Healing a Broken System

How society views those experiencing mental health issues — and the facilities architects have designed for those individuals — has changed over time.

“People with mental illness are our neighbors. They are members of our congregations, members of our families, they are everywhere. If we ignore their cries for help, we participate in the anguish from which those came. A problem of this magnitude will not ‘go away.’ And because it will not go away, we are compelled to take action.” — Rosalynn Carter, Former First Lady, 1979 Presidential Commission on Mental Health

Recent years have seen a renewed public interest and education in mental health. Sobering statistics are communicated by the media and politicians alike, while the global pandemic has brought the reality of mental health challenges into many people’s homes. Yet many working within the long-ignored and broken mental health care system feel as though they have been shouting into the void for decades.

For a system serving some of the most vulnerable among us, the stakes are very high. Mental health treatment can be lifesaving, and the physical environment can support a better quality of life for practitioners and patients alike. However, there is a long and complex history of both success and failure in the alignment of design and patient care.

There is promise at the end of this decades-long cycle of progress, setbacks, and breakthroughs which are informing the design of an unprecedented number of new facilities nationwide. In 2020, the American Society of Healthcare Engineering stated that 40 percent of the specialty hospitals under construction were for psychiatric and behavioral health. Since 2019, the state of Texas alone has invested $745 million to improve its psychiatric hospitals. Mental health practitioners, policymakers, and designers are collaborating to learn from the past, while also studying the present, to effect a better future.

A Brief Early History

Prior to the 1800s, most people experiencing mental illness were punished and confined. The 19th century saw the establishment of isolated “asylums” — quiet, secluded, peaceful country settings where individuals were protected from the stresses of society. This model, also known as “moral treatment,” led to the development of the Kirkbride Plan in which no more than 250 patients lived in a building with a central core and sprawling wings arranged to provide daylight and fresh air. By the 1870s, virtually all states had one or more state asylums, such as the Austin State Hospital, which opened in 1861 as the Texas State Lunatic Asylum.

By the end of the century, economics had driven local governments to redefine senility as a psychiatric problem in order to send elderly residents to state-funded asylums. As a result, the number of patients grew exponentially. This strained the system, resulting in overcrowding, disrepair, and mistreatment. The promise of “moral treatment” also confronted the reality that many patients — particularly if they experienced some form of psychosis, trauma, or dementia — either could not or did not respond when placed in an asylum environment.

Further exacerbating the issue came the economic crises of the early 20th century, resulting in cuts to state appropriations and acute shortages of personnel during the Second World War. A series of exposés in the 1940s drew attention to the inhuman conditions of many state hospitals, but they also damaged recruitment and increased the social stigma surrounding mental health issues. By the middle of the 20th century, due to their physical features and geographic isolation, asylums were revealed to be facilities for confinement and surveillance, with depressing wards and crowded dormitories.

A Broken Cycle of Progress

The year 1953 saw the launch of the Architectural Study Project, a collaboration of the American Psychiatric Association and the American Institute of Architects that culminated in the publishing of “Psychiatric Architecture” in 1958. The project influenced both design and the practice of psychiatry, encouraging the field to move beyond the mental health hospital toward smaller and more flexible alternatives as sites for psychiatric care.

Yet successful deinstitutionalization would require robust community mental health programming. State funding cuts reduced the number of beds, sending many patients to newly created nursing homes ill-equipped to treat them. This era of deinstitutionalization was not effectively buttressed with adequate outpatient care and community support networks, ultimately leaving thousands without resources.

The resulting discord at local and state levels meant turning back to the federal government for new outpatient initiatives, and in 1963 the Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC) Act directly funded the construction, start-up costs, and staffing of these outpatient centers and services. But despite increased funding over the next decade, issues continued to hinder the development of a cohesive network of outpatient support to provide for community-level care.

In the early 1980s, the federal government de-funded CMHCs and substituted unrestricted “block grants” to state mental health agencies while simultaneously lowering funding by 25 percent. This further reduced the state hospital populations, again without community-level facilities to replace the loss of beds, resulting in a significant increase in the number of homeless persons with mental illness.

The Tide Turns . . . Slowly

As the 20th century ended, state mental health agencies began moving away from institutional psychiatry and toward outpatient services for the chronically mentally ill. Comprehensive case management, outpatient pharmacological treatment, and supportive psychotherapy increased. Community residential programs added beds, and day treatment programs that focused on psychosocial and vocational rehabilitation expanded. Increasingly, CMHCs were integrated into the statewide systems of care.

Even with these improvements, a Presidential Commission concluded in 2002 that the mental health system in the United States was in shambles. The recommendations of this Commission were frustratingly like those of another study conducted 25 years earlier. Following this report, research increased and environmental psychology gained traction as evidence-based medicine and design emerged as focused methodologies. This renewed attention on the relationship between the physical environment and behavior included studies of mental health environments to generate and test concepts and principles through observation. Architects continued to recognize that mental health environments were critically important because people experiencing mental health issues were especially sensitive to their surroundings, a fact compounded by the reality that inpatient long-term care could last months, if not years.

Multiple organizations began developing guidelines for the design of mental health facilities. The Facilities Guidelines Institute first published a Behavioral Health Design Guide in 2003, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs published its Mental Health Design Guide in 2010. These documented more broadly some of the design concepts already being implemented and tested by architects across the country.

21st-Century Evolution of Care and Design

Today, multiple design philosophies compete for relevance, though many architects in the field are implementing a hybrid of these approaches: Evidence-based design; patient-centered design; generative design emphasizing social interaction; salutogenic, or psychosocially supportive, design that is comprehensible, manageable, and empowering; and, most recently, trauma-informed design, in which supportive environments are designed to recognize individual trauma and resist re-traumatization.

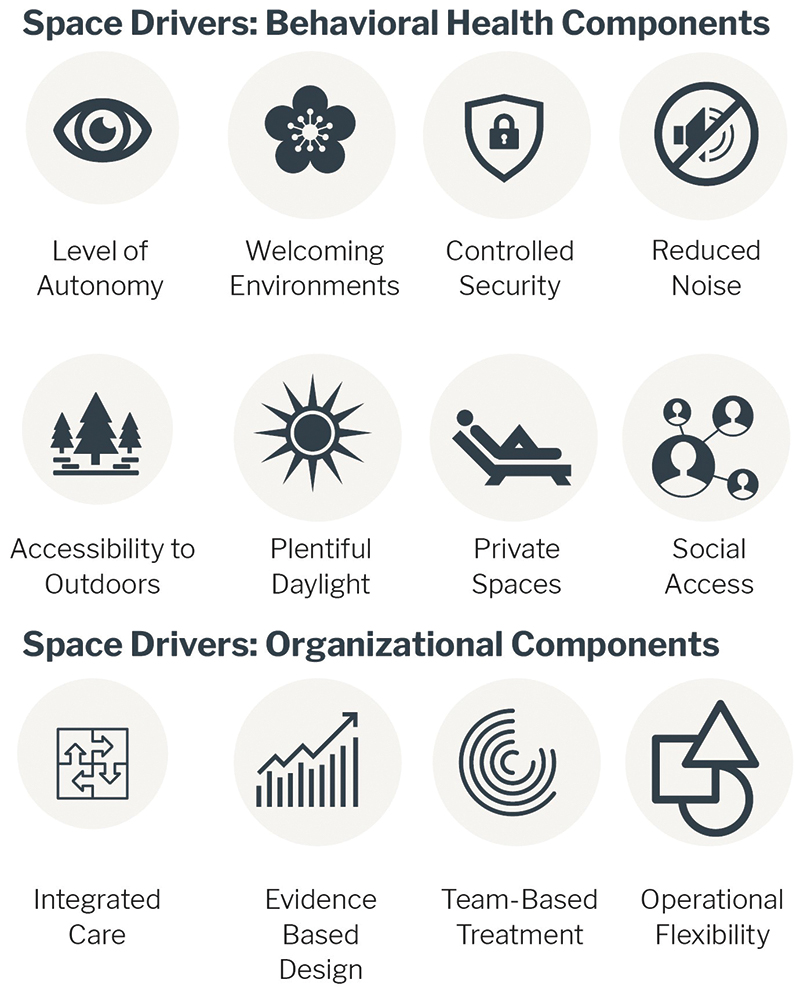

A study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology in 2018 supports the link between the built environment and human behavior. Findings and recommendations include reducing crowding stress by designing single bedrooms with private bathrooms and keeping social density low; reducing environmental stress through improved acoustical design and patient environmental control; creating positive distractions via views and access to nature, art, and daylight; and designing for observation of communal spaces from a central area.

“Look at our state hospitals, which were built decades ago based upon care models that are decades if not a century old. These massive and often isolated buildings and campuses, some of which are in really poor condition, were created for a very different time, and often fail to incorporate modern treatment approaches. They are filled with good people who are inadequately supported working in poorly designed structures. … We have the opportunity to ask ourselves, from the ground up, what a modern mental health care system should look like.” — Stephen M. Strakowski, M.D., Associate Vice President for Regional Mental Health, Dell Medical School

But implementing improved facility design to better support modern psychiatric treatment requires capital investment, something the state of Texas rarely prioritized, leading to the 2019 comprehensive master plan for the Austin State Hospital Brain (Mental) Health System.

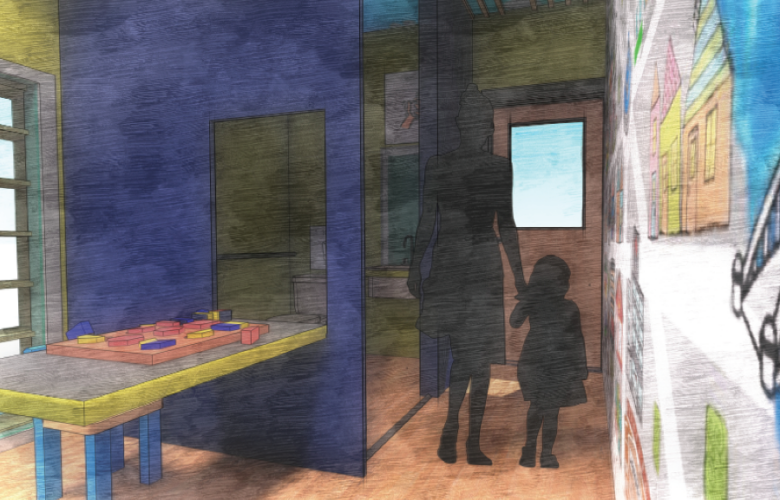

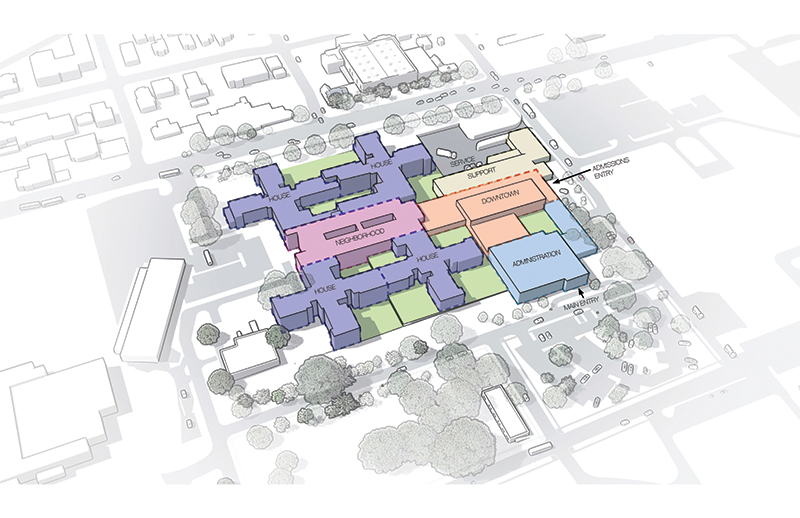

The master plan recognizes the critical first step of replacing and consolidating inpatient facilities on campus with a new hospital, and doing so within the context of developing a comprehensive brain health continuum of care. The new hospital is organized into a house-neighborhood-downtown model, with small cluster-based inpatient treatment settings existing within larger inpatient units. This planning prototype, developed and refined since the 1990s, supports a model of care which endeavors to return individuals to the community and is broadly used in the design of modern mental health facilities.

A primary driver of the design of the Austin State Hospital is to create a sense of connection with the community, encouraging a welcoming environment tied into the contextual fabric of the surrounding neighborhoods. Gone is the 19th-century romanticization of rural isolation.

The most critical factor is to ensure continuity of care for individuals rather than relying on a crisis-only model. Clinical models are evolving, and the availability of quality services along the continuum of care varies widely. The collocation of mental health and primary care can reduce stigma by mixing patient populations, and according to the CDC, by 2010 almost 70 percent of primary care clinics were providing mental health services. This trend will likely continue as the biological nature of psychiatric research, where brain health, neuroscience, and psychiatry converge, has steadily been moving mental health care away from palliative care to active and preventive treatment and intervention.

Remaining Challenges

As tragic news stories indicate, law enforcement often serves as a less-than-ideal entry point to mental health care, while community residences, intensive outpatient clinical programs designed to detect and treat early signs of psychotic decompensation, and high-quality social and occupational rehabilitation programs are in notoriously short supply.

The misalignment of clinical care and law enforcement creates a strain on resources for an already challenged care environment. As psychiatric facilities are often populated by law enforcement whose commitment is at times involuntary, designers are tasked with finding a balance between supporting safety and custodial care for staff, while empowering patients in their own health care. For example, design and technology can reduce the visibility of security measures, and surroundings can be designed to reduce the perceived power differential between law enforcement, practitioners, and patients. But design alone cannot be the only solution. There is a desperate need to disentangle clinical care and legal decision-making.

More than 5 million Texans experience a mental health condition each year, and these numbers have dramatically increased since the beginning of the pandemic. In 2020, the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute estimated that for every 1 percent the unemployment rate increases, an additional 700 Texans could die from overdose or suicide. The Kaiser Family Foundation reported that people struggling with mental health increased from 32 percent in March 2020 to 53 percent in July 2020. We have yet to see the full extent of the pandemic’s impact on mental health, but we have seen an increasing demand for service, limitations on inpatient care, a greater emphasis on crisis stabilization, an increase in infection control measures, and reduced face-to-face visits.

Yet out of the tragedy of COVID-19, opportunities exist as well. Increased use of virtual health tools, including a greater focus on continuous care, medication reminder check-ins, reduction in stigma, greater public awareness, increased collaboration among specialties, and increased family involvement are all steps toward normalizing mental health care while making care more accessible.

There will be no single perfect solution to resolve the fractured mental health care system situation. The explosive increase in renovations and new construction projects for mental health facilities is a promising step toward better supporting practitioners and individuals receiving services. However, it is clear that the mental health care environment must be made up of a comprehensive constellation of services at every level of society to best support prevention, intervention, and treatment and avoid the failures of the past. This will necessitate an unprecedented level of multi-disciplinary focus, public awareness and advocacy, education, training of law enforcement, and consistent funding and accountability from those responsible in order to provide these public health services. Lives and livelihoods are at stake.

Natale Stephens, AIA, is a senior health care planner at Page.

Also from this issue