Design for a Changing Climate

At the Intersection of Neuroscience and Design

For centuries, architects have pursued beauty and harmony by organizing form according to systems of proportion. Architectural forms, from the symmetry of Greek temples to the modular grids of modernist icons, exemplify the logic of proportion. Among these systems, the golden section, derived from the Fibonacci sequence, is the most renowned. Its influence peaked in the mid-20th century when Le Corbusier introduced Le Modulor, a human-scaled proportional system based on the golden section. It begins with the height of a man with his arms raised and uses the golden ratio to derive harmonious measurements.

Ironically, at the golden section’s peak of popularity, a crisis of confidence in proportion was taking shape. In 1951, the IX Triennale in Milan hosted a symposium titled “De Divina Proportione” that marked a turning point: Excitement over proportional systems gave way to skepticism about their relevance in a rapidly industrializing world. Rudolf Wittkower, one of the leading architectural historians of the time, observed that this was the first time in history that the foundational role of proportion in architecture was being seriously questioned.

A few years later, doubts erupted into public debate. At the 1957 Royal Institute of British Architects conference in London, attendees voted on the motion “Systems of proportion make good design easier and bad design more difficult.” It was soundly rejected—48 in favor and 60 against.

Reflecting on this shift, Wittkower warned that the belief in universal values, which form the philosophical core of proportional thinking, had been eroding for over two centuries: “It can surely not be won back by an act of majority decision.” Bruno Zevi, another major voice at the conference, was even more blunt: “No one really believes any longer in proportional systems.”

Despite decades of doubt and debate, the golden section still occupies architects’ minds whenever proportion is mentioned—yet it represents only one chapter in a much larger story.

Mathematically, the appeal of the golden section comes from the additive rule of the Fibonacci sequence, where each term equals the sum of the two before it. However, other sequences governed by similar additive rules also generate noteworthy proportions. For example, the silver ratio arises from the Pell sequence, and the plastic number underlies the proportional system developed by Dutch architect and Benedictine monk Dom Hans van der Laan. Despite their potential, both the silver ratio and the plastic number are seldom used in architectural design today. Here we turn our attention to the plastic number system because of its remarkable connection to human perception.

Van der Laan’s plastic number system took shape in the 1940s and 1950s and was introduced in his 1960 book Le Nombre Plastique. Rather than relying on abstract mathematical rules, his approach directly addresses how we distinguish size differences in three-dimensional space. The mathematical structure of this system was later formalized by Richard Padovan, and today it is known as the Padovan sequence (or Cordonnier sequence, after the French architect Gérard Cordonnier, who explored similar recursive patterns).

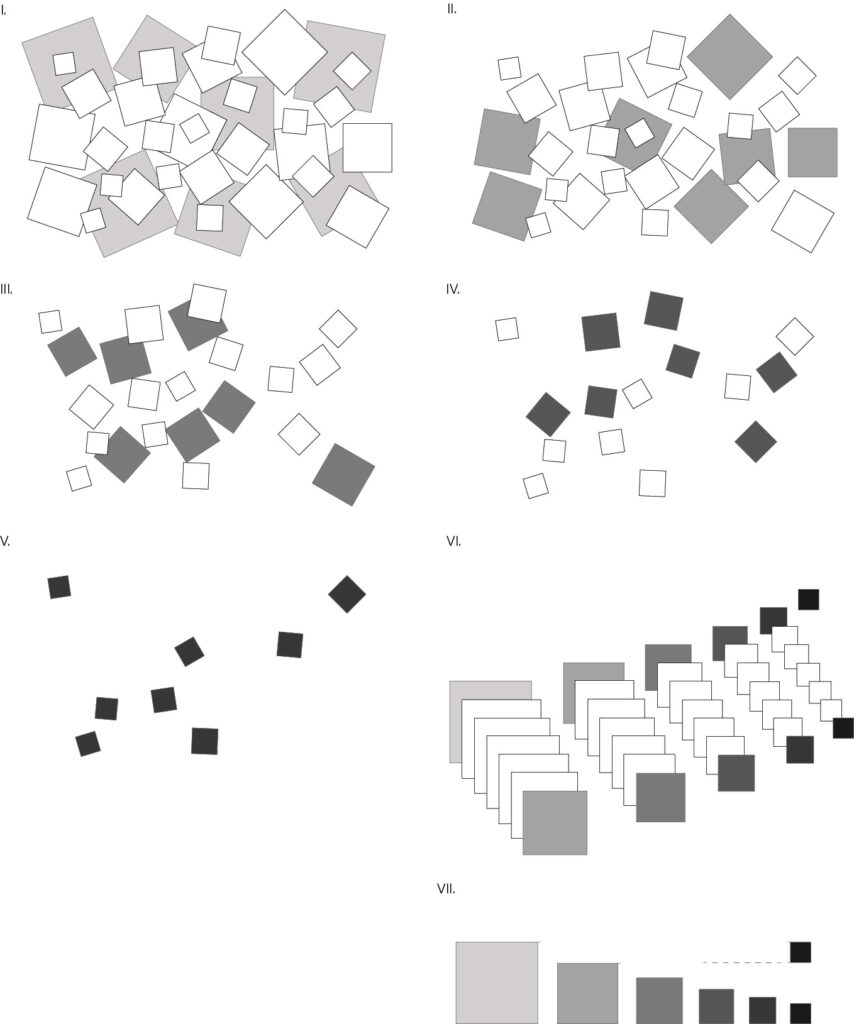

As a child, Van der Laan visited his father’s construction sites and became fascinated by the simple act of sifting gravel. He observed that large pebbles stayed on the sieve while smaller ones slipped through, and that none matched exactly the size of the sieve’s holes. He realized that natural forms rarely align with the precise measures devised by humans. To sort the gravel, workers used two sieves with slightly different hole sizes, capturing stones whose diameters lay between those limits. Later in life, Van der Laan coined the term “type of size” to describe groups of objects differing only by subtle, often imperceptible size differences. He then proposed a proportional method in which each size category accommodates variations so slight they go unnoticed. In other words, within the same “type of size,” object sizes differ by small, imperceptible amounts. And the measures that represent different types of size are separated by just-perceptible differences, a small difference that Van der Laan called the “margin of size.” These sizes, each separated by just-perceptible differences, form an ordered scale (“order of size”), in which every size relates to the next (Figure 1).

To test his idea of perceptible and imperceptible differences, Van der Laan conducted informal experiments with visitors at the St. Benedictusberg Abbey in Vaals, where he lived as a Benedictine monk. Using simple materials such as pebbles and cardboard squares, he asked visitors to group the items by similarity (Figure 2). He observed how small differences—too small to be noticed—did not affect the grouping, while differences that were just perceptible led visitors to form new groups. These insights into human perception became the foundation of the plastic number proportional system (Figure 3).

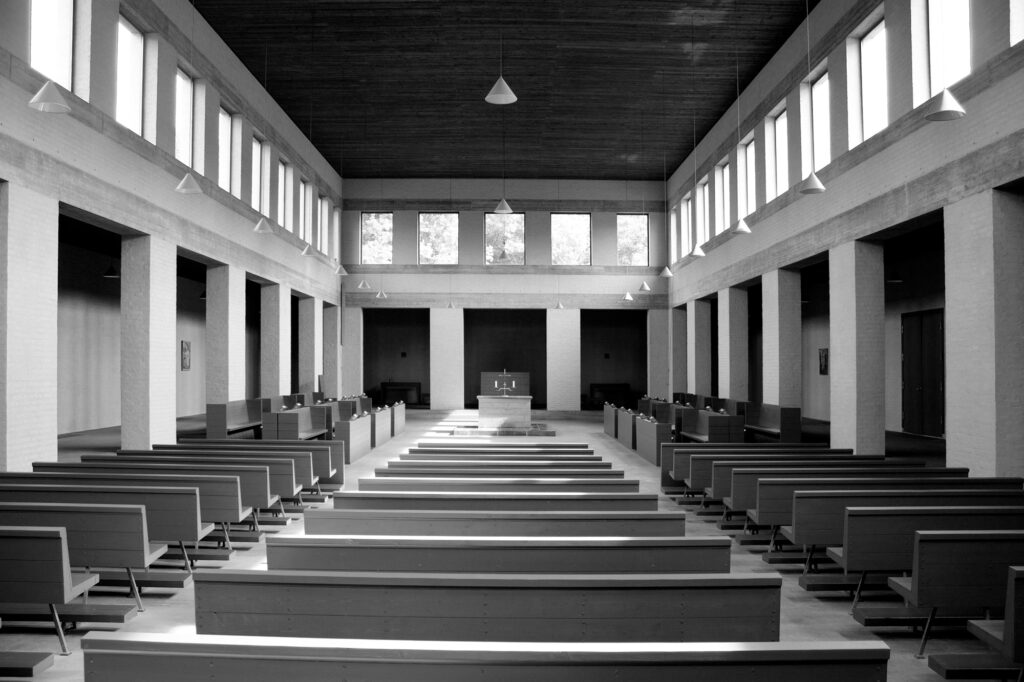

The St. Benedictusberg Abbey itself, which Van der Laan designed according to this system, remains the most comprehensive architectural expression of his proportional theory (Figures 4 and 5). The plastic number system is consistently expressed in three dimensions throughout the building. For example, in the liturgical hall shown in Figure 5, the spacing between columns creates rectangular openings with a 3:4 proportion, identified by Van der Laan as fundamental to the plastic number system. This ratio is maintained across both the upper and lower levels of the colonnade, varying only in scale. The result is a balanced composition that emphasizes clear perception of proportions, where repetition of a single proportion facilitates interaction with the interior space.

Although working in monastic isolation, Van der Laan developed ideas that parallel key principles of psychophysics—the scientific study of perceptual thresholds in size, brightness, and sound. Psychophysics had introduced the concept of the “just noticeable difference” (JND) in the 19th century, but this idea had little influence on architectural thought. Unaware of developments in the empirical science of perception, Van der Laan independently arrived at a similar notion and used minimal perceptible differences to define the intervals in his proportional system.

Designing with human perception in mind aims to make architecture not merely a physical shelter but a bridge between our minds and the built environment. By taking into account our perceptual and cognitive limitations, this approach helps designers to create environments that feel clear, coherent, and intuitively understandable.

Building on this approach and on modern scientific insights into perception, we are prepared to open a new chapter in the history of architectural proportion. We begin by asking how proportions are directly perceived in the built environment and how actual perceptual experience influences our behavior and experience.

To this end, we conduct experiments using methods of the scientific discipline called sensory psychophysics while trying to simulate conditions of natural behavior. These conditions reflect the basic fact that the built environment is made up of three-dimensional objects whose spatial properties people must be able to distinguish across various distances and angles of observation.

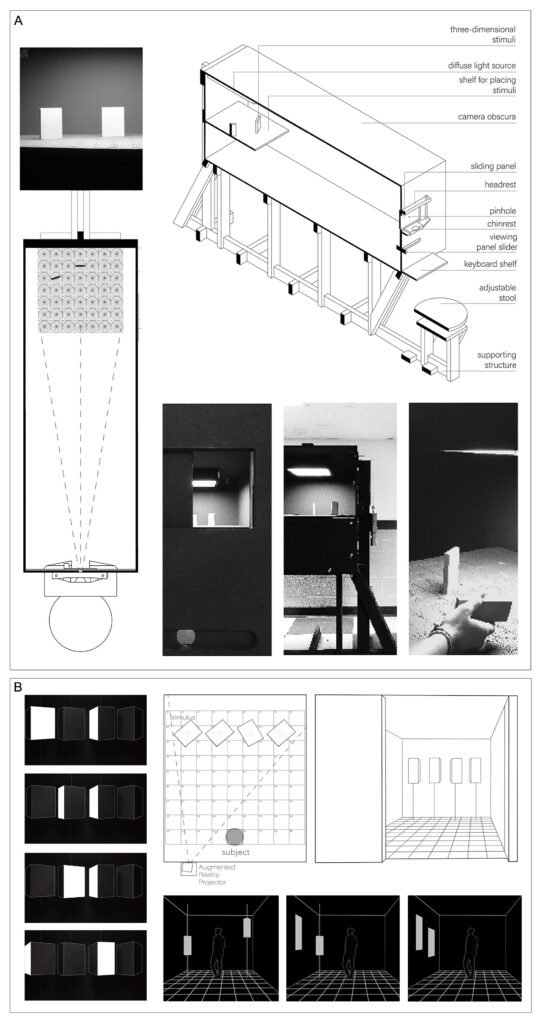

Our experiments have two formats: external observation and immersive observation. In external observation, participants view pairs of three‑dimensional objects presented inside an apparatus that resembles a camera obscura: a dark box with an illuminated shelf inside. On each trial, two objects are displayed on the shelf. Participants look into the box and compare objects’ proportions, making simple judgments such as “the front of the left object certainly has a larger proportion than the one on the right” (Figure 6A).

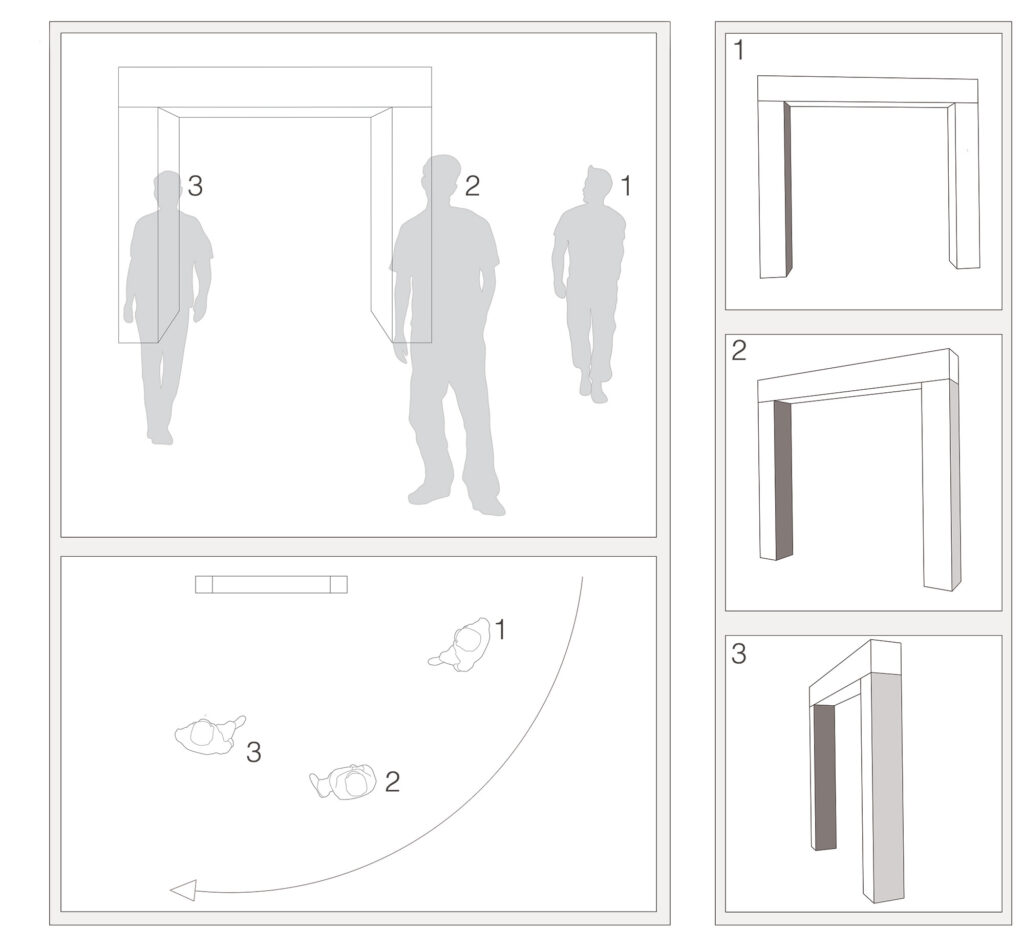

In immersive observation, people perform the same task while they stand or walk inside a darkened room, in which proportioned objects are mounted on adjustable vertical rods (Figure 6B). A scanning projector illuminates two faces of the objects at a time, and observers compare proportions of the illuminated faces while moving around, simulating the changing distances and perspective distortions experienced when walking through a real building.

We use proportions drawn from the plastic number system and set one “type of size” apart, so they should be just noticeably different. One of our first aims is to determine whether the just‑noticeable differences persist under realistic viewing conditions, as observers view objects at different angles. Indeed, we find that discrimination of three‑dimensional proportions varies significantly with object orientation and the perspective distortion introduced by user movement.

Our results challenge previous assumptions about proportion. They show, for example, that glorifying a single “perfect” proportion is misguided: not only because any given proportion stands among many that differ only slightly, but also because perspective distortion inevitably affects our perception. In light of this evidence, our understanding of the roles and effects of architectural proportion must fundamentally change.

First, proportion must be examined in three-dimensional space. Historically, architects relied on two‑dimensional drawings: plans, sections, and elevations that emphasize particular proportions. The golden section, especially, has been a recurring feature, identified in buildings from different eras, sparking debates over whether its recurring presence reflects genuine historical preference or the biases of later interpretation.

Our work renders the question of the golden section’s historical validity less relevant. As noted, the golden section originates in two‑dimensional media, not in the dynamic, three‑dimensional spaces we inhabit (Figure 7). Experience of proportion in the real world is shaped by movement, varying perspective, and the constantly changing bodily relationship to the environment. Understanding proportion therefore means reaching beyond ideal rectangles and fixed ratios to embrace the fluid nature of our spatial experience.

This brings us to the next point: Proportion is perceived dynamically. We must account for the movement and fluidity of our experience within built spaces to understand how proportion organizes our daily interactions. For example, does a certain ratio of architectural elements make us walk slower or faster? Does it guide us more intuitively toward an exit? Does it affect how readily we grasp the relationships between different rooms?

Imagine walking down the central nave of a famous church with which you have been familiar through many drawings and photographs. Instead of seeing column spacing on a flat plan, you experience it directly—dynamically and in vivid depth—as you move by them. When the columns stand close together, you quicken your pace because the altar feels farther away. When the gaps widen, you slow down as the altar seems closer.

Or imagine standing in a public plaza surrounded by benches, trees, and a central fountain. If the distances between these elements are tight, you may find the space crowded or overwhelming, prompting you to pass through quickly. But if the distances are generous and proportions well-balanced, the space feels open and inviting—encouraging you to pause and perhaps engage with others in a setting that naturally fosters social gathering.

Or consider walking down a wide urban street where the surrounding buildings are unusually not tall. The proportions feel off—the street is wide open while the buildings offer little vertical enclosure. You may feel exposed, as if you are crossing a vast, unprotected space rather than moving comfortably through it. Without the spatial “walls” that the appropriately proportioned buildings provide, the street lacks a sense of definition and shelter. You might feel a subtle sense of unease and avoid lingering. But when the height of the buildings is proportionate to the street’s width, the space feels enclosed yet open, encouraging a more relaxed pace and a sense of belonging within the urban fabric.

In effect, proportion becomes something we live, and not only see, when movement and bodily experience are taken into account. This basic insight transforms how we understand architecture itself.

Finally, the proportional ratios most relevant to our experience are not those celebrated for harmony, symbolism, or aesthetic appeal, but those that respect the limits of our perceptual systems. In other words, a proportion’s true significance lies not in abstract ideals but in its correspondence to the constraints of human perception, movement, and cognition.

This shift in perspective carries important implications for architectural practice and education. If proportion is not about adhering to a fixed series of revered ratios but about engaging directly with the reality of human perception, then designers must cultivate a new kind of sensitivity: one that attunes them to how subtle variations in size can guide movement, influence how we orient ourselves in space, and shape our overall experience of a place.

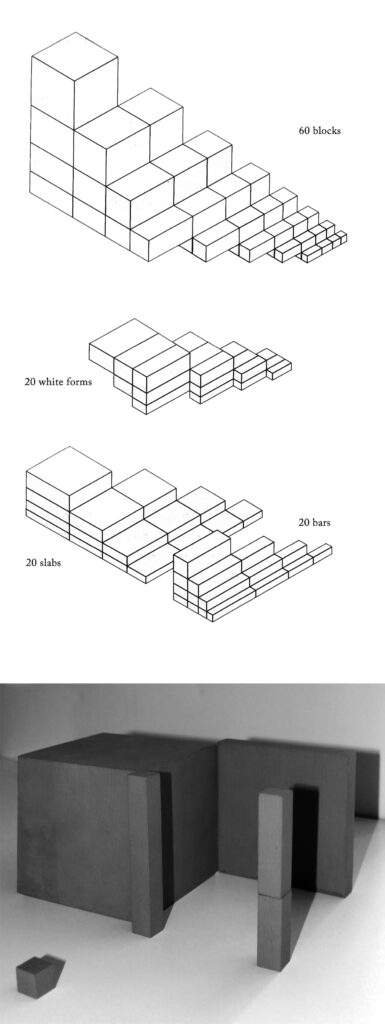

In architectural education, the new proportional thinking calls for a new kind of training that cultivates skills of perception instead of memorization of canonical rules. Drawing on our laboratory findings, we have created a program called “Vision Training for Designers.” As a point of departure, we use the plastic‑number tools devised by Van der Laan, most notably the Morphotheque, a set of 120 solid forms whose proportions follow the “authentic measures” of the plastic‑number system shown in Figure 3. The collection comprises 60 blocks, 20 slabs, 20 bars, and 20 intermediate “white forms,” as they were called by Van der Laan (Figure 8).

Through targeted exercises that engage both vision and touch, students first learn to sharpen their ability to detect, discriminate, and work with proportions in three spatial dimensions (Figure 9). This perceptual foundation enables future designers to use proportion deliberately as a tool to enhance spatial orientation, clarity, and coherence of built form. Through an understanding of how specific proportional relationships influence movement, perceived distance, and recognition of spatial hierarchies, proportion becomes an intentional instrument rather than a distant aesthetic ideal.

Tiziana Proietti is an architect and educator at the Christopher C. Gibbs College of Architecture, University of Oklahoma, where she studies perception of proportion using methods of sensory psychophysics and directs the Sense Base laboratory.

Sergei Gepshtein is a scientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, where he uses methods of neuroscience and psychophysics to study the perception of depth and motion, perceptual organization, planning of action, and dynamics of neural networks.

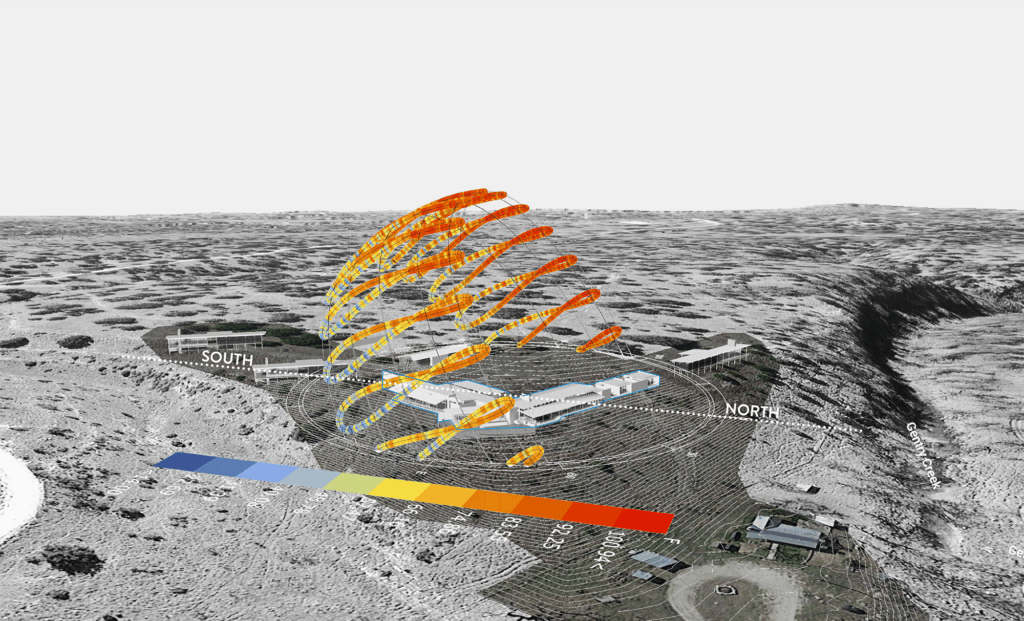

Design for a Changing Climate

Reimagining the Courtyard House

Shaping the Culinary Experience

Modern Hospitality Meets Cultural Legacy

Snøhetta Transposes the Borderland

Designing for Neurodiverse Students

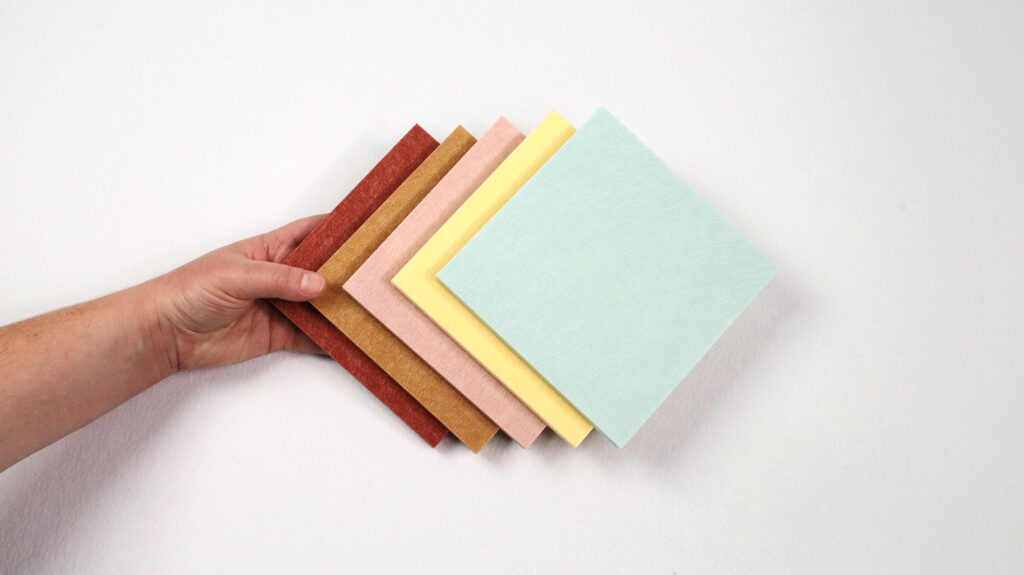

These finishes and furnishings focus on the power of color to influence mood, productivity, and overall well-being.

In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today

Edited by Florian Idenburg, Jing Liu, et al.

Lars Müller, 2025

Concrete Architecture

Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024

I found this article refreshing and engaging. So little theory makes it into the world of practice. This is not only thought-provoking, but its practical applications are clear. Linking the concept of proportion to human perception and dynamic perception, nonetheless, opens a phenomenological approach to proportion worthy of exploration. Thank you to the authors and to Texas Architect for including this article in this issue.

The Golden Ratio is not as foundational as you believe.

You just wrote 2,500 words on how to make proportions humanistic, and you did not once mention Vitruvian proportions.

The single most iconic non-religious image in Western Civilization is Leonardo da Vinci’s man with his arms out, in a circle – “Vitruvian Man.” It’s a study of how classical proportions reflect humanistic ideals that are pleasing without explanation. Vitruvius was the only Roman architect/engineer whose written work survived.

You do not have to design with explicit Roman columns to achieve this. Frank Lloyd Wright used classical, Vitruvian proportions in Fallingwater and many of his great works. He learned proportions from his mentor Louis Sullivan, who was classically trained. (You may try contest this, but Fallingwater features a central glass column. Measure that column, and the distance from its bottom to the lowest part of the building – pedestal, and the distance from the top to the uppermost part – entablature… a Roman-proportioned column).

Classical/Vitruvian proportions cannot be reduced to “the golden ratio” if you intend to implement them in practice, though the golden ratio can be found in some classical works. Architects who use these humanistic proportions in practice must know some basics about the Roman Orders – at minimum, pedestal, column, and entablature proportions.

I appreciate that you are thinking about the general subject. And I know that with just a couple exceptions, arch schools no longer require learning about or doing reps with classical proportions. But you should be much more aware of the thousands of years of practice and refinement of proportions in the Western world.

I apologize if my comments seem sharp. But you made a profound error of omission.

Texas: look at our traditional buildings. The pioneering Texas architects were literate. You don’t need to build old-fashioned buildings to tap into the humanistic genius of classical proportions. The system is there for you to pick up. You just need to look.

For a simple primer, read Chitham’s The Classical Orders of Architecture, or Ware’s American Vignola. Or watch Texas’s own Brent Hull on YouTube.