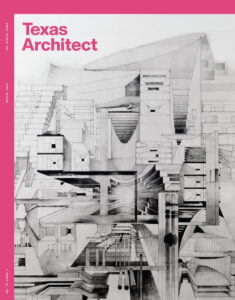

Abstract Arch: Architecture as Art

The Blanton Museum of Art in Austin has constructed on its grounds an ambiguous building designed by a giant of the contemporary art world, Ellsworth Kelly. Originally conceived in the mid-80s, during the fever pitch of the postmodern era, it is the first and only work of architecture by the late artist. The building, sited away from the two existing museum buildings, is presented as a work of art and part of the Blanton’s permanent collection.

Over the past several decades, museum architecture discourse has been embroiled in an argument as to whether a building should be a white box framing and playing a supporting role to a collection, or whether it should assert its own personality. In an attempt to attract visitors, many museum buildings have become singular points of attraction and branding, rivaling the collections they contain.

Texas has examples of important museum collections that exist within extraordinary buildings. Both the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth by Louis Kahn and The Menil Collection in Houston by Renzo Piano hold an important place as part of the architectural discourse of the late 20th century. They are buildings whose prominence in an architectural context rivals that of the collections they hold — but, for all their importance, these buildings remain separate from the collections and would never be confused with them.

The disciplines of the contemporary art world and that of architecture are largely separate, with few examples of successful crossover; we live in an era in which the technical demands and cultural complexity of the disciplines have led to specialization and separation. Presenting works of architecture as an integral part of a museum or gallery collection is not common practice. Each year, a different architect is invited to design a temporary Serpentine Pavilion in London. The pavilions themselves are what people come to see, but they are nevertheless understood largely within the context of architecture and design and not as contemporary art.

Closer in typology to the Kelly building is Olafur Eliasson’s “Your Rainbow Panorama,” a colorful permanent circular pavilion built on the rooftop of the ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum in Denmark. It has both an exterior and interior identity and the ambiguous program of contemplative experience. While the Eliasson project is a logical extension of his immersive gallery and museum interior installation work, the Kelly building at first might not seem to be clearly related to the artist’s body of work. However, as the Blanton’s supporting show demonstrates, there turn out to be many formal connections to his oeuvre: This first and only building design is an anomaly, and there is a reason for this.

The Kelly building — recently named “Austin” — was not originally intended for a museum or gallery context. It was designed in 1987 as a chapel for a site in California — the private estate of the TV producer Douglas Cramer. Cramer, a collector of contemporary art, was a friend of Kelly’s and had acquired many of his works.

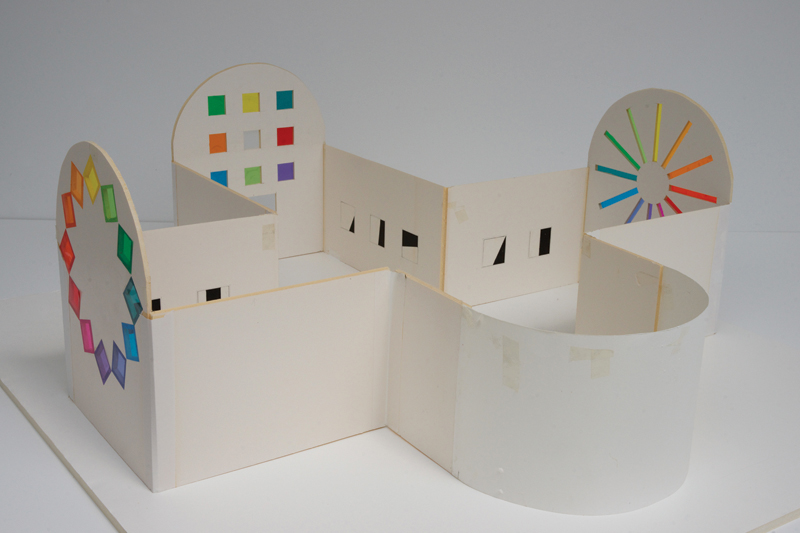

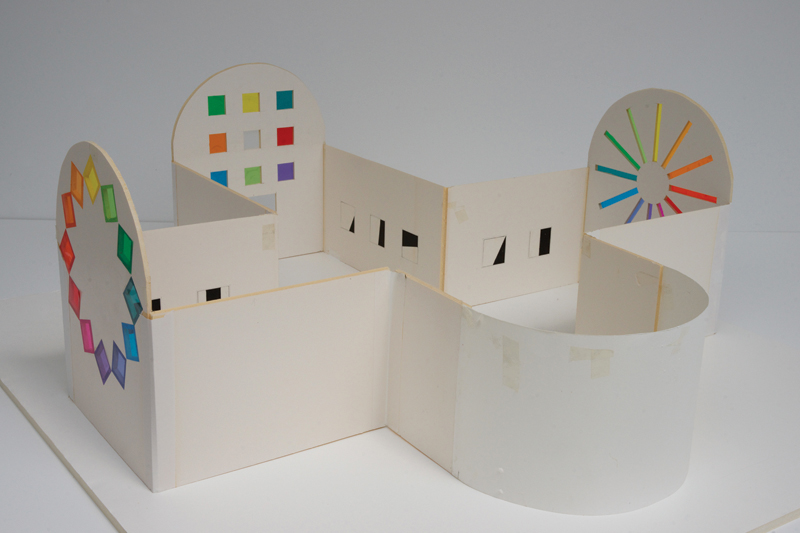

The foam core model above was made by Kelly in the 1980s. It sat idle in his upstate New York studio, along with sketches of the “Stations of the Cross” and the stained glass window wall elevations, for some 25 years before the Blanton took the project on.

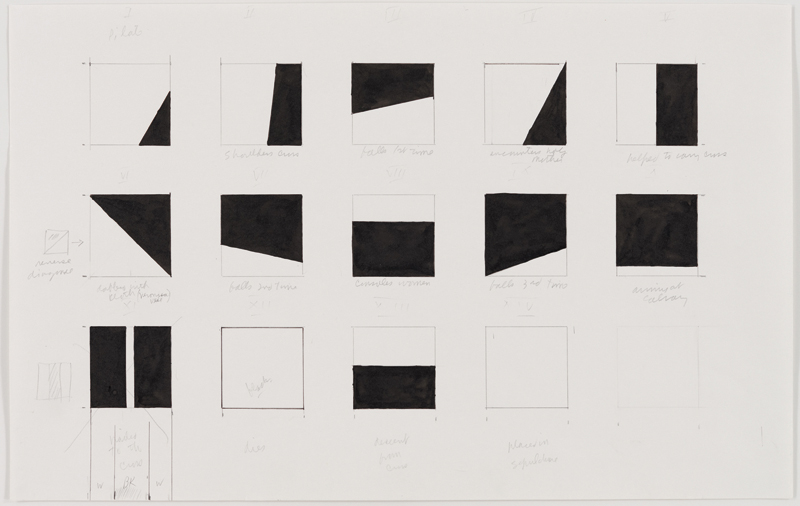

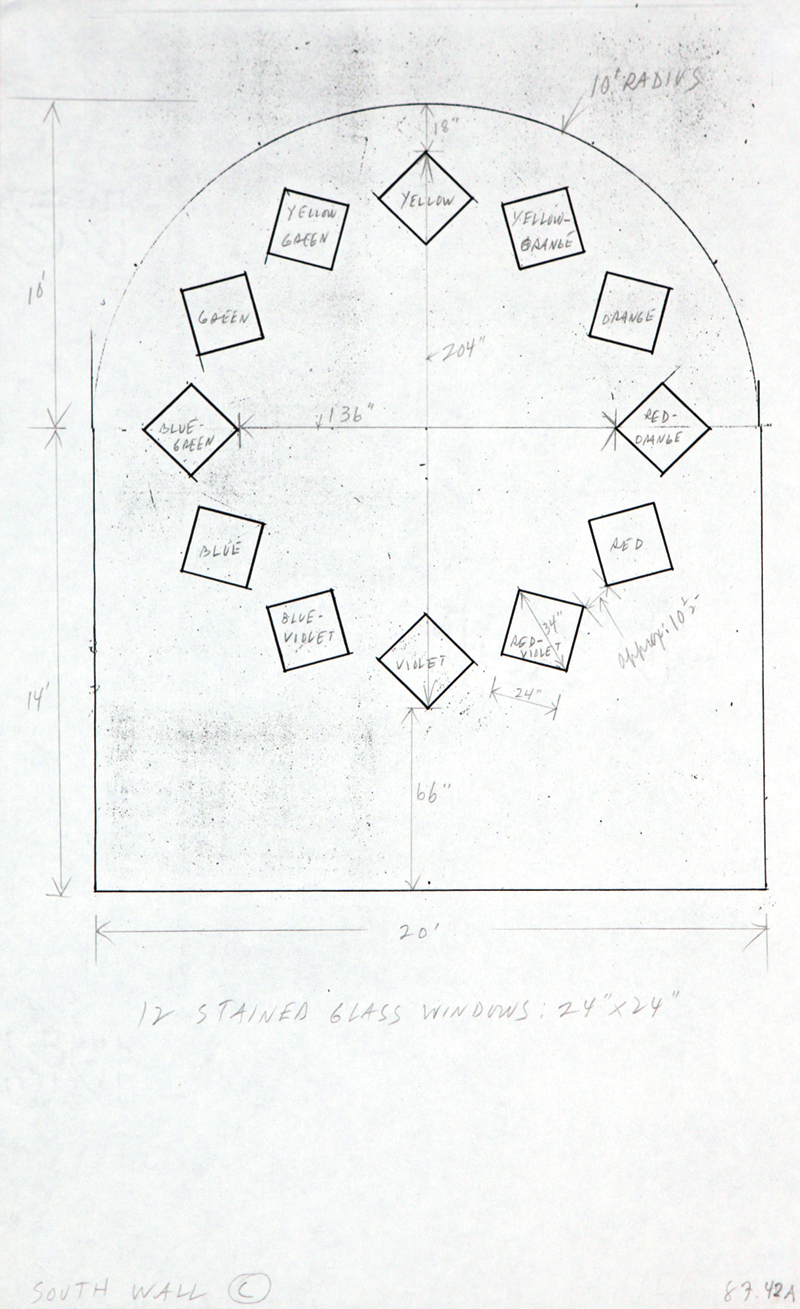

Kelly selected a distillation of elements from early Romanesque and Cistercian architecture, about which — though he subscribed to no Christian faith — he had gained deep knowledge from his years studying churches in France: an exterior narthex, Roman cross plan, nave, east and west transept complete with stained glass windows, and an apse. The building design eventually came to include abstract depictions of the Stations of the Cross hung along the nave and transept walls, as well as a totemic crucifix (just its vertical member) positioned where a chapel would have an altar.

Although he’d never done anything like this before, Kelly’s moves make sense for a couple of reasons. First, he was commissioned specifically to design a chapel, so drawing on historical forms of Christian architecture, which he’d studied, is a logical thing to do. Second, although this technique of collaging simplified forms of historical architecture is not immediately apparent in Kelly’s body of artwork, it was a common design tool for architects during the postmodern period of the mid-80s, when the building was conceived.

Although it was his only building design, Kelly’s body of work does contain many fascinating examples where he has employed architectural techniques and transferred formal elements from the world of architecture to represent them in his art. One example would be “Study for Window” (1949), where he painted an elevation drawing of a window he saw in the Museum of Modern Art in Paris using a technique of transference called orthographic projection — which is a form of transference and one of what Yve-Alain Bois, the author of the Kelly Catalogue Raissoné, calls the artist’s “non-compositional strategies.”

By using orthographic projection, Kelly was able to avoid having to “interpret” the window and represent what he saw in a conventional pictorial way. Instead he is simply projecting it from the world straight to the canvas in the same way an architect uses orthographic projection to accurately represent a window’s proportions and dimensions. In a sense, it’s not a “picture” of the window, but closer to the window itself — in the way a shadow is related to its object. A shadow does not interpret an object; rather, it forms through a mechanical process. The painting is abstracted to the point where its origin is no longer legible. Kelly takes this shadow logic a step further and gives the projection a life of its own in the painting, detached from its original object.

Kelly’s artwork, which often draws on things he sees in the world, is abstracted to the point where the original vision is rarely recognizable. Neither the Stations of the Cross nor the crucifix (totem) within the Kelly building are at once recognizable as in any way related to their traditional counterparts in history. This invites interpretation.

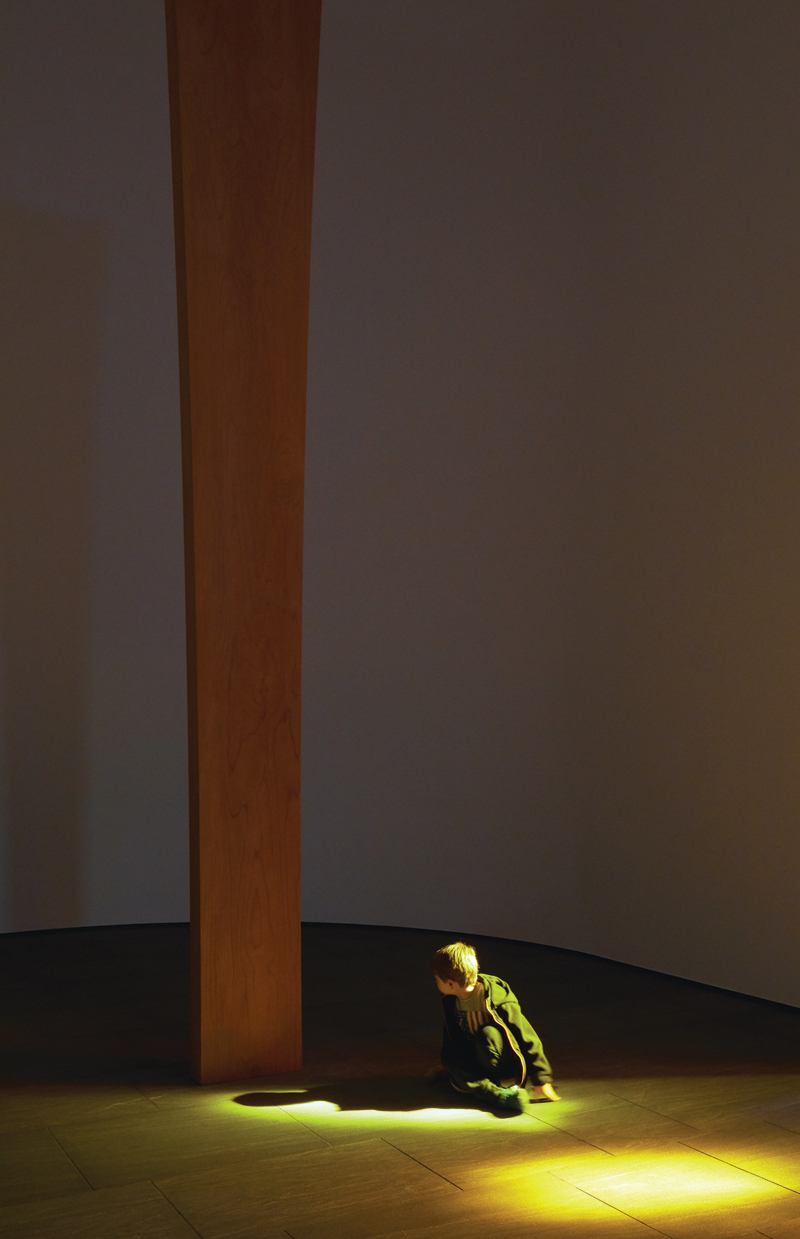

The placement of the redwood “totem” corresponds to that of an altar in a Christian church. Kelly himself, however, was not religious, and did not conceive of the project as a place of worship. Photo by Leonid Furmansky.

The building itself, however, with all of its forms derived from Christian architecture, clearly reads as a chapel. There are moments of abstraction from certain points of view, but, taken as a whole, it looks like a chapel.

During the 1980s, Kelly worked with an architect in Santa Barbara, California, to produce blueprints of the Cramer chapel. He also started a conversation with fabricators about the sculptures that would adorn the interior (the same fabricators were hired for Austin). And he produced a crude foam-core model, which lived in his upstate New York studio for the next 25 years. But the chapel was never realized.

In 2012, Hiram Butler, a UT alumnus, art historian, collector, and art dealer, became aware of the unbuilt chapel through a chance encounter with Kelly, and offered to try to find it a home in Texas. Butler has a passion for artist-designed building projects, having spearheaded the construction of several, including the Live Oak Friends Meeting House in Houston, which wraps around a Turrell Skyspace at

its center. Butler’s idea for the Meeting House came as a reaction to the negativity he saw coming out of the culture wars — in particular, the attacks on the LGBT community in the early 1990s. He wanted to create a contemplative space open to all people as a counterpoint to the divisiveness he saw in the political landscape.

Butler saw in the Kelly chapel a similar programmatic idea to the Quaker Meeting House — an artist-designed contemplative space open to all. He assembled the team of Overland Partners and Linbeck Group to build the Kelly project. The three had completed the construction of many of Turrell’s Skyspaces, including one at UT Austin.

Butler reached out to several institutions to gauge interest in the Kelly chapel. The Blanton finally took it on in 2013. Director Simone Wicha assumed the difficult work of fundraising and shepherding the $23 million project to realization, an impressive achievement.

For the Blanton, this project is a bold curatorial move: to take the collection outside the confines of its conservative buildings and to present an untested building idea as part of the museum’s collection. After all, among Kelly’s significant achievements, there are no architectural examples one can point at to predict success.

Sited on axis with the wedge-shaped space between the two Blanton buildings, Austin aligns with the eastern museum face. The space between the two existing Blanton museum buildings, which were designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Wood, is a tree-shaded courtyard. The rationale for the wedge-shaped courtyard was that one face of the wedge aligns with the Austin city grid and the other the University of Texas grid.

This assignment of meaning to the grids is difficult to read in the Blanton building pair. The space between the buildings reads as a wedge, but the grid alignments are not legible. The Kelly building is situated at the narrow end of the wedge, so the Blanton buildings create a tapering frame at the top of which is the Kelly building. The wedge-shaped courtyard points to it.

The Kelly building’s cruciform plan and extruded, toy-like form make the skew off the city grid clear. Its obvious partner at the wide end of the wedge is the Texas State Capitol, from which it appears to be turning away. The building’s rotation becomes apparent as one searches for an alignment. The most obvious object in the field is the State Capitol, to which it appears unmistakably misaligned.

What’s apparent from the building exterior is that it employs a formal restraint and scale manipulation familiar from Kelly’s artwork, much of which is subtly three-dimensional. Small increments of space and adjustments are made to the work so that it engages the space it occupies as a whole, often giving it the illusion of buoyancy and spatial depth in what appears at first to be a spatially unassuming graphic artwork. As is the case with architecture, these subtle effects can be perceived only when you’re in front of the actual work and are lost in any representation of it.

For instance, in Kelly’s “Dark Blue Panel” (1985 — about the time Kelly would have been designing the building), a large, roughly 8-ft-by-9-ft almost square dark blue canvas has been manipulated at its edges. The blue evokes a deep night sky, and appears flat, at first. However, the edges of the canvas are slightly concave, and this curved inflection toward the center of the canvas, together with its deep blue hue, call to mind the curvature of the earth and the dome of the sky. The slightly bowed edges activate the canvas spatially from the margins. In the painting, the initial experience is of a field of color, but on more careful examination one becomes aware of a deeper vaulted space employed by the curved edges of the field. The effect is breathtaking, and gives a feeling of space itself, as if one were peering up into a vault.

An interesting parallel between the building and this painting is the repetition of the four vaults in the four cardinal directions as the building’s spatial frame and the four shallow vaults that make the frame of the painting and activate its illusion of space. Approaching the Kelly building from any direction involves a similar shift in scale.

Overland Partners has done a masterful job of detailing the building — of taking Kelly’s conceptual design and working through the challenging job of materializing it. With many cues to the chapel’s identity as a building concealed, such as flashing, vents, and roofing, the structure takes on a scaleless quality from certain points of view, especially seen from the sides or rear, where it resembles an uninterrupted stone surface. As water sheets over the surface, it flows down to concealed gutters at grade, hinting at a secret subterranean life — a very well-concealed basement where all the mechanical equipment lives.

One recent rainy day, the stone roof and walls, which flow seamlessly together, were streaked in rainwater. This interaction with the elements, common to architecture, is rarely seen in any Kelly artwork, hinting at the possibility of the building weathering over time.

On the interior, the colored glass windows have a popular graphic quality whose intensity relies on the abundance of white space provided by the vaults. On an overcast day, the glow from the windows creates a nuanced projection of color onto the surrounding surfaces, which, like the wall weathering on the exterior, varies over time. The artificial lighting (required by code in a public building) is in competition with the subtler effects of the changing natural light but can be controlled. When the lights were turned off, the result was a gradation from the bright candy-colored windows to a darker, obscure condition at the crossing.

Daylight entering the building through the stained glass windows at times washes the walls in subtle gradients of color, and at others fires beams of a particular hue. Photo by Leonid Furmansky.

There’s an emptiness and darkness to the interior space at its intersection that serves as a necessary counterpoint to the bright graphics of the glass windows: The color does not penetrate to where the apse and totem are located. This north end of the building is therefore a dark anchor point.

The apse, which frames the totem, is a half dome vault without natural light. The interior form of this vault, with its concave white boundless surface, delivers an effect similar to the scalelessness of the exterior. The lack of light makes its partial dome form difficult to read in the dim light, giving it a formlessness and obscurity, a necessary counterpoint to the cheery Instagram-ready windows in the transept and nave.

Comparisons have been drawn to the Rothko Chapel in Houston and the Chapelle du Rosaire, in Vence; however, both these buildings are largely interior spaces conceived by the artist and housed in unremarkable buildings. The Kelly building is a more ambitious type. The artist envisioned it as a whole, with a very specific exterior and interior identity that has changed very little since its inception in the 1980s. This is what makes the addition of Kelly’s building to the University of Texas interesting.

Here, on public university grounds, presenting something unexpected in a museum collection — a building, as a work of art — might get the attention of people who would not typically visit the museum. By crossing over to the messy realm of architecture, with its day-to-day interactions with the world, Austin could act as an accidental point of entry to the realm of contemporary art and become meaningful to people who might have never heard of Ellsworth Kelly, nor explored the Blanton.

Murray Legge, FAIA, is principal of Murray Legge Architecture in Austin and a co-founder of Legge Lewis Legge.