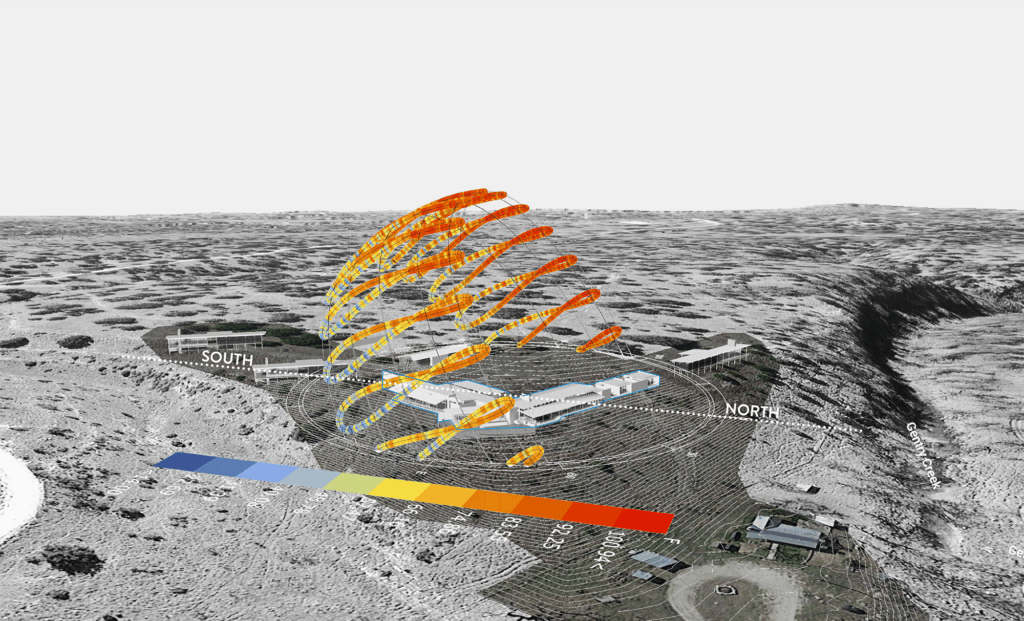

Design for a Changing Climate

Concrete Architecture

Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024

When writers Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin of Los Angeles write a book, they use what architects love: a blueprint. Their books of beloved and rarely seen buildings include crisp and tight sentences and ruminative essays about whatever the subject may be.

The Atlas of Never Built Architecture (Phaidon, 2024), reviewed in the spring issue of this magazine, followed that blueprint. Concrete Architecture (Phaidon, 2024), a 352-page tourist guide highlighting 300 buildings designed during the 20th and 21st centuries, does too.

One of the delights of their books is the meticulous research and their commitment to highlighting a variety of projects. They like the practical, small, and peculiar as much as they do the ostentatious.

In Concrete Architecture, Lubell and Goldin include a demolished parking garage in London. The prefabricated Welbeck Street car park was designed by Michael Blampied and Partners and built in 1970 for the Debenhams department store. Garages are practical. But this one had a diamond-patterned facade wrapped around a central elevator and staircase. It was torn down in 2019 after failing to achieve historic protections.

Tvísöngur, meaning “the duet,” is a sound sculpture by the German artist Lukas Kühne near Seyðisfjörður, Iceland. It’s one of those projects that makes you want to book a pricey flight just to see. Its interconnected igloo shapes of varying sizes make it look like an abandoned, experimental spaceship. But in reality, it’s a prideful representation of Icelandic music, and what the authors call “singing concrete.”

Some featured projects are eccentric monuments from the Soviet era, including Igor A. Vasilevsky’s Druzhba Sanatorium in Kurpaty, Ukraine, built in 1985. Get this: The Soviet government mandated rest for workers, including two weeks of paid vacation time each year. Sanatoriums were a go-to place to relax, get a massage, and—per the name Druzhba, which means “friendship”—make community. It’s an ambitious, towering space station-like structure in harmony (even with all that concrete!) with nature. It’s what college residence halls should be.

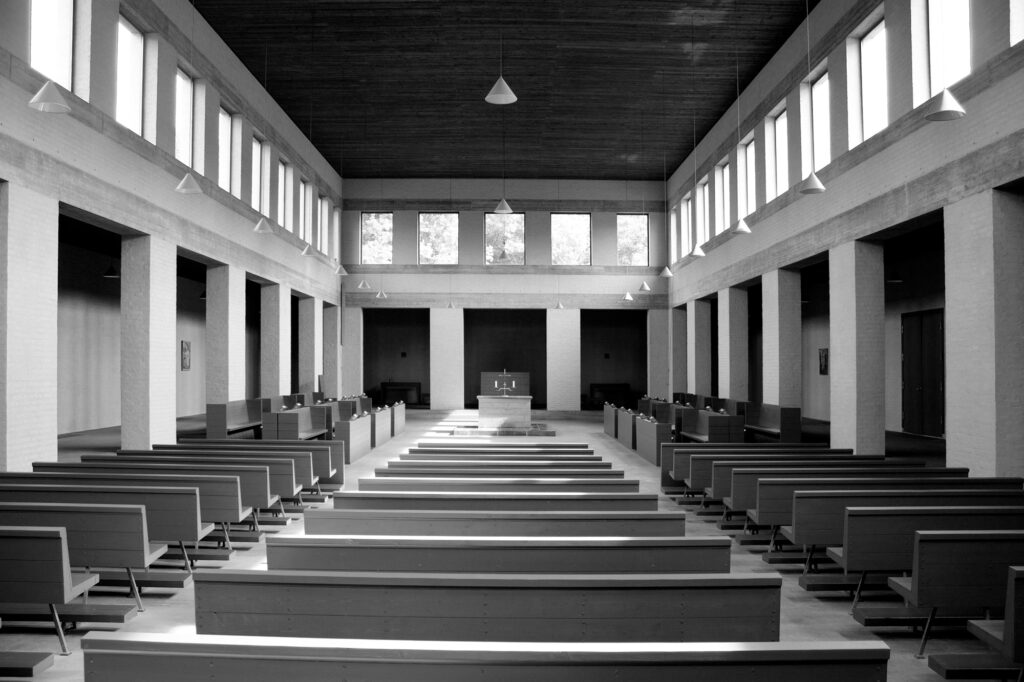

When it comes to Texas sites, there’s no doubt which you would expect to see. And, duh, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth makes an appearance. The engineering and concrete feat by Louis Kahn, which opened in 1972, was in part saved by his sparring partner, August Komendant, an Estonian engineer who worked with Kahn on many projects. (One joke is that commissions were taken between their fights.) There are many rewards on the campus, including the calming landscape designed by Harriet Pattison, and, of course, the art collection. But it’s the museum’s undulating barreled vaults, modeled on since-demolished grain silos, that stand as the project’s true architectural triumph and as a model for other buildings in the city.

The Kimbell’s neighbor, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth by Tadao Ando, is also featured. When the building opened in 2002, the oldest art museum in the state finally got a megachurch for its contemporary and modern art collection. The complex of five rectangular glass pavilions supported by Y-shaped columns centers around a calming pond. It is a signature Ando design, the authors argue, because it reflects his trademark minimalism and mix of light and solitude, even when the exhibitions are loud.

And those small projects? They’re represented by the Webb Chapel Park Pavilion in Dallas. Built in 2012 by Studio Joseph, it was constructed as part of the city’s plans to replace outdated shaded areas in the city’s parks. The street view and photo don’t do it justice. From a distance, it appears as a minimalist facility in the middle of the northwest Dallas park. But get closer, and you see it’s far more complex—and a delight to sit under. The structure is held up by only three supports, and inside are four pyramidal chimneys of varying sizes painted in a lush, vibrant yellow. The reveal is a surprise and a welcome shelter from the state’s erratic weather.

If one includes the Kimbell as an example of architecture in the state, then one must also include at least one project by Lake Flato, right? Lubell and Goldin highlight the firm’s pavilion for San Antonio’s Confluence Park, built around the theme of connecting the built and natural environments. Central to the design are 22 sculptural concrete petals that emerge from the ground to form a canopy. The petals, though, look weightless and also allow rainwater to flow down into the grass below and be stored for later.

Concrete, as proven in this book, isn’t just another material but one that also inspires, engages, and allows for a sense of peace, or at least a reprieve from the challenges and banality of life.

James Russell is a journalist in Fort Worth writing about art, the built environment, and politics. His writing has appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine, CityLab, Arts and Culture Texas, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, among others.

Design for a Changing Climate

Reimagining the Courtyard House

Shaping the Culinary Experience

Modern Hospitality Meets Cultural Legacy

At the Intersection of Neuroscience and Design

Snøhetta Transposes the Borderland

Designing for Neurodiverse Students

These finishes and furnishings focus on the power of color to influence mood, productivity, and overall well-being.

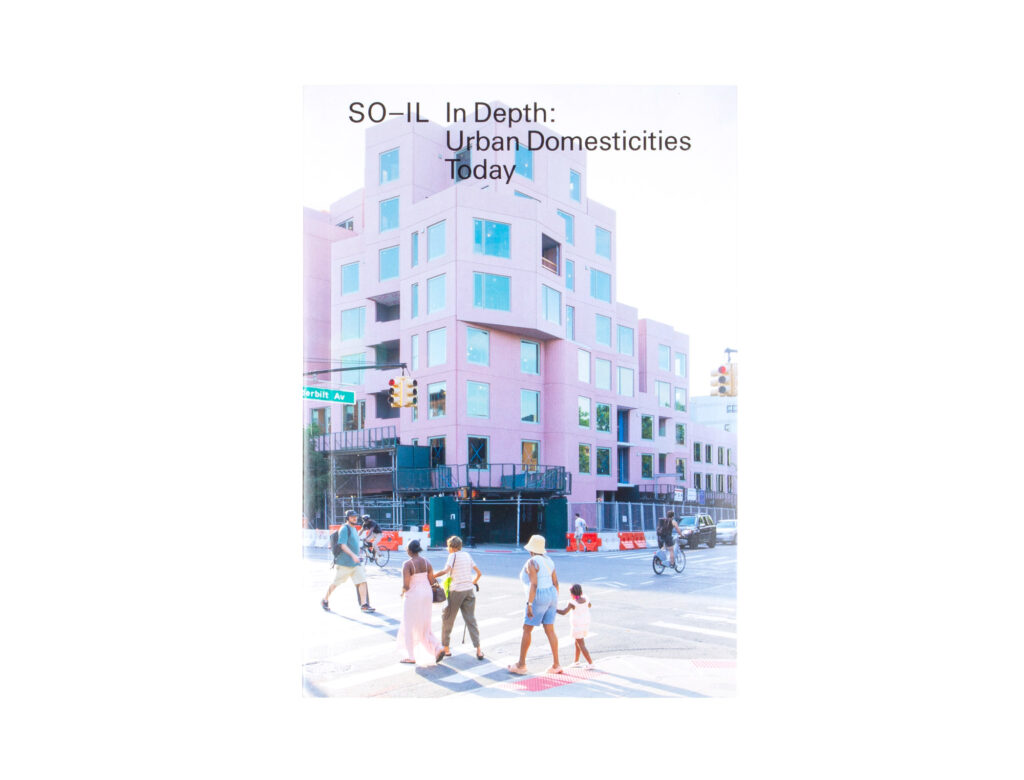

In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today

Edited by Florian Idenburg, Jing Liu, et al.

Lars Müller, 2025