After the Flood

On August 26, 2017, Harvey dumped one trillion gallons of water on Harris County across a four-day period. All 22 watersheds within the county reached record levels. The storm set a new bar for the most rainfall from a tropical cyclone ever in the U.S., and was the latest in a series of super storms that have forced us to confront how we build cities in coastal regions. (This was going to press as Hurricane Florence bore down on the Carolinas.)

Lisa Dickson, U.S. resilience lead at Arup, says that we need to reconsider how we conceive system change. She breaks it down like this: 1) resetting the baseline for climate change; 2) focusing on both successes and failures; 3) recognizing value capture and return on investment for faster implementation by private sector players.

In resetting our baseline expectations, a report from MIT concluded that, for now, we can expect a 1-in-100-year flood every 30 years. A formerly labeled 1-in-2000-year storm is now classified as a 1-in-100-year storm. Hurricane Sandy was a 1-in-900-year storm and will likely now be a 1-in-20-year storm. In the past five years, Houston endured three 500-year storm events. Harvey alone cost an estimated $150 billion in damage, by conservative assessments, with trickledown effects to the Houston economy as a whole.

There are no meaningful metrics to discuss the value lost in a community’s health, safety, and welfare after an event like Harvey. During and after the storm, many children missed school — the impact on their education is immeasurable. Nearly 20 percent, or 345,000, housing units in Harris County suffered structural damage. It’s estimated that 600,000 businesses suffered large discontinuity. The most disrupted asset class was commercial office space. In the energy corridor, one 14-story office building held less than a foot of water, but full recovery took six months, due to labor and material shortages. The second-most disrupted asset class was medical office buildings, which occupy disenfranchised areas.They have little infrastructure support and little resilience design in comparison to medical centers, which fared well during Harvey. The third-most affected asset class was hospitality, which hosted displaced people, many of whom did not have the means to pay. The fourth-most disrupted business type consisted of not-for-profits and churches. On tight operating budgets often dependent on fluctuating donations, they offered space as temporary shelter and acted as impromptu medical providers.

Harvey highlighted problems with the resiliency of Houston’s infrastructure. For example, local streets designed to act as a secondary drainage system in the event of a major storm were impassable. Getting replacement chemicals to wastewater treatment plants required hovercrafts and police escorts, which took weeks. While medical centers fared well in-place, they were inaccessible to many people who needed them. Major highways were flooded and unusable for weeks. Due to delayed congressional approval, FEMA funds were held up before passing through to the Texas General Land Office and finally being forwarded to the City of Houston for disbursement. So what’s Houston doing about it?

100 Resilient Cities / The Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation created the 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) network in 2013, a $164 million global effort to connect and enhance resilience efforts around the world. Thanks to the sponsorship of Shell Oil, Houston became the 101st participating city on August 29. The foundation provides a framework for planning and design solutions to increase robust system responses. The resilience framework addresses acute shocks like floods, disease outbreaks, terrorist attacks, and earthquakes, as well as chronic stresses like high unemployment, inadequate transportation systems, endemic violence, and chronic food and water shortages. Climate-related shocks are the number one disruptor of normal city activities and services. For cities already experiencing chronic stress, climate-related shocks can be especially devastating.

The 100RC framework brings a methodology for prioritizing building strategies to address both acute shocks and system stressors. The program provides two years’ salary for a chief resilience officer. 100RC provides a platform of over 120 strategic partners around the world who have donated pro bono hours valued at over $200 million in services and information-sharing. The framework does not include a segue for capital investment. Forty-seven of the existing 100RC have released resilience strategies, which contain more than 2,300 concrete actions and initiatives. 100RC estimates that 70 percent of the world’s population will live in urban centers by 2050: We need to build resilient infrastructure now.

The New Orleans-based Water Institute of the Gulf will act as Houston’s principal technical partner in designing a formal resilience strategy. Niel Golightly, chief of staff of the Recovery Office for the City of Houston, says “The best solutions encourage livability, mitigate risk, and increase protection for both current and future uses,” and multidisciplinary designs and solutions are stressed.

Infrastructure / City of Houston

To prevent the severity of flooding in Houston’s office core, the North Canal project looks to divert the swollen curves of White Oak and Buffalo bayous. Steve Costello, Houston’s flood czar, notes the project should lower water in the bayous by two to five feet during flood events. The estimated cost is approximately $160 million, with multiple agencies directly participating and benefiting from the project. The long-term vision includes a revitalization of the pedestrian path for the center of Houston. The North Canal project along White Oak and Buffalo bayous has been on the books for more than 20 years but could not move forward due to lack of financial resources. Now, the project has been submitted to FEMA for funding.

The Ruffino project is another flood mitigation measure that has been on the books for years without financing. It’s a dormant landfill on Keegans Bayou, which could provide relief for downstream areas on Brays Bayou, like Meyerland, that have continually flooded for years. Nearly all Meyerland is located within the 100-year flood plain. Under the new proposal, the City of Houston will dig out the landfill and create a detention pond. Relocating the landfill will cost $200 million, with an additional $50 million required for channel improvements along Keegans Bayou. The city is seeking federal funding to complete the project, which requires coordination with county, state, and federal agencies. “If you get everyone involved, you can maximize the available funding at all levels,” says Costello. “Federal funds require a local share. By engaging all players, it minimizes your contribution at the local level and increases agency collaboration.”

Adopt-a-Drain / City of Houston

The City of Houston, in conjunction with Keep Houston Beautiful, launched the Adopt-a-Drain program in April 2018. This participatory program asks community members to adopt an access drain inlet in curbs and gutters along Houston’s streets, committing to keeping the gutter free of debris and clutter for 10 feet to either side. The goal is to ensure that Houston’s miles of drainage systems can function optimally in storm events. According to Houston Public Works, of the 100 adopted drains surveyed by the maintenance department, 90 percent had improved conditions in comparison to drains not in the program. The City of Houston spends $10-15 million annually in stormwater maintenance. Full implementation of Adopt-a-Drain could substantially reduce operating costs, and improve the quality of water draining into Galveston Bay.

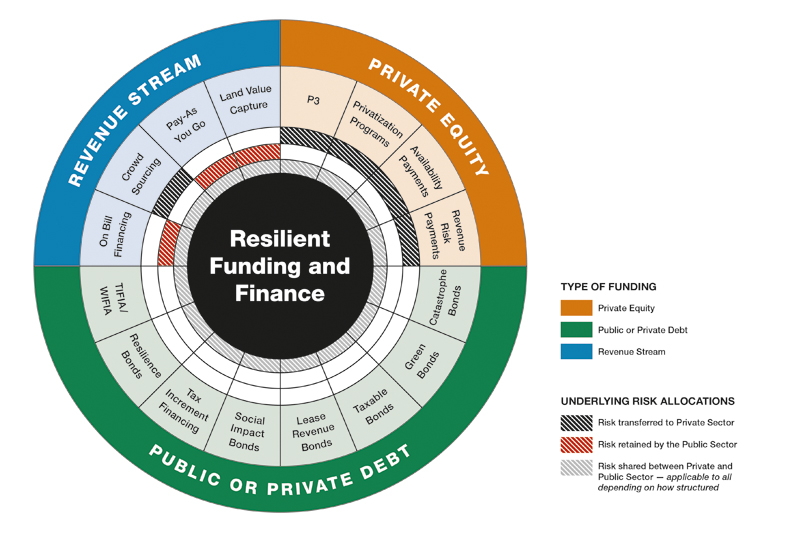

Resilience measures can be a challenging discussion for architects and building owners. In implementing measures, discussion often centers around who will pay for the capital expenditures. Who owns the risk of not being resilient? Who benefits from the operational savings? This graph shows how Arup evaluates financing options among revenue stream, private equity, and debt with a focus on risk transference. GRAPHIC COURTESY RESILIENCE FOR THE AMERICAS, ARUP

IncentiFind

Since building resiliently can reduce long-term risks for property owners, states and municipalities are beginning to offer incentives to those who implement such measures. After years of connecting building portfolio owners and developers with sustainability initiatives at AECOM and Jacobs, Natalie Campos Goodman created IncentiFind, a database of over 12,000 sustainability and resiliency initiatives. The process allows a lender to incorporate sustainability with the cash flow analysis to demonstrate the business case for sustainable, resilient solutions.

One such loan product is CPACE (commercial property assessed clean energy). The program is funded by private investors and government programs, but enabled by state legislatures. In Texas, only existing buildings are eligible for CPACE financing. CPACE allows owners to borrow money for energy efficiency, renewable energy, or other projects against their tax bill. The debt is tied to the building, and the loan stays with the building through transactions.

IncentiFind works with over 500 lenders to create similar financial win-win scenarios for building owners in both new and existing projects. Common resiliency incentive projects include renewable energy, combined heat and power, battery storage, backup generation, microgrid, electric vehicle charging, efficient lighting and HVAC, water efficiency measures, building envelope improvements, wind resistant roofs and windows, and flood mitigation. These loans can cover all hard and soft costs for qualified resiliency projects, providing better terms to improve cash flow impacts for building owners.

During Harvey, water overwhelmed the flood gates of the Wortham Theater. The design and construction schedule for repairs was nine months, indicating an incredibly efficient and cooperative design-build process. PHOTO BY LEONID FURMANSKY

The Wortham Theater / Arup

The Wortham Theater, home to the Houston Ballet and the Houston Opera, sits on the banks of Buffalo Bayou. Harvey overwhelmed the building’s floodgates and water breached the backstage door, spilling into the orchestra pit and the first few rows of seats. In some places, the building held 12 feet of water. All HVAC systems, electrical switchboards and panels, components of the mechanical stage lift, and finishes in flood-damaged areas required replacement. The two parking garages flooded in three subterranean levels. It took five weeks to pump the water out.

Water levels during Harvey climbed more than 38 ft above sea level. In rehabilitating Wortham, Arup and Houston First decided to protect the theater and its garages against floods up to 41 ft above sea level. Tom Smith of Arup says that designers need to consider how a building will handle water once it has breached the interior, as well as how to keep it out. Ventilating bacteria-filled water, protecting equipment, and draining after a breach are all important considerations. Five or six feet of water adds significant weight and could cause loss of structural integrity.

The design was prioritized for 1) immediate recovery; 2) restoration; and 3) mitigation against future events. Submarine doors were added at the Smith Street entrance. Sensor-activated flood gates were added facing the bayou and at the Prairie Avenue entrance. In an ideal scenario, all mechanical and electrical equipment would be moved to the roof, but it was not cost-effective for this project. Instead, the systems were raised internally within their existing basement: The electrical substations were elevated 10 ft and the air handlers 4 ft. The theater re-opened on September 26.

Code Changes / Houston Public Work

Throughout the rebuilding effort, Mayor Sylvester Turner directed Houstonians to build for the future. Houston City Council approved stricter building codes with the intention of reducing flood damage. The mayor introduced measures in January 2017, but city council did not approve them until April 2017 in a 9-7 vote. It was the first modification to the flood plain in over a decade. Within Houston’s Infrastructure. Design Manual and Building Code, the following revisions took effect September 1, 2018:

- Chapter 9: Detention requirements are no longer grandfathered for existing paved surfaces.

- Chapter 13: For infill development, site drainage was formerly allowed to drain through the site from front to back. Now, stormwater cannot be displaced to adjacent properties.

- Chapter 19: Previously, the residential finished floor elevation was required to be one ft above the 100-year flood plain, and homeowners within the floodplain were required to have flood insurance. Now, the requirement will be two ft above the 500-year flood plain. The ordinance will affect all new construction and any home that increases more than 33 percent in square footage.

During Harvey, a third of homes in the 500-year flood plain were damaged by flooding. In the 100- and 500-year flood plains, 84 percent of homes would have avoided damage had the new regulations been in place.

Conclusion

Houston had many successes during Harvey when compared to Tropical Storm Allison in 2001. The Texas Medical Center was able to shelter in place without flooding. Unfortunately, many people had trouble accessing it, which speaks to the need for transportation resiliency. Moving forward, we can expect to see more projects like Partners HealthCare in Boston. They included operable windows in patient rooms that are on timers. They moved all electrical and mechanical systems to a penthouse on the roof, added a boat ramp to the entrance for emergency access during flood events, and added planting and retaining walls to act as a reef against storm surge. Partners reported a revenue of $13.4 billion in 2017. The resilience modifications cost less than .5 percent of their annual revenue. This investment will mean the difference between success and loss of life in the next extreme event.

By offering incentives and financing options for sustainability and resilient solutions, cities and states can address the limitations of today’s codes and zoning while also encouraging the construction of better-protected buildings in the redevelopment of existing properties for higher-value uses. Architects now have a powerful set of tools to discuss such solutions with building owners.

Houston 2020 Visions is a yearlong invitational collaborative process led by City of Houston Council Member David W. Robinson, FAIA, and the AIA Houston chapter. Aptly tied to the Harvey anniversary, the project kicks off August 25, 2018 and concludes August 25, 2019. “As a citizen-architect, I want to help our city consider the best thinking and ideas to help build forward for a better future,” Robinson says. “Mayor Turner has been adamant about not ‘funding for failure.’ As we anticipate recovery funds coming down from the state and federal government, we need to be ready with creative and innovative ideas for how to rebuild a better city.” The program seeks expansive, creative visions for resilient responses, including infrastructure projects, policy recommendations, warning systems, and resilient housing design. Lectures and community meetings throughout the year will conclude with a Call for Visions, to be exhibited at the Architecture Center Houston and released in publication. Who better to design the next wave of resilient futures than Houston architects?

Jen Weaver, AIA, is an architect and developer in Austin and Los Angeles.