How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

How Can Utopic Ideals Be Engaged in Everyday Life?

It is neither wealth nor splendor; but tranquility and occupation which give you happiness.

— Thomas Jefferson

— Octavio Paz

Modernism is the expression by individual human beings of how they will live their own present, and consequently there are a thousand modernisms for every thousand persons.

Nobel Prize Reception Speech

Discussing the relevance of utopia in contemporary life may seem like a first-world privilege, yet the idea of utopia has persisted through various eras and cultures. The origin of the word dates to 1516 from a book of the same name by Sir Thomas More, predating our contemporary divisions of first, second, or third world. Numerous utopian movements and societies have existed across time and around the globe: Palmanova, Venice, Italy, 1593; Royal Arc-et-Senans, France, 1779; and Penedo, Brazil, 1929, to name a few. Most aspired to create societies and establish communities where ideals of egalitarianism and a particular form of cultural order were sought, even if they were not explicitly defined as “utopia.” Analysis of past utopian societies indicates they found direction by looking “backward or forward,” writes Tom Hodgkinson in his 2016 BBC article “How Utopia Shaped the World.” “They celebrated an old-fashioned ideal of community or envisioned a future paradise where the machines did all the work.” A social scientist, however, is not required to validate the failure of overarching utopian visions. These utopic experiments typically met their demise due to consequences of the original vision: incomplete or inadequate planning, rigid top-down organizational structures, the vision being undermined by a hyper-socialized engineering of individual lifestyles, or the gradual dilution of the vision’s value over time.

Considering the pressing need for positive discourse and cultural advancement in today’s world—fraught as it is with a decidedly non-utopian increase in social division, confusion over what is true, and normalized political conflict—credit is to be given to the editors of Texas Architect for proposing an exploration of utopia’s value in relation to lives, livelihoods, and design today. Due to the societal transformations, economic improvements, and increased personal autonomy that have occurred in the United States and beyond since the end of World War II, it is now possible to explore the experience of “utopia” on a more individual level, as opposed to earlier, collective interpretations that were tied to larger social or ideological constructs. As society and architecture evolve to respond to increasingly diverse and unique perspectives, it is only logical that the defining characteristics of utopian ideals should be recalibrated from collective visions toward more individualized experiences that reflect today’s socially atomized world.

Before exploring what a “modern” utopia might represent in relation to individuals and, in turn, to architecture, it is appropriate to define its boundaries. Two come to mind. Thomas Jefferson, architect, author, inventor, and president, speaks to a fundamental type of utopia— happiness—and structures it in a very personal manner defined by tranquility and occupational pursuits. A different boundary is identified in the presentation Mexican poet and philosopher Octavio Paz gave during his Nobel Prize for Literature acceptance in 1990. In it, he suggests that modernism is a compendium of how individuals “will live their own present.” What can be more utopian than everyone following their individual paths toward fulfillment?

The profession of architecture is well situated to respond to both Jefferson’s and Paz’s defining themes of an ideal nature. Involvement in an occupation that permits explorations of art, technology, science, and social/cultural issues, among others, as a part of its ethos is not a bad gig, if, as Jefferson suggests, wealth and splendor are not key components of a utopian equation. Similarly, Paz’s definition of modernism as a compendium of individual activities relates to a utopia achieved through the freedom allowed via the diverse and individual pursuits that animate much of modernism and modern architecture.

But what about examples of utopia that are more “realized,” ones that users and society actually experience? Two notable recent examples are Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti and the Seaside community by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, FAIA. These projects, though differing in their balance of occupation, tranquility, and individualism, both aim to create utopian destinations with similar goals, but they do so through radically different approaches. One remains largely conceptual, while the other is fully realized.

Arcosanti, located less than 100 miles north of Phoenix, Arizona, incorporates two primary themes—complexity and miniaturization—as strategies for constructing a utopian live-work environment and identified by Soleri in his book Arcosanti: An Urban Laboratory? Originally conceived in the late 1950s, with construction beginning in 1970, Arcosanti represents a critique of city planning based upon an approach to urban design that is similar in spirit to the founding principles of New Urbanism, whose themes are articulated in Florida’s Seaside community. In planning Arcosanti, Soleri wove together multiple public destinations with adjoining residential districts to create a more compact and walkable town, to the point of excluding cars.

Soleri’s vision of “arcology”—combining architecture and ecology—can be appreciated as an early foray into sustainable urban design, emphasizing density and ecological strategies. Architecturally, it aspires to celebrate communal living by integrating abundant public gathering spaces and to minimize sprawl by condensing residential domains. Originally planned for a community of 5,000, it has continued to develop at a slow pace for over 50 years, with a current population of around 150 residents primarily engaged in activities focused on light manufacturing, workshops, and tourism. Its lackluster growth is the result of Soleri’s top-down thinking, which overlooked various externalities including its remote location, overreliance on unpaid labor, and his own demonization of the automobile. These were coupled with an overly socially engineered approach that did not allow for flexibility or options.

Seaside, though contrasting with Arcosanti in many ways, shares some key attributes. Built along Florida’s panhandle next to the Gulf of Mexico (construction began in 1981), Seaside suggests a utopian vision that aligns with ideas from Jefferson and Paz, despite its more traditional appearance. Its scenographic tranquility is partly achieved through the exclusion of certain programmatic elements, like industrial facilities and essential services, forcing inhabitants to travel to less idyllic destinations for the purchase of items necessary for living. This creates a “lifestyle utopia” achieved through a form of economic segregation, a feature common in many large-scale utopias, which tend to cater to specific economic, occupational, or value-based groups, limiting their appeal to a narrower audience.

“The orthodox version of utopia typically involves a significant rethinking of the world as we know it, with the intent to transform existing conditions.”

Although Seaside follows a unifying, rule-based design aesthetic rather than celebrating the individualistic style preferred by so many architects, it still reflects an aspect of Paz’s form of individualism. Its success as a utopian typology stems from Duany’s understanding that individuals, when given a choice of where to live, often choose towns over cities and suburbs. Combining a town-based aesthetic and an organization that privileges people over automobiles, the utopia once considered lost is regained in the form of a memory-based tranquility supported by the wealth generated by individual work occurring elsewhere, echoing Jefferson’s idea of happiness.

Arcosanti and Seaside are diametrically different both in concept and in their methods of creating utopian communities. The architecture of Arcosanti reflects its visionary, idealistic approach—as well as the liabilities identified earlier—while Seaside was generated, in part, through an aesthetic appearing more knowable, thus relatable, by incorporating manifestations defined by a compendium of idealized memories of design norms. Both share themes of successful living as defined by Jefferson and Paz yet achieve them through different approaches to densification, and both rely on exclusion—whether cultural, lifestyle-based, economic, or ideological—to establish their vision.

This recognition of exclusion as a feature of many realized and failed utopian visions led to possibly the most utopian of utopian visions—one not experienced but envisioned by Buckminster Fuller. Fuller advocated for a utopia based upon the “great transformation” of man’s physical capabilities through scientific industrialization, which would allow for “doing more with less.” Through a revolution in science and technology, he said, utopia could be achieved in the present day, not by extensively altering the conditions by which man lived but by “helping him to become literate.” Man could use his innate cerebral capabilities to at least achieve physical survival at a “utopianly successful level.” Utopia then, and admirably defined by Fuller in Utopia or Oblivion, “must be, inherently, for all or none.”

If Fuller’s idea of utopia represents the peak of the utopian project—one that includes everyone and benefits all—it is limited by being a generalization of what science, technology, and man can accomplish together. However, as an expression of Fuller’s ideal for humanity, can our profession develop design strategies to bring “utopianly successful” outcomes into everyday life, creating more tangible, foundational ways to enhance and anchor people’s daily experiences?

The orthodox version of utopia typically involves a significant rethinking of the world as we know it, with the intent to transform existing conditions. From a design perspective, could a reimagining of architectural utopias (aka agendas)—ideas often tied to larger movements or the “isms” that move regularly through our profession—shift toward micro-utopias? Instead of a radical change in our location or transformation of lifestyle, could we focus instead on creating utopian enhancements of our local environment and everyday experiences? Starting with small-scale improvements in how space is designed to elevate daily life could be a practical approach. Addressing fundamental areas of design, like materiality and lighting, could lead to better outcomes that can be experienced by all. This is because architects are chiefly organizers, and organization when imbued with intention can create an order that is more experiential, not just functional. Add ideas that connect to deeper representational concepts, and themes emerge that can lead to designs that feel more connected and impactful, offering new ways to experience and understand utopia in our lives.

While the term “order” is not referenced as often as it was in the past, its relationship to organization reflects a basic human need for stability, or as architectural historian and theorist Alberto Pérez-Gómez puts it, for “psychosomatic health.” After years of architects treating order as a form of normative coherence—focused on functionalism, structural grids, standardized material components, and other “correct” approaches to design—there’s value in rethinking how we define it. Design approaches legitimately centered on performance and economy can be expanded to realize more humane and graceful conditions that inspire us. Order and organization—when aligned with designs intended to free us from traditional ideas of grids, windows, and walls and move us into experiences where enriched expression of space, light, and materials lyrically reveal themselves—do provide opportunity for reimagined moments. This shift away from over-reliance on standardized solutions can lead to outcomes that do more than just “work” but that also inspire, creating moments of unexpected beauty and meaning.

A clear example of this is provided by John Patkau of Patkau Architects when he explains their interest in conceptualizing the use of light: “We intended (to use) light as if it was like the sun shining through a small clearing in the forest—otherwise one just has skylights.” Admitting light though skylights is certainly not an inappropriate design approach. However, conceiving the experience of light in the manner described for Strawberry Vale gets us closer to new ways we might craft experiences through organizational strategies and representational conceptualizations rather than through a standard understanding of light and similar phenomena.

Recent trips to Japan with architecture students from the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design have also provided examples of designs focused on light, materials, and space with outcomes that inspire and uplift. Chief among Japanese approaches to design include the concepts of ihyou and ma. Ihyou translates into design that elicits a feeling of surprise or awe, or expresses something that is seemingly impossible. Ma relates to space but more as an interval—a gap that adds meaning to the whole by creating a sense of place and possibility. In a sense, it builds on the intrigue we experience through anticipation, not necessarily completion. This contrasts with contemporary design approaches employing “industrialized” languages—standard organizations of standardized components that offer little to uplift the human spirit.

The presentation space of the Mokuzai Kaikan building in Tokyo, designed by Nikken Sekkei Architects, serves as an example of how a utopian vision might be successfully achieved through the re-envisioning of a space in a way that elevates the spirit. The space uses the concept of ma and, in its design, redefines the role of wood. A material that has too often been standardized and used in default applications, here wood is reintroduced as a medium of creativity and celebrated for its expressive and experiential qualities. A screening wall made of wood “sticks” serves as a backdrop that allows viewers to see both the forest and the trees rather than merely a panelized representation of these. This innovative use of wood transforms our perceptions of the wall into an expression of lines and space, challenging expectations and offering a new understanding of what a “wall” can be.

In their design of the Niijima Forest Chapel, Tezuka Architects reimagines one of the most prosaic of industrialized materials—plywood—into a celebration of illumination. Each plywood panel is perforated, allowing light passing through to act as pixels that collectively create an image depicting the Garden of Eden; the structural grid is transformed into a forest-like space augmented by the dappled light penetrating the metaphorical tree canopy. Similarly, two projects by Junya Ishigami for the Kanagawa Institute of Technology demonstrate design solutions intended to stimulate creativity. The institute’s website states: “KAIT Workshop is established to realize the hope and dream of making creative goods freely.” The workshop was conceived as an open “place to make creative goods in the woods,” its design forgoing internal walls that would separate the various components of the program. Utopian in aspiration, the realization of the workshop does inspire. One wanders from domain to domain through an indeterminant field of steel columns, sidestepping those that interrupt your path. At other times a spatial counterpoint is provided through an absence of columns—a “clearing.” The design elicits awe not only visually through spatial experience but also cognitively as one realizes that each of the 305 columns used to support the roof have a different orientation and size, with 42 columns carrying compressive loads and 263 post-tensioned, acting as mini shear walls. The workshop is indeed utopia experienced, both through a rethinking of space and material expressions and as a realized vision of a place of education.

Expressing an even greater ihyou factor through the reimagination of space, material, and light, though, is the adjacent plaza. Blaine Brownell, FAIA, director of the School of Architecture at UNC Charlotte, describes his experience of it, stating: “Stunned we gaze, transfixed at an otherworldly void.” Statements such as this suggest architecture’s ability to elicit experiences of a utopian level by reconceptualizing our designs rather than relying on proforma standardizations.

Embracing inclusive methodologies, such as ma and ihyou-like approaches, activates the human spirit and enhances experiential outcomes. By enriching natural phenomena like light and materiality through design, we evoke a utopian sense of awe, rather than diminishing it through reliance on standardized, conventional components. If a life well lived as defined by Jefferson and Paz is connected to an enrichment of our lived daily experience, the potential for utopian advancement emerges. Through design, let Jefferson’s ideals of happiness and tranquility be more fully experienced at our places of work and Paz’s insights on individual talents guide us towards Fuller’s call for utopianly successful design solutions enjoyed by all.

How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

An Ambitious Office Tower Redefines Urban Sustainability

Exploring the Perils and Delights of Houston’s Irreverent Approach to Urban Development

A Family’s Legacy of Excellence

Picture-Perfect Charm Along the Texas Gulf Coast

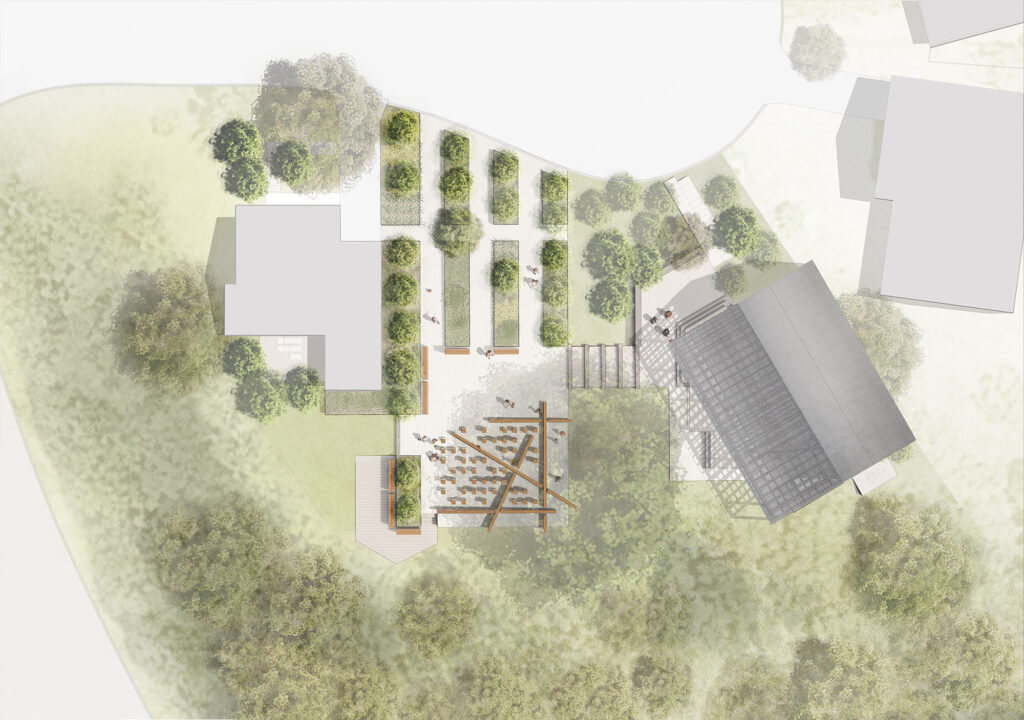

PS1200 Builds a Backdrop for Public Life

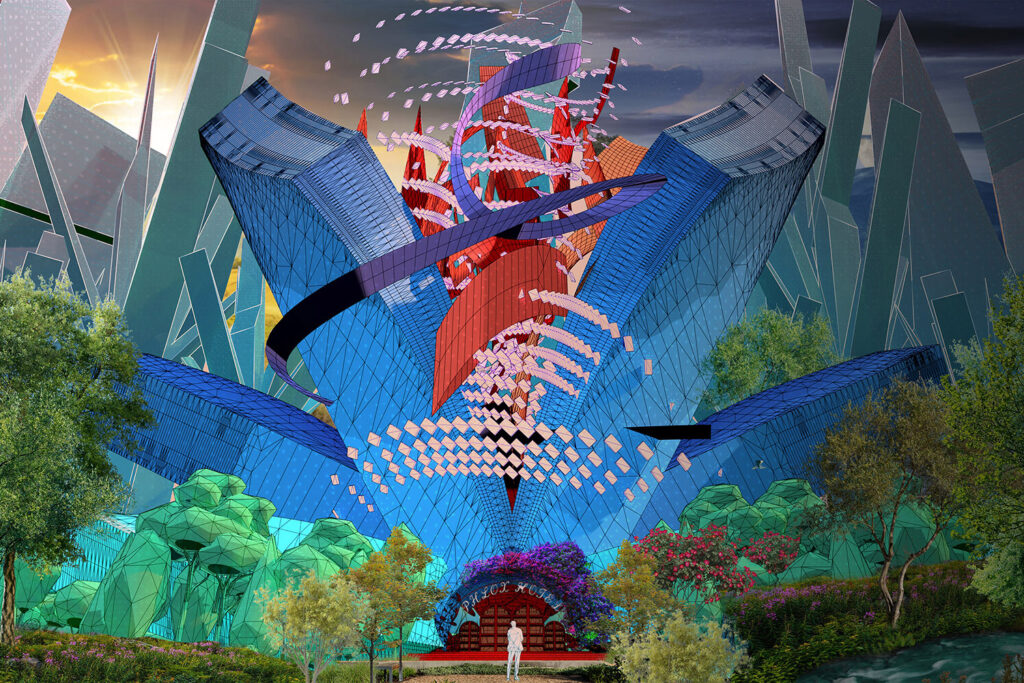

Exploring the Parallels Between Science Fiction and Architecture

Illuminated Wood Panels, Inserts for Brick Walls, and Fixtures Made from Recycled Plastic, Mycelium, and Hemp

Home, Heat, Money, God: Texas and Modern Architecture

Text by Kathryn E. O’Rourke

Photographs by Ben Koush

University of Texas Press, 2024

Big Little Hotel: Small Hotels Designed by Architects

Donna Kacmar, FAIA

Routledge, 2023

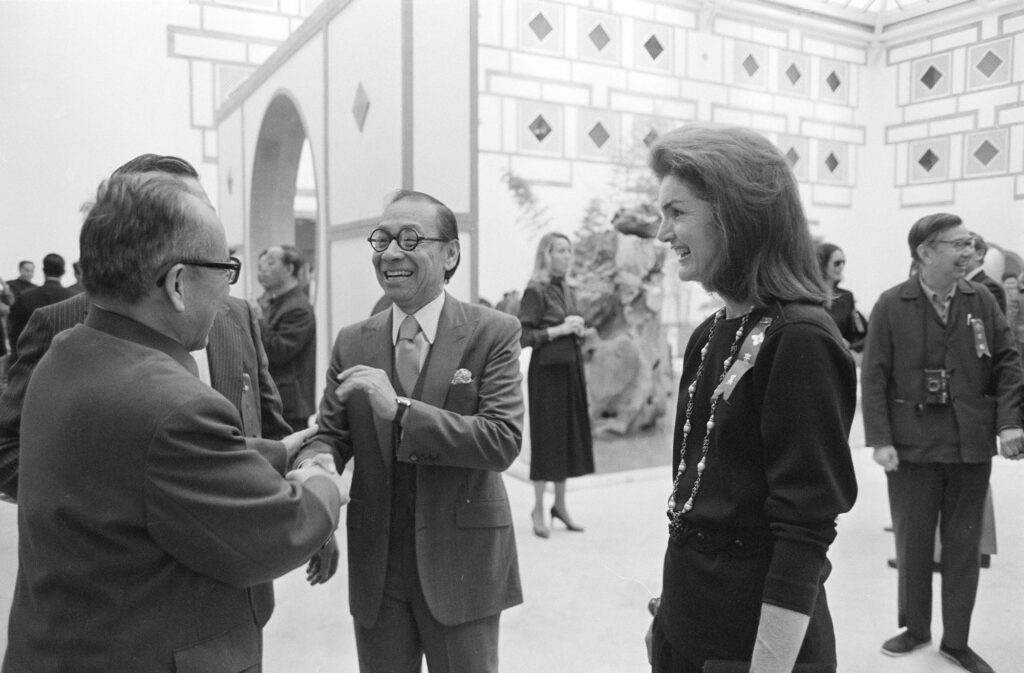

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture

M+ Museum, Hong Kong