Design for a Changing Climate

Snøhetta Transposes the Borderland

“Only a few, who remain children at heart, can ever find that fair, lost path again…. They, and only they, can bring us tidings from that dear country where we once sojourned and from which we must evermore be exiles. The world calls them its singers and poets and artists and story-tellers; but they are just people who have never forgotten the way to fairyland.” —L.M. Montgomery, The Story Girl

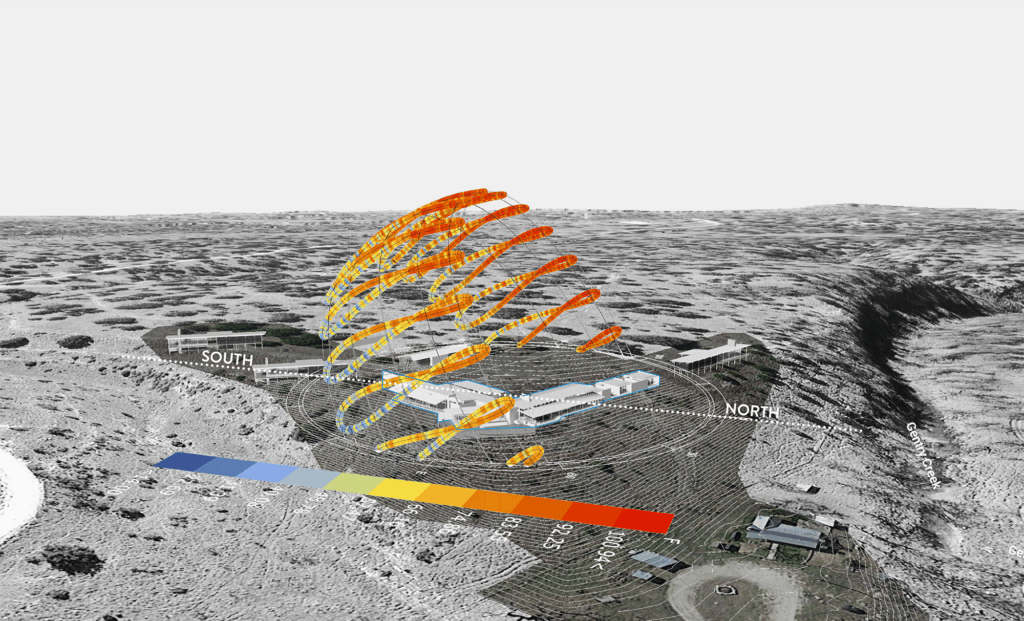

El Paso is five-eighths sky, underscored by mountains from nearly every view. On cloudless days—so most days—the entire sky stretches out in baby blue; on others, silky cirrus clouds hang like a mantilla high over the mountain range that spans El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. On a map, the El Paso end of the range points toward the downtown grid, where seven possible exits from I-10 take you into the city’s core. The last westbound exit, Santa Fe Street, carries you south toward the silhouette of La Nube—the city’s new STEAM discovery center, designed by Snøhetta. The top of the building’s 89 feet peeks from behind a row of red brick offices, a portmanteau of cloud and home, reminiscent of a drawing come to life, insistent on its belonging.

Snøhetta has a native connection to El Paso. One of the firm’s founding partners, Elaine Molinar, AIA, grew up here and ensured that La Nube would reflect the city’s inimitable nature—especially its vast, defining sky—while brightening El Paso’s historic downtown with the vernacular of childhood imagination.

As you approach the building, even the sidewalks seem to celebrate the sky, with blue glass aggregate framing the ground upon which La Nube seems to float. The site was offered to the design team in the way an empty appliance box is handed to a child—as an invitation to play, to imagine something new.

Housing a former bus maintenance facility at the intersection of two trash collection zones and sharing a wall with a submerged railway, 201 West Main Street embodied its gritty history. These less-than-ideal conditions confronted Snøhetta but perhaps gave them that much more creative freedom. La Nube’s playful form responds cheekily to its context, reframing it forever. You do not see the 60-foot piers driven deep into unforgiving soil; what you see is a 70,000-sf building hovering happily.

La Nube’s brawny 651 tons of steel are arranged to look weightless. An aluminum-tiled curtain wall—smooth to the touch and pixelated in shifting shades of zinc white and grey—curves around the compass points as if it’s always on the move. The steel and glass body seems almost sentient. The roof splits open knowingly to the east, the morning light swinging in, while to the west, an out-of-scale dormer window pops up from the roof like a giant periscope. Fenestration patterns climb and descend the facade, beginning or ending in arches that echo the geometry of two nearby buildings. The glazing itself is patterned with what looks like condensation—millions of raised ceramic droplets, each maybe a millimeter in size. They lend La Nube’s galleries their own sensation of cloud cover and, from the outside, create the impression that the entire building might just be a mischievous rendering.

La Nube’s design—thoughtful across all scales, abilities, and sensitivities—is evident not only in its architecture, both interior and exterior, but also in its graphic design, sill and header details, mounting heights, lighting, acoustics, and even its operations. La Nube offers sensory-friendly hours and caregiver passes, among other thoughtful rewrites of convention. As a project developed during the COVID era, La Nube was hit hard with the contingencies that stymied us all, but it seemed to taunt the pandemic. Its program is the antithesis of “no contact.” John Hand, project leader for Arup, La Nube’s structural engineer, shares that “the controlling design case for vibration in the multipurpose room was a Quinceanera.” For those unfamiliar with a “Quince,” as it is called in El Paso, it is a whirling, coming-of-age celebration with family and friends, friends’ families, and friends of their friends. It’s a perfectly logical design criterion for any assembly space in El Paso—the very opposite of lockdown.

Deft partnering and careful shepherding brought La Nube to life, allowing its original ideas to remain unadulterated and fully realized. What began as a city bond project for a children’s museum developed into La Nube through a generous infusion of private equity, community investment, and a shared sense of protectiveness on the part of all parties.

The El Paso Community Foundation—which has made an art of civic project delivery—took the lead, helping the project avoid the hopper that can often derail iconic public works. Eric Pearson, the foundation’s president and CEO, explained, “The foundation and its board envisioned a place that not only educates people within its walls but inspires them”—something, he notes, that can only happen through encounter.

This is why, before the foundation hired renowned educator, writer, critic, and consultant Reed Kroloff, AIA, to lead the competition that ultimately selected Snøhetta, they first engaged Gyroscope, a multidisciplinary design studio known for STEAM exhibits and museum master planning.

The vision for meaningful encounters is emphatic from the moment of entry, where visitors are greeted by an expansive concave touch screen—Gyroscope’s Connected Sky exhibit. Setting the tone for La Nube’s boundaryless experience, this first “engagement”—a term Harry Mark, FAIA, a principal with RSM Design, uses when speaking about La Nube’s exhibits—is a virtual yet tangible connection to a fiber-coupled screen at La Rodadora Espacio Interactivo, the children’s museum in Ciudad Juárez. Here, real people from one city appear on the sister screen in the other to play games in real time, their respective screens pulsing between silhouette and full image, mapping their contact—technology creating art.

Gyroscope’s synesthetic work at La Nube beckons young hands to the messages at each stop. These stops are not lessons; they are invitations to see something new—or differently. Snøhetta’s architecture responds with what Elaine Molinar describes as “broad views and key moments, long vistas”—a studied interplay of foreground and background. RSM Design expanded this dialogue through environmental graphics, poring over details with Snøhetta and Gyroscope and organizing tomes of information to be embedded into La Nube’s architecture. For the signage, the RSM team played with dichroic materials, exploring light transmission and reflection, and rediscovered how children engage with letterforms. The result is a building—and a site—alive with all the ways information can reach us and open new perspectives.

This spirit of integration is especially evident in the massive, Gyroscope-designed, 50-foot-tall climbing structure that spans the atrium, intertwined with the work of Snøhetta and Arup. Arup uses the voluminous structure to brace the facade against wind loads, while Snøhetta wraps it in a series of long-span, helically curved stairs. Arup engineered the stairs using custom steel box girders with 2-inch-thick flanges. Signs of interdependence are everywhere—creating what would otherwise be impossible.

At the top of the climber, the Flow exhibit suspends thousands of gallons of water nearly 60 feet above ground. Here, a refreshing humidity fills the air, along with a faint scent of swimming pools and the sound of moving water. Across the same floor, a giant sun-shaped marimba resonates with deep, wooden tones triggered by those who stop to play underneath it. Somewhat centered along the north wall is the cathedral-scale arched entrance to Fab Lab El Paso—La Nube’s makerspace and home to a rich and evolving program of its own. All this precipitates beneath the exposed vaults of Snøhetta’s arches, where a math mural climbs the back wall, marking the vaults’ geometries.

Maintaining this cohesion throughout the construction also required the painstaking technical care and diplomacy of Exigo Architecture, the local architect of record. Paulina Lagos, AIA, who served as Exigo’s project architect, recalled the close collaboration between the design and construction teams that allowed for the realization of La Nube’s refined architectural effects. She cited the example of the 1,200 twinkling fiber-optic lights that push through the aluminum tiles of the facade: “They were meaningful because they were difficult”—all of it worth the effort to achieve what she calls the “quiet precision of La Nube’s detailing and assembly.”

Snøhetta’s competition proposal foretold a weaving together of ideas and people. It presented an exuberant collage of poppies; appropriated storybook drawings of clouds and children; Bernard the Bull and Max from Where the Wild Things Are; vignettes of El Paso history; hummingbirds and morning glories. The periwinkle, iris, violet, and plums of El Paso’s skies blended with the sage greens and blues of its botanical palette, washing over pages animated with scenes from the project’s narrative—including an aquamarine Buick GNX (Grand National Experimental) circling the site, seeming to signal how rooted, rare, and iconic this project would be. The proposal was, itself, a wild rumpus. It did include a building design, but the architectural concept that became La Nube was developed after the project began—an approach fully intended by Snøhetta. “We like it when a client chooses a team rather than a design,” said Molinar, emphasizing the kismet that comes of their process, one that pulls the fantastical from the existing.

It was important to Molinar, who helped guide the public art selection, that the animals on artist Christin Apodaca’s third-floor mural were drawn realistically, not as cartoons. Titled In Our Desert, There Is Magic, the piece honors the brilliance in nature’s original information. Snøhetta traffics in this form of revelation. Their calling card is not a style sent directly to construction documents; it is a working method, a way of being, that connects them deeply to each project. They call it transpositioning, a concept explored in their monograph Collective Intuition.

Transpositioning is Snøhetta’s badass riff on interdisciplinary practice and what brings their projects to life. A Snøhetta project team may include liberal arts graduates prototyping in the model shop, or landscape architects ideating on interior spaces. The method prioritizes intellectual craft—the often-missing link in what we build. It is the “A” in STEAM.

There is tremendous power in engaging our minds artfully with the facts, and La Nube offers El Paso extraordinary potential for powerful invention. It is more than a children’s museum by a renowned firm—it is a structure built in the dialect of imagination created for members of a generation who must become better and smarter than we were. They are the ones who will need to find a way forward out of the trouble we’ve handed down, and this is exactly the kind of place where that discovery might begin. The hunger for such a realm is evident in the numbers: At the time of publishing, more than 270,000 visitors have poured in since opening day—nearly matching the combined attendance of the city’s nearby museums and theater.

La Nube was conceived around the concept of the sky as a symbol of limitlessness, freedom, and inclusion. Like the sky, it belongs to and connects everyone, especially young people. The design brief reflected a deep commitment to equity and empathetic space that goes far beyond any policy. La Nube’s consideration for all ages, sizes, and abilities is essential to its magic. You can take a wheelchair into the climber—whether you need it or not. The grand staircases features additional handrails for children. English and Spanish are used interchangeably throughout, reflecting the way people often speak in the region. Hierarchies, as we know them, are reimagined and transformed.

I saw a woman pause in front of the restroom door, looking for the label “Women.” Instead, the sign read “Niñas.” She wasn’t disoriented—she was reoriented, awakened by mindful design to the invention and clarity behind the creation of La Nube.

Laura Foster has been a public sector architect for 15 years and currently practices in El Paso, where she lives in and is restoring the historic midcentury Hilles House.

Design for a Changing Climate

Reimagining the Courtyard House

Shaping the Culinary Experience

Modern Hospitality Meets Cultural Legacy

At the Intersection of Neuroscience and Design

Designing for Neurodiverse Students

These finishes and furnishings focus on the power of color to influence mood, productivity, and overall well-being.

In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today

Edited by Florian Idenburg, Jing Liu, et al.

Lars Müller, 2025

Concrete Architecture

Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024