalism, sustainability, inclusion, and other social equity-based concerns now suggest an architecture less driven by novel design interests and more oriented toward themes of continuity and inclusiveness — a “spirit of convention,” we could say, a use of architectural forms and language more widely recognized and understood by broader society. With its likely allusions to pre-modern or classical architecture, convention is a term that no dyed-in-the-wool modernist would accept; however, informed convention could leave room for innovation.

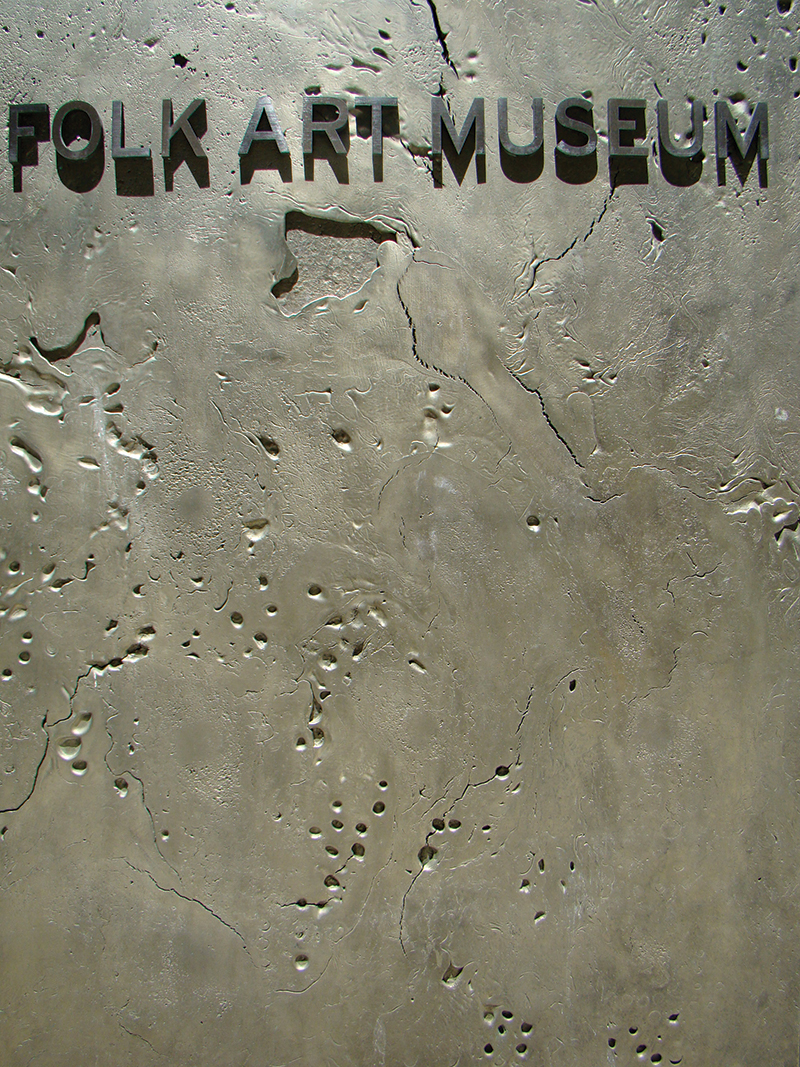

The term “informed” implicitly addresses the issue of content and suggests that we may already be surreptitiously traveling on the road to enriched architectural production. Three “accessible” types of content come to mind — that is, architectural designs that appeal to and hold meaning for a broader swath of society. The first is arrived at through a conceptually strategic use of materials. Instead of simply being considered in terms of their function, materials and their organization — when understood as something representational — can convey more associative meanings that many can understand, regardless of the design itself. This concept is illustrated in the early work of Morphosis. A largely pre-Morphosis world of steel, glass, and concrete cladding finds its counterpoint in almost Venturi-esque fashion in the firm’s 2-4-6-8 House of 1978. Eschewing modernist and minimalist norms, the house employs a tin hip roof, asphalt shingle siding on its walls, and a white picket fence in an architectural language that was detailed, according to the project description, “in a form any layperson could comprehend.”

Morphosis followed the 2-4-6-8 House with the Kate Mantilini restaurant in Beverly Hills in 1986. While no doubt “modern” with its simple and delicate Miesian exterior frame, it is hardly modern in the same vein as Phillip Johnson’s legendary Four Seasons Restaurant in NYC. The design pays a graphic homage to pugilism and also includes a tectonic orrery linking the solar system to a “constellation of elements,” its material choices suggesting a modern design language comfortable with a broader set of references. It is not a stretch to connect the material expressions of these projects to the subsequent material-rich explorations of numerous other architects who have sought to downplay early modernist focus on an abstract expression of points, lines, planes, and masses.

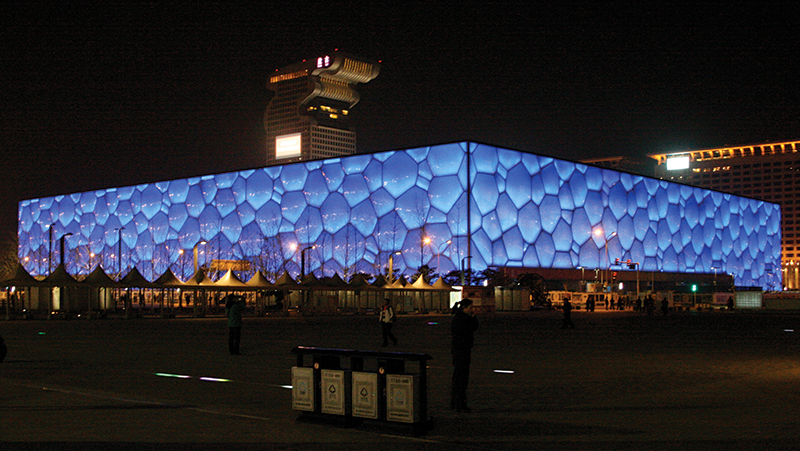

Secondly, by the time we move past the “Nike Period,” another framework of images based on a spirit of invention arises, expressing the potential to advance Venturi’s desire to deviate from the planned regularity of early modernism. Hardly representing “informed convention,” directions identified in the work of PTW Architects, Santiago Calatrava, Kengo Kuma, Peter Zumthor, and others suggest design aesthetics that, when removed from their more iconic expressions, reveal the complexity, diversity, and plain old quirkiness of humanity. When considering architecture’s ability to elicit emotional responses and connections to themes beyond immediate functional needs, these types of projects may connect us to such oh-so-human experiences as mystery, anticipation, and surprise. This is something that modern architecture has not always done successfully, but that people often enjoy in walkabouts through vibrant older parts of cities.

Lastly, issues surrounding climate change should be an absolute content driver for more informed and relevant outcomes. However, the first goal should not be the creation of high-performing sustainable prototypes, such as solar-clad buildings or a new kind of water purification plant (no matter how valuable such advancements may be), but rather the simple implementation of passive design strategies. Passive design inherently draws upon architectural forms rooted in humanity’s oldest building traditions — approaches employed in building design almost exclusively until about 100 years ago. An icon for the spirit of convention should include fundamental architectural elements that shelter and shade, whether through offsets, overhangs, layers, or shading devices.

While the three approaches outlined above represent steps to a spirit of inventive convention that might frame aesthetic directions that are more understandable rather than iconic, do they capture the current spirit of the day, or do they simply represent easy inclusivity? Do the themes address topics related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, exploring new and uncharted territory for a profession enamored with norms defined by the spirit of invention? Is a spirit of inclusive diversity, both cultural and architectural, required to move beyond where we are? Inclusion versus objectification represents a possible theme to propel our approach to invention forward.

The spread of our cities and the concomitant objectification of buildings based on automobile-oriented land development is well recognized. Repurposing existing areas of our cities without relying on formal iconography or objectification might permit a messy vitality that is both familiar and comprehensible to the general public, advancing the potential of the topics outlined above. However, gentrification and the burden of increased tax rates that has befallen neighborhoods adjacent to projects like the High Line in New York City suggest that creating a richer urbanism might not actually be inclusive. In that project, diversity and inclusivity have suffered as increased property values displace long-term residents and businesses and replace them with thousands of tourists flocking to a new and “original” creation. So what to do?

Let’s rely on the spirit of invention, but a version founded on listening carefully. Programming was an architectural sub-practice that gained momentum in the 1970s. The principles of programming still apply today, but the emphasis must shift from addressing organizational needs to a process that explores, expresses, and builds upon the values of marginalized communities. Listening is needed at all levels — from architects and developers to government leaders — to ensure that values and needs of clients, especially those from marginalized groups, are accurately documented and reflected in design rather than simply assumed.

To avoid outcomes like the displacement that befell the High Line neighborhood, it is necessary to protect and maintain existing community anchors — or else to appropriately design new ones. This could take several forms, including: building affordable housing through designs that incorporate images and aspects of dwelling versus housing (neighborhoods that include freestanding residences with rental cottages to the rear, townhouses, duplexes, and well-designed and -scaled multifamily housing should all be considered); reprogramming (and ultimately redesigning) schools to become flexible after-school community spaces that both assist working parents and lend a sense of permanence and harmony to neighborhoods; and creating open-air markets that mitigate food deserts and become iconic hangouts specifically because of their messy vitality rather than their architectural form. Reflecting shared values through an inventively designed yet “messy” architecture could be of great value to sustainable community development by strengthening community bonds.

Another image to be evaluated may be that of the profession of architecture itself — can it come to encompass expanded connections to and more inclusion of user groups? There is no doubt that improved partnerships are being made, but both the reality and image of the profession is one in which architectural designs have largely been envisioned from a single point of view by those with relative privilege and access.

It is unfair to say that design movements advanced in recent years — whether promoting sustainability, pedestrian-oriented towns and cities, or other similar enhancements — are less important, but they do emanate from more singular, and often privileged, perspectives. Deeper connections with those who have “walked the walk” would allow the profession to balance work between the creation of iconic images and a more equitable addressing of basic needs. The good news is that, in part, this is already occurring. At the University of Houston Hines College of Architecture and Design, the make-up of those seeking degrees in architecture represents a balance of 46 percent Hispanic, 7 percent African American, 15 percent Asian, 21 percent Anglo, and 10 percent international/other. These numbers represent the potential for the next generation of architecture and architects to be driven less by viewpoints derived from a privileged perspective of users’ needs and instead from a keener understanding based on lived experience.

The architectural outcomes and images of the future may indeed have a broader reach if they are not prioritized by the spirit of invention and instead champion a spirit of inclusion — one allowed to percolate continually and, fittingly, focused on reflecting an informed and inventive spirit of convention. While it is likely that a spirit of invention as it has been historically defined through formal exploration will remain, a modification of design methodologies allowing for a richly informed convention could provide improved content-making. This can be accomplished by employing design strategies that start with predesign conversations and include, as Susan Rogers (director of the Community Design Resource Center within the Hines College of Architecture) posits, asking big questions and listening to the answers. She states that the big questions provide answers that are more relevant since they explore possibilities, whereas answers provided to more normative questions often reflect expectations that are envisioned by others.

Another suggestion Rogers offers relating to reimagined and revitalized outcomes has to do with programming and improving its use in the form of post-occupancy analysis. Undertaking this analysis could provide a clearer understanding of which architectural decisions, whether programming-based or spatial/formal in nature, assist in creating a body of information that allows architects to become more cognizant, empathetic designers. Maybe a new post-occupancy “Learning From …” evaluative process — not far removed from what Venturi undertook in Las Vegas — would provide valuable insights and point toward informed conventions whose effects are enjoyed, respected, and understood more broadly. Solutions that meet community needs but that do not create destinations promoting rapid gentrification may represent architectural outcomes that become iconic because they offer a gradual evolution of space that brings value to their neighborhood by instilling meaning and acting as a financial lifeline. The relevance of images for the near future may be in the realm of designing exemplary urban — even suburban — places that underscore universal values — places in which hanging out, being with family, and having an improved sense of stability and order in our lives is seen as the most noble outcome. Making it new may not always be the desired result, but working with a reimagined spirit of convention might just be all right. Maybe we can “just do it.”

Tom Diehl is an associate professor at the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design at the University of Houston and a practicing architect. He recently published a book entitled “Internal: Developing Informed Architectural Languages.”

Also from this issue