Design for a Changing Climate

Reimagining the Courtyard House

Shipley Architects’ Courtyard House is a full experience for the senses. Everywhere you look, there’s something interesting to see, something that catches the eye and invites it to linger, observe, and understand. Sometimes the surfaces and details even dare you to touch and run your hand over them: the various textures, a handcrafted metal handrail, perfectly honed box-joints on the wood stair, or an inventive custom latch. The house asks us to pay attention to what we see, hear, and feel.

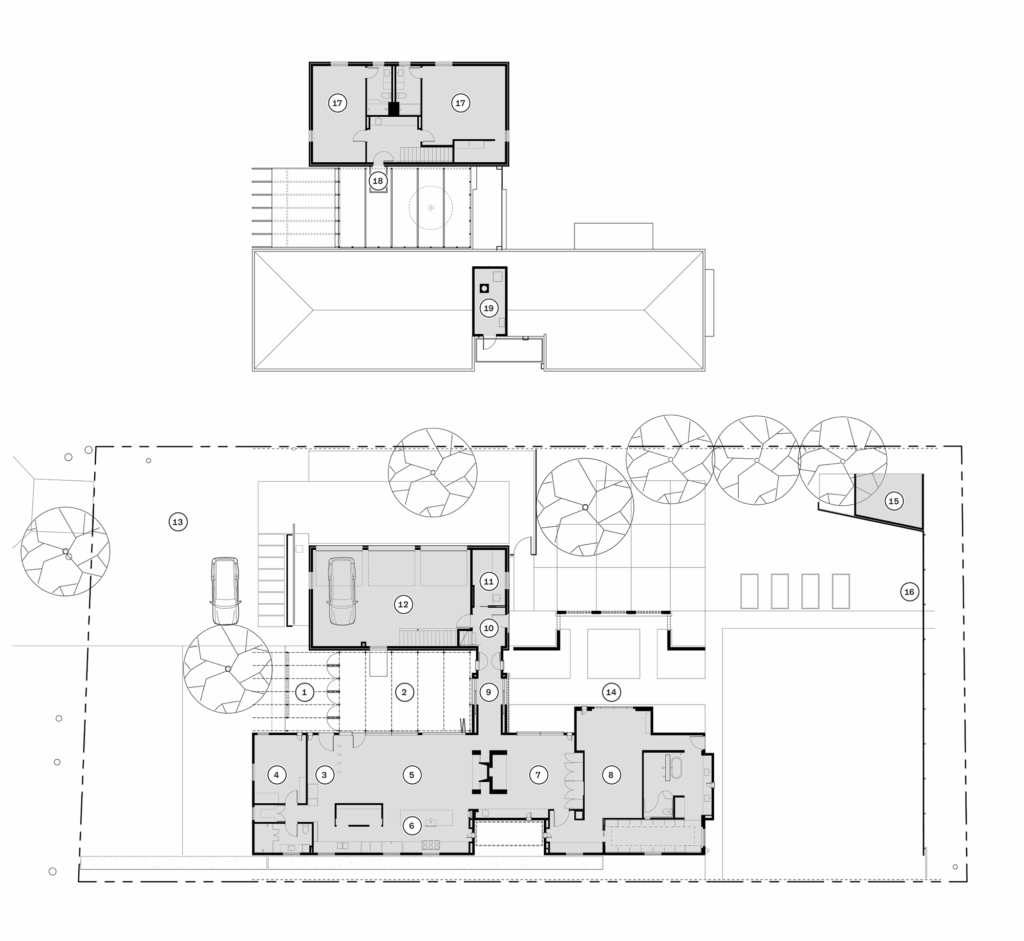

Located in the Bluffview neighborhood of Dallas and aptly named the Courtyard House, the residence unfolds around a lofted courtyard that serves as the introduction to the interiors. While privacy and restraint guide the exterior presence of the home, the courtyard embraces flow and openness. The space is a constant witness to the passing seasons, and breezes crossing through remind us that air conditioning is not always mandatory, even in Texas. This “in-between” courtyard—neither indoors nor fully outdoors—is filled with the sounds of birds singing and wind ruffling the leaves of the nearby trees. The geometric and colorful concrete floor tiles—crafted in the Dominican Republic—create a tapestry of intense hues, drawing the eye in and defining the space as the heart of the home. The experience of the courtyard awakens and grounds you in the best way possible.

The clients, Lynn and Tom McIntire, empty nesters and newly retired, sought a family house where their children and grandchildren would feel comfortable when visiting. Courtyard houses are not necessarily common in Texas, but Dan Shipley, FAIA, founding principal of Shipley Architects, thought that organizing the house around this tried-and-true model could be the answer to his clients’ goals.

The prototype of the courtyard house design has long been associated with Ancient Rome, where homes were typically organized around central atriums—open to the sky—that brought light in and structured the flow of living and working spaces. The courtyards in Roman houses also occasionally doubled as spaces for social gatherings and even for conducting business, which made them truly multifunctional and semi-public spaces.

The Courtyard House is a contemporary cousin of the Ancient Roman house. Here, the courtyard also brings light in and organizes the internal circulation, although in a less strict manner. It allows the house to be open but not transparent to the street, something the clients requested.

The courtyard is, inevitably, the focal point of the house, as it can be seen from most rooms. Interestingly, the McIntires also use the courtyard for receptions and other events. Large doors on the front porch can open the courtyard to the street, allowing guests to access it without entering the house. This immediately transforms the courtyard from a family space into a semi-public one—a perfect historical nod to the function of domestic courtyards in old Rome. Everything old is new again.

From the street, the house is organized in three volumes that flow from solids to voids and back to solids in easy patterns of brick and steel. The lowest, one-story volume to the south of the courtyard has the main living spaces: living room/kitchen, office, primary suite, and dining room. Curiously, a built-in day bed is part of the dining room, coyly suggesting lazy post-meal siestas. To the north, the two-story volume contains the three-car garage, utility room, and guest bedrooms on the upper floor. A land bridge connects the north and south wings of the house and delineates the eastern edge of the courtyard.

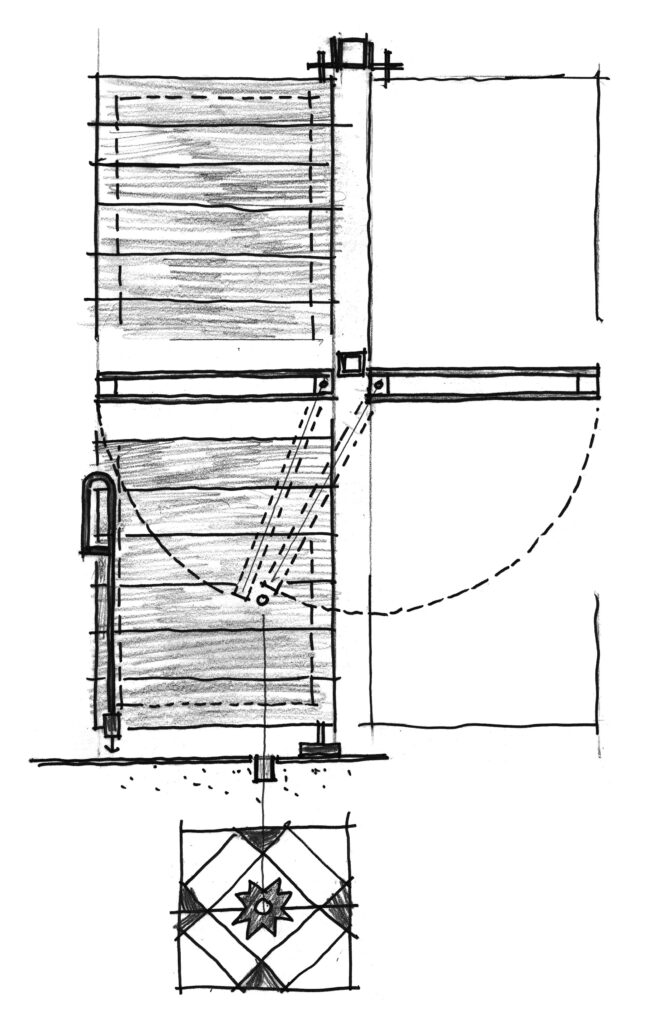

Design moves include a dramatic floating canopy topping the courtyard—the tallest of the three massing elements visible from the street. The very light structure rises up delicately in a pattern that is parallel to and reflective of the rhythm of the adjacent trees.

“The structure is made up of very small pieces, even smaller than the limbs of the Live Oak tree by the entrance,” says Dan Shipley. He is an architect who thinks like a builder. His drawings are sent directly to a shop for fabrication, erasing barriers between design and construction. In fact, Shipley primarily describes the house through the building process and its materiality.

Of note are the two types of brick facing the street: The house is clad in St. Joe, a molded brick from New Orleans, and a low wall next to the house is made of Old Texas brick from Mexico. Why two types of brick? The choice is deliberate. One is veneer, the other is structural; one plays protagonist and the other supporting actor.

Other examples of material dexterity include the main entrance, where the integrated bench-plus-coat-closet in Sapele is a sculptural custom piece of built-in furniture, a virtuoso exercise in cabinetry technique. Next to it, the freestanding pantry acts as a major organizing volume in the living space. Made of quarter-sawn oak, its modulation reconciles its own internal logic with the overall organizing grid of the house, making it unique and specific to its location. Also by the entrance, a sequence of recycled heart pine columns is made of imperfect wood twisting organically in sections and then realigning with the overall orthogonal order at the attachment points. In the living room, powder-coated aluminum sheets clad the prefabricated fireplace, giving it an unexpected sheen and texture.

Materials such as wood, ceramic, cork, and wool carpeting are used on walking surfaces, each chosen according to use and to reinforce the unique character of a space. For instance, cork tiles are used exclusively on the land bridge, and wool carpet is used in the main bedroom.

Spending time in the McIntires’ Courtyard House makes you aware of your place and time. Rather than isolating you, the house brings you into the here and now as it asks for your full attention. Not only is what you see captivating—which is the baseline for good architecture—but so is what you hear and feel as you move through the spaces. The senses are engaged, almost heightened.

The home invites you on a journey through both subtle and obvious juxtapositions, elegantly choreographed—lighter and darker, taller and lower, open and enclosed, compressed and expanded. This sensorial experience elevates the house from good architecture to something exceptional: a place for living fully. The McIntires, their children, and their grandchildren would surely agree.

Eurico R. Francisco, AIA, is a design principal at Perkins&Will and a contributing editor to Texas Architect. Originally from São Paolo, Brazil, he has called Texas home for 25 years.

Design for a Changing Climate

Shaping the Culinary Experience

Modern Hospitality Meets Cultural Legacy

At the Intersection of Neuroscience and Design

Snøhetta Transposes the Borderland

Designing for Neurodiverse Students

These finishes and furnishings focus on the power of color to influence mood, productivity, and overall well-being.

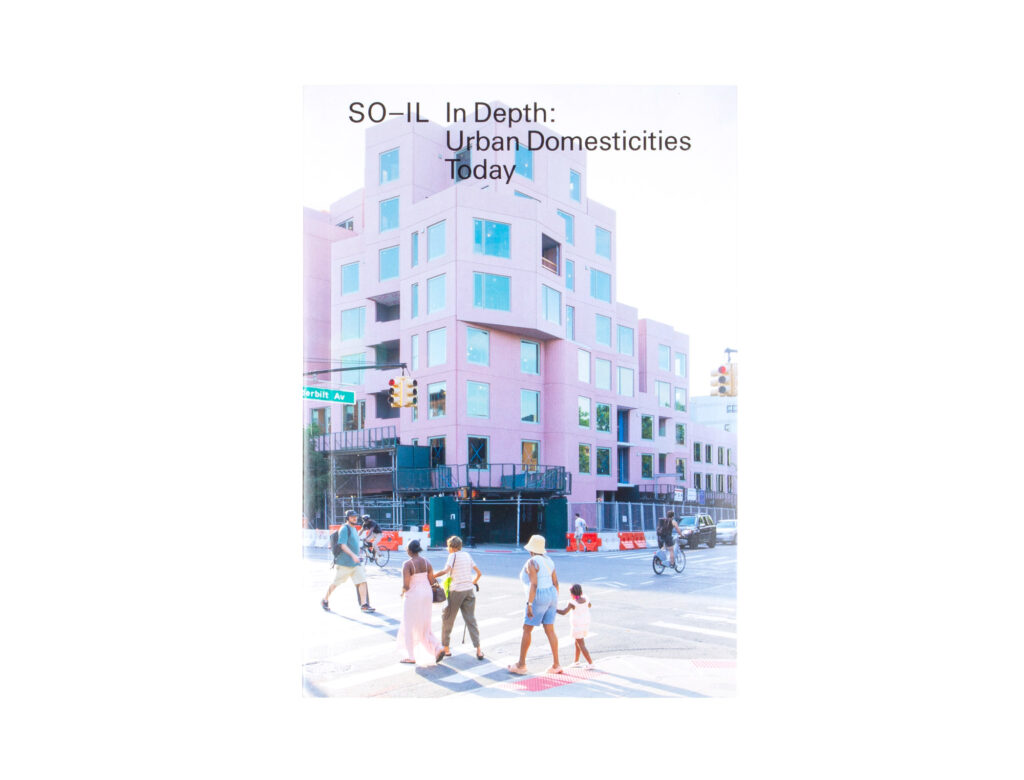

In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today

Edited by Florian Idenburg, Jing Liu, et al.

Lars Müller, 2025

Concrete Architecture

Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024