Reimagining the Courtyard House

Design for a Changing Climate

You are hiking in the woods. The smell of pine and juniper rides on the wind. Crossing a rocky clearing you find you must steady yourself with your trekking poles. You stop for a moment to take in the rolling hills, which are blanketed in trees as far as the eye can see. The silence is profound; all you hear is your breathing and the call of a nearby bird.

Or you are at the beach, returning from a swim. With your skin still drying and salt on your lips, you lower yourself face down onto a towel. Closing your eyes, you listen to the surf. You can smell the towel. The cries of seagulls and of children-not-your-own come from far away. As the wind wafts across your back, the warm sand beneath you begins to feel like a bosom: Mother Earth’s. Together you roll through space.

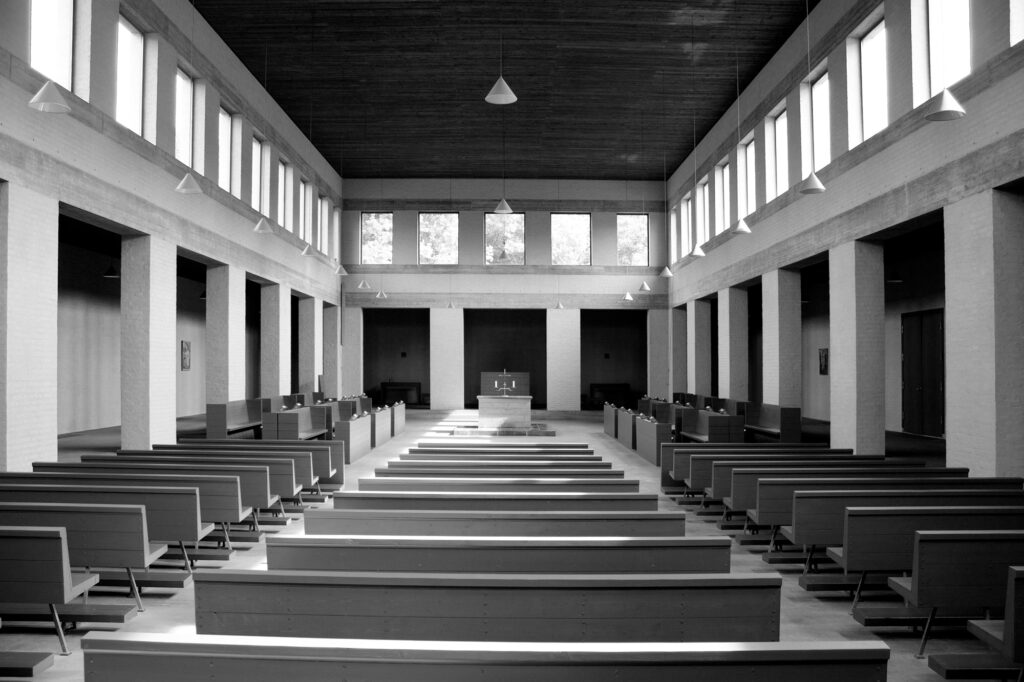

Why do scenes like this come to mind when thinking to celebrate the senses? Because it’s when our bodies feel pleasurably connected to the natural environment via all the senses—vision, smell, hearing, touch, taste, temperature, balance, duration, and orientation—that we feel wonderfully alive. Wanting to feel more alive is, in large part, the reason we engage in outdoor sports and adventures. It’s also why architects are periodically urged to go beyond the visual and photographic impact of their work and pay attention to how buildings address all the senses. The best buildings don’t just look good, after all; they feel good, sound good, smell good. The quality of the air is good too, and you want to touch them. My generation remembers reading Steen Eiler Rasmussen’s Experiencing Architecture; younger generations, Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin. Both books urged attention to the non-visual senses and took the richness and naturalness of outdoor experience as the gold standard. True, there are sensory pleasures to be had indoors: the smell of bread, the crackling of a fireplace, the softness of a bed, glorious concert halls, pounding dance clubs. But elements of buildings like broad sliding doors opening onto terraces and greenery, like winding balletic stairs, like skylights ushering sunshine onto stone…are more permanent, providing both actual access to and virtual “capture” of the Great Outdoors.

“Blurring the boundaries between inside and out—.” How often, dear fellow architects, do we use that phrase with pride as we claim that we’ve done it? The reason we do so goes back to the beginnings of the Modern movement: think of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium, Mies’s Farnsworth House. Back then, it drew justification from the health benefits of fresh air and sunlight, of cleanliness and exercise. The congested, noisy, rapidly industrializing cities of the time provided none of these things. Today we want health too, of course, but also to feel good in the sense of being alert and attuned to the world. The trick of everywhere “blurring…inside and out—” seems to accommodate that desire.

It leads, further, to the idea that architecture itself can and should be thought of as modified landscape and so is best when long-viewed, spatially open, decentered or many-centered, traversable, and transparent; best when continuous with or “made by” the site; best when creating various “conditions for inhabitation” instead of discrete rooms.

This ideal, alas, eliminates countless other perfectly desirable architectural “conditions,” like rooms with doors, windows, and shutters, like cloisters around courtyards, like cellars and attics fragrant and useful, like places to be in for a while, to dwell, dream, and work. Can one not feel sensorially alive in such places too? Can a building not be a refuge from the “great outdoors” and a delight? Of course it can. We need to think again about what the unique sensory qualities of indoor space could be. Why “again”?

“It’s when our bodies feel pleasurably connected to the natural environment via all the senses—vision, smell, hearing, touch, taste, temperature, balance, duration, and orientation—that we feel wonderfully alive.”

Let us go back and ask how good a job we are actually doing of “bringing the outdoors in,” of “blurring the boundaries…” and so on? The truth is that energy codes and client expectations tend to create buildings that are in fact climatically, thermally, and acoustically sealed. And we feel it all too well. Walls of glass have few or no opening sections, while sliding glass doors—those icons of modernity—remain closed but for a few days a year, moved briefly to allow entry and exit. If you work in an older building, chances are that the windows are nailed shut so as not to upset the HVAC. “Conditioned” air is injected into rooms via hidden ducts and pipes, as are hot and cold water. Waste is spirited away. Light is supplied by “fixtures,” while energy strong enough to kill large animals is ready to surge out of “receptacles.” Floors are smooth and flat: No balance or care is needed to cross them. How unnatural.

Are we finally living in “machines for living in”? In a way. Buildings today are more like bodies on life-support, bodies kept alive by conduits, tubes, ducts, pipes, cables, wires, and information-carrying infrared and radio frequency fields, all connected to sensors. That’s why power failures render them close to uninhabitable. In highly glazed buildings, moreover, we see the outdoors quite freely, which is better than not seeing outside at all, but we see out of them like fish in aquaria do: alive and mostly comfortable, but tactilely, motorically, olfactorily, and acoustically interred.

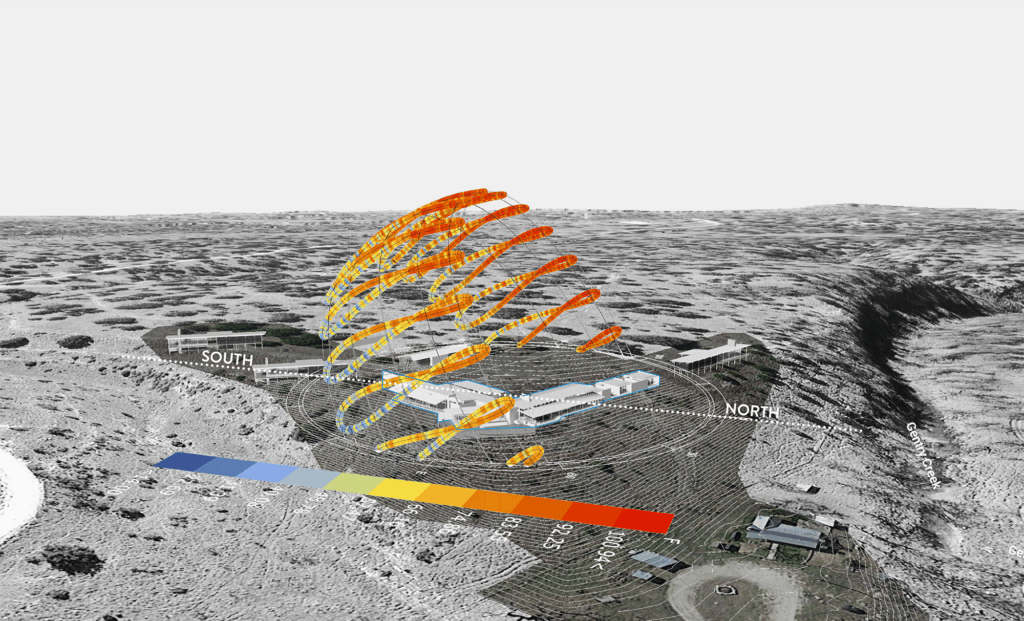

With climate change, sensory isolation from the outdoors is likely to become more prevalent and extreme in the developed world. Think Dubai. It’s only for a few weeks a year here, in Texas, that we can act as though we are living in Southern California or coastal Mexico, that we can leave doors open, sit outside, go for strolls, drive convertibles with the top down, dine “al fresco” in temperate comfort. Our nicer houses speak of this condition undyingly. By 2075, however, those happy weeks might be reduced to mere days. Average summer temperatures will be around 105°F, reaching 120°F in the afternoons. If the drought continues, most of Texas will look like West Texas does today, and West Texas like Death Valley, with highs around 140°F. Will we air-condition? Absolutely. For survival. But R30 insulation for walls and R60 for roofs will likely be legislated; windows will be triple-glazed and limited in area (perhaps to 20% of floor area). No single-wythe “curtain” or shop-front glass walls will be permitted; airlocks on all outside doors will be required. Rainwater collection and grey water recycling will become mandatory. Shade structures at civic scale will need to be provided. Indeed, shade will be considered necessary infrastructure, a public utility, prerequisite to development. Also needed will be public cooling stations set at prescribed intervals and enormous, slow-moving, wind-making fans. Open water will be treasured and also shaded. Some institutions will move their facilities underground, and many activities, like shopping, schooling, and sports, wanting to be outdoors, will become nocturnal. Texas’s inland towns will have grown quickly because of migration from Gulf Coast cities flooded by rising sea-levels, sinking ground, and ever-more-frequent hurricanes.

Global warming over the next 50 years will present enormous economic and political challenges—and not just to Texas, of course. Here we are examining one small such challenge, namely, a change in the sensory balance of life, a change in the texture of daily experience as mediated by the designed physical environment.

In that context we can be sure that people will depend ever more fully on networked digital media. People will have two or three handheld devices with general artificial intelligence (GAI), everywhere and at all times. Cheap LED screens—large and small, inside and outside, flat and curved—will mask most architectural forms like camouflage while our ears fill with non-local music, voices, and aural atmospheres (for a glimpse of this, see the Sphere in Las Vegas and the work of Refik Anadol). The senses can be occupied by things other than real places or real people, and quite happily occupied with the aid of pharma. Living substantially underground would more or less require such sensory diversion, Paolo Soleri’s amazing arcologies notwithstanding. A more realistic vision is provided by Philip K. Dick in his 1964 novel The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, which portrays life on a hot, largely abandoned Earth, as well as life “off world,” where colonists living mostly underground regularly and ritually escape into drug-and-media-induced, shared hallucinations of Earth’s better days.

You may find my reference to science fiction unnecessarily alarmist. My purpose is not to create apprehension but is twofold: first, to help prepare our profession for a future that may indeed be more stressed and artificial than we expect, and second, to consider how much of the world’s present sensory richness should be preserved. What of the smells not just of food, but of pantries, closets, garbage cans, steaming showers, medicine chests, wet cardboard, garages? Open a window, which it is still possible to do. Feel real air on your skin. Hear neighborhood music, voices, birds, and traffic, maybe the clatter of construction, and, at night, crickets and distant dogs and perhaps the wail of sirens. Worth keeping? In cities we can still catch the scent of winter smoke or of strangers’ cooking; in the suburbs, the scent of cut grass accompanied by the drone of lawnmowers, the spitting of sprinklers, and later, the scraping of rakes and roar of leaf blowers. If we cannot preserve these sensory experiences, will we try to simulate them?

Certainly, if bringing the outdoors indoors is worth doing, then it is worth doing beautifully, both now and in the future. Similarly, if taking the indoors outdoors is valuable, then it too deserves poetic execution both now and in the future. There’s no need to “blur the boundaries between inside and out—” with acres of glass; indeed, these boundaries could be made realer and more poignant while the worlds they distinguish, indoor and out—, are superposed, reappearing in some form, on both sides. This double superposition is not easy to pull off, to design well; it requires a process of sensitization, argument, and real-world testing that will take many years.

We would start the process by appreciating more deeply the effects on our psyche of actions like spreading a picnic blanket on a meadow in just the right place (what art!), of cupping our hands around a lantern in a wind-battered tent (how memorable!), of gazing at the stars though the hardly existent “roof” of a handmade sukkah having just eaten grapes (how grateful!). As architecturally schooled designers, we should admire upholstered sofas arranged confidently outside in lofty, arched patios beside lush, walled gardens (think Architectural Digest in Puerto Vallarta) and recognize the pathos of the patio chairs, umbrella, griller, and gazebo, usually forlorn in our backyards, but which today, in the late afternoon, children are excitedly arranging in order to make camp—yes, camp—overnight “by themselves.” And let us enjoy, or remember, or imagine, how wonderful it is to shower outdoors without concern for privacy.

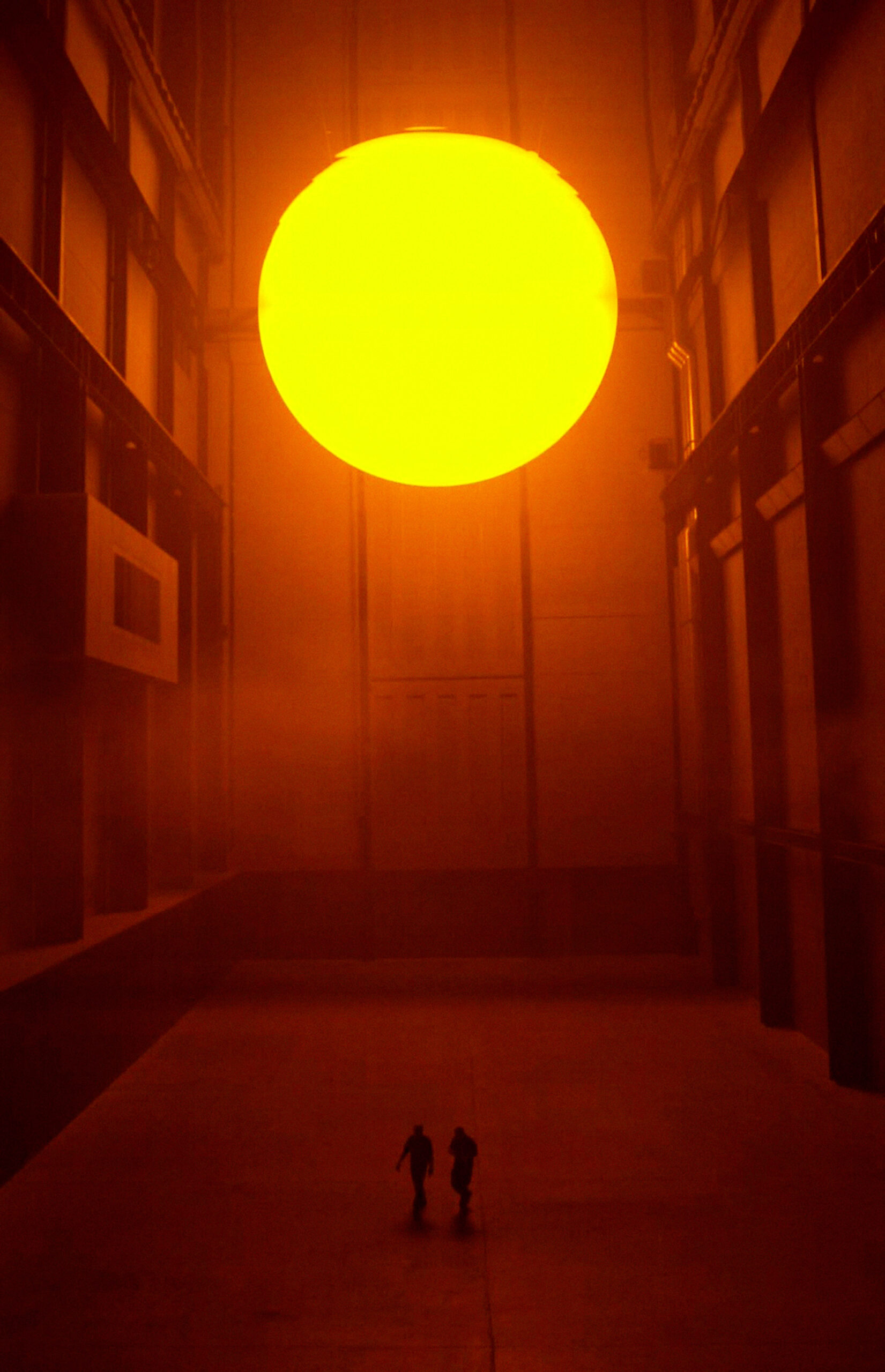

If this is bringing normally interior activities outside, what of the reverse—bringing outside experiences indoors? We touched on the effect earlier and will again below in more professional, architectural terms. In the meantime, let us not disparage the longing expressed by indoor plants, caged birds, water fountains, standing fans, mirrors near windows—windows whose curtains might move in a breeze. Let us look kindly upon naïve landscape paintings, coffee-table nature books, flower arrangements on sideboards, and avocado seeds and herbs sprouting on kitchen windowsills or mini greenhouse-like “garden windows.” Weather thermometers, globes, binoculars, driftwood sculptures, bowls of seashells and geodes, wicker furniture, wooden shutters, screened porches, humming-bird feeders, rain chains…these familiar, and yes, kitsch objects make it quite clear: Our senses want us outside, in paradise.

What to do, then, in preparation for 2075? Come massive climate change as predicted, or not, either way: How can we give our senses what they crave without resorting to kitsch? How can we create a sensorially richer, need-responsive, and beautiful architecture in that warmer future, starting now? Consider the following, quite concrete suggestions.

1. Coherent air conditioning

Several lines of present-day research are aimed at making air-conditioning more efficient: solid-state thermoelectric convection systems, geothermal heat exchangers, super-reflective roof coatings, and more. By 2075 we can expect a 50% improvement in HVAC energy performance, which will be great. However, none of these technologies address the way air moves through a building, which at present is very unnatural. We can do better than inject streams of very cold (or very warm) air via small, noisy “vents” into large bodies of air. Let us provide more wind-like coherent or laminar flow throughout a building. Buildings do not need air ducts snaking above their ceilings and up cavities because buildings are ducts already. Large, quiet, low-velocity fans can draw air through an entire structure, while perforated, positively pressured walls can provide broad, low-turbulence, horizontal flows across entire rooms. Treating a building’s interior as a problem in aerodynamics puts us in uncharted territory. Done well, the result would feel more natural on the skin (more like outdoors), save energy, and launch entirely new interior organizations and aesthetics.

2. Acoustically transparent windows

Windows with opening sashes and sections need only be opened a crack to let considerable sound through with minimum air transfer. In the future, high thermal performance windows could incorporate purpose-made, openable/closable slots in their frames. These might be visible or concealed. Alternatively, microphones outside can be paired with volume-controlled loudspeakers inside at every window. This done everywhere, the building would become acoustically linked to its larger environment, helping all its inhabitants stay temporally and geographically oriented. Windowless and underground buildings, of which there may be many more in 2075, would benefit especially from this technique. Finally, referring back to (1) above, open windows were once where outside air came in and interior air exited. Should future windows need to be sealed, however, conditioned air should be introduced only near them—say in the panels below or above them. Indeed, air and sound handling both could be part of the window package.

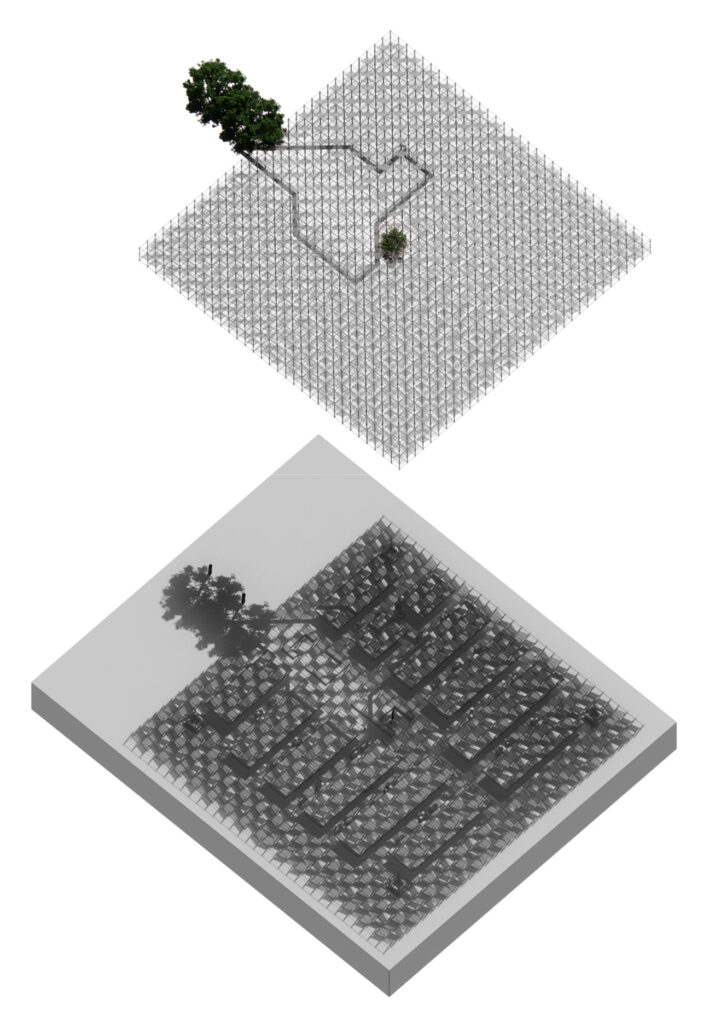

3. Incentives to provide outdoor shade

Presently, the real-estate value of covered outdoor space is 50% to 75% less per unit area than conditioned indoor space. Open, uncovered landscape is valued even less. Apartments with useful balconies are rarely being built: There’s more money to be made expanding buildings to their legal lot lines and using the thinnest permissible walls. Publicly accessible sun- and rain-sheltered spaces like market sheds, covered sidewalks, closely treed plazas, and fields of fabric canopies (in parks, on beaches) are rare in the US, although beloved when visited in the rest of the world. Now, it is possible that in a warmer future Americans will want to stay cool indoors even more and will value conditioned space more highly than they already do, even at the price of sensory isolation. Left to the market, the result would be a world of fully inflated, hermetically sealed, private buildings, with nothing but sun-blasted empty space between. Large parts of the world already look like this. If this is not what we want for 2075, there should be options, such as public funding for public outdoor space and percent-outdoor-shade requirements for developers. There is an art to making shade interesting: Shade is volumetric and partitionable by shafts and “walls” of sunlight. Shade moves; it has textures and quality. Then, too, wind need not be waited for but generated by large, slow fans, some misting, some blowing across bodies of water. In some places there could be hollow towers, wide enough to be under, and tall enough to use convection to pull cooler air down.

4. Kinesthetic planning

Among our most important senses is a bundle called kinesthesia: the feeling of our joints rotating and our muscles working, the feeling of spinning or accelerating (as judged by our inner ears), an awareness of gravity and of the changing patterns of friction and impact on our bodies. All these stimuli combine to tell us what we are doing, what shape we have taken, and how big we are. Indeed, a large part of our 3D vision is devoted to looking at our own bodies (especially our hands) and to planning and predicting how our bodies are going to feel as we negotiate the physical world. Now, among architects’ most accepted mandates is to minimize the amount of space devoted to circulation (usually meaning unassisted walking from A to B). Efficiency is the name of the game. And yet one of the ways we measure how much space we are in is by how much, and how far, we actually walk in it. It’s as though our bodies had fool-able planimeters in them. Too little circulation—too little kinesthetic stimulation—in an apartment, say, will make it feel smaller and more cramped. When built space is expensive for any reason, including climate-ameliorating technologies, it would behoove architects to extend rather than condense circulation. There will be optima to be sure, and trade-offs. The research to determine what those optima are remains to be done.

This essay began by explaining why architects are periodically urged, as in this issue of Texas Architect, to consider all the physiological senses rather than just vision. It’s because we feel most alive when all of our senses are stimulated simultaneously, which they usually are when we are (voluntarily) outdoors and in nature.

In the end, the challenge before us is not merely technical—it is emotional, philosophical, even existential. Architecture is ultimately about shaping the quality of life. If the climate forces us to retreat further indoors, to insulate and isolate, then we must ask: What kind of inner worlds are worth retreating into? The answer lies not in simulating the outdoors or endlessly reproducing its imagery, but in honoring the full complexity of human perception and memory. To build well in the decades ahead is to awaken the senses, not silence them; to craft spaces where the textures of life—of air and light, of sound and stillness, of motion and repose—can still be felt deeply and meaningfully. Let us not strive to escape nature, nor merely echo it, but to translate its richness into architectural forms that sustain both body and spirit. That is the real task for 2075—and it begins now.

Michael Benedikt is ACSA Distinguished Professor of Architecture and Hal Box Chair in Urbanism at the University of Texas at Austin.

Reimagining the Courtyard House

Shaping the Culinary Experience

Modern Hospitality Meets Cultural Legacy

At the Intersection of Neuroscience and Design

Snøhetta Transposes the Borderland

Designing for Neurodiverse Students

These finishes and furnishings focus on the power of color to influence mood, productivity, and overall well-being.

In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today

Edited by Florian Idenburg, Jing Liu, et al.

Lars Müller, 2025

Concrete Architecture

Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024

What a parting message!—a typically towering piece of intellectual thought and articulation by the distinguished (and recently deceased) Michael Benedikt. (He died on Aug 12, 2025.) It merits at least a few more reads…

Thank you for publishing this, TA.

May his memory be a blessing.