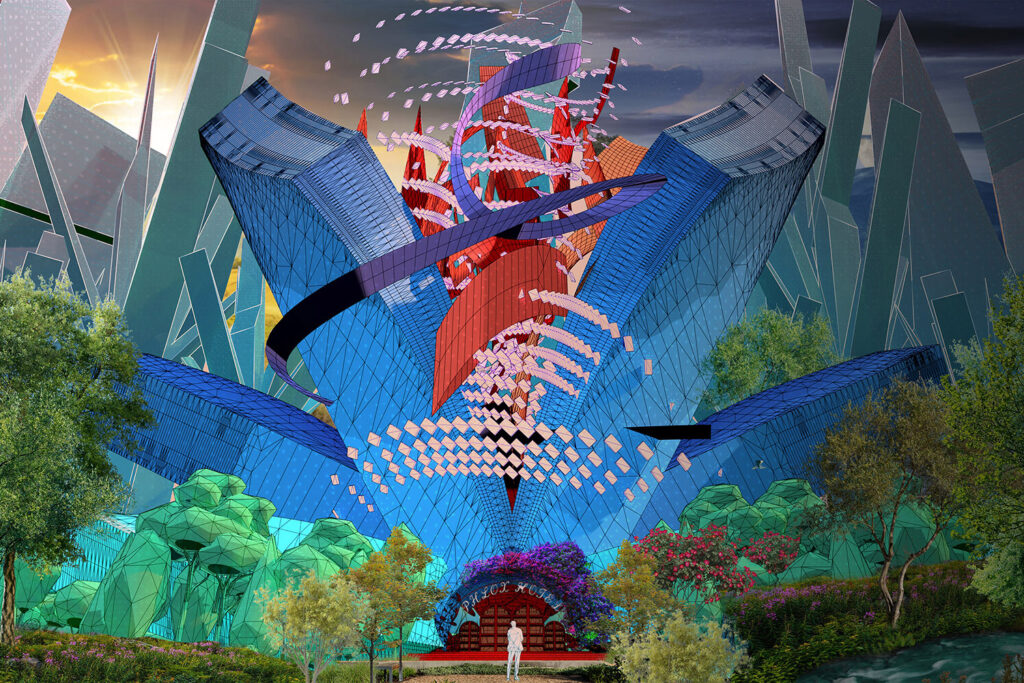

How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

Exploring the Parallels Between Science Fiction and Architecture

Somewhere just beyond our solar system, an asteroid is terraformed by a xeno-species we cannot recognize. Using an adaptive atmosphere held up by a network of super towers, the lifeforms create a flourishing ecosystem. What can we learn from them? Wild questions like these are at the foundation of the most gripping problems facing humanity, and our imaginations are the superpower we hold to solve them.

The merging of architectural visioning with narrative storytelling has the potential to go beyond provocative solutions to provide what the world needs most—inspiration. Writer and historian Cody C. Delistraty’s 2014 article in The Atlantic, “The Psychological Comforts of Storytelling,” traces the origins of narrative tradition as an evolutionary strategy that evokes empathy and offers a sense of control over a chaotic world by providing important instructional blueprints for survival. “Stories are a form of escapism, one that can sometimes make us better people while entertaining,” writes Delistraty. While communities here on Earth grapple with life-changing technology and climate shifts, architects are uniquely positioned not only to imagine better futures but to help make them a reality.

Dr. Johanna Nalau is a social scientist, an advisory committee member for the US State Department’s Increasing Climate Resilience via the Private Sector Investment project, and an adaptation scientist based at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia. She sees imagination as transformational. As part of the 2019 negotiations in Madrid for the Resilience Frontiers (RF) Initiative, a program for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that brings together eight key pathways to accelerate the world towards global resilience, she uncovered something astonishing.

Says Nalau: “We had a RF pavilion where we discussed ideas each day with a different theme. But [two questions were] always the same: ‘What does the world look like in 2030 and beyond if we fail?’ and then ‘What does the world look like in 2030 and beyond when we have succeeded?’” The first question examined dystopian visions of the future. Participants answered with comments about lack of water and ecosystem destruction, among other things. When she flipped the question to ask what the world would look like if humanity succeeded in finding balance with nature, the pavilion fell quiet. “I think, for me, the silence was not necessarily [because] people did not have ideas on how to take action on climate change,” explains Nalau. “It was more about [a lack of] collective imagination and the difficulties in seeing something bright and different in a conversation where often we focus on the failures and drastic outcomes.”

“Storytelling, for both scientists and architects, serves as a powerful tool to move beyond mere visioning of positive futures, enabling them to communicate more compellingly and accessibly with the public.”

Parallels can be seen between Nalau’s observation and the onslaught of the 24-hour news cycle and explosion of media streams feeding the public an endless supply of dire news and data. The human mind is a powerful tool for both imagining and drawing boundaries around what is possible. Nalau continues, “My research on climate adaptation heuristics (rules of thumb that we have developed about adaption) is very much focused on how we imagine something to be and how that often drives the decisions we make and options we think are viable.”

Architects engage with this concept by expanding and educating their clients, cities, and communities about the potential of design. Storytelling, for both scientists and architects, serves as a powerful tool to move beyond mere visioning of positive futures, enabling them to communicate more compellingly and accessibly with the public. Film and science fiction (sci-fi), in particular, act as cultural barometers—reflecting society’s hopes, fears, and evolving sensibilities. Nalau agrees. “It is the role of film and literature to open our imagination for different possibilities and maybe learn something also in the process about how we can handle the future.”

Houston environmental journalist, activist, and USA Today best-selling author Sim Kern explores an alternate reality in their 2023 novel, The Free People’s Village, which depicts a scenario where Al Gore won the 2000 presidential election, leading to a 20-year “War on Climate Change.” Kern explores economic contrasts through architectural concepts, juxtaposing suburban homes and rewilded front lawns with toilets imported from Japan, or green skyscrapers with private orchards made possible only by razing neighboring homes rather than retrofitting them. Says Kern, “There are solutions that are green on the surface, but when you dive more into it, you have to ask yourself, is this really sustainable?” The story follows an unreliable narrator named Matty who benefits from green infrastructure, carbon-cutting, and lush high-rises as she explores Houston’s fictional Eighth Ward. In a warehouse-turned-music-venue called “the Lab,” she falls into a social movement and experiment that changes the entire city.

“I breathed easier rounding the turn onto Calcott, spotting the Lab up ahead, silhouetted by the last of the sun’s rays. Light and loud music spilled from the old red-brick warehouses’s windows and doors, every hole in that lovely, ugly face thrown open, filled with people of every race, gender, style and subculture you could imagine, all of us so young—young enough to have no idea what kids we all were.”

—Excerpt from Sim Kern’s The Free People’s Village

The Lab starts out in the characters’ minds as a beacon of hope, a utopic place full of possibility and wonder. But the more they learn, the more they realize that a spectrum of utopias exists. “The Lab was inspired by a real place that I knew in my twenties,” Kern recalls. “It was a brick fourplex where they would throw shows and parties. We would skateboard inside and draw over the walls of this clubhouse that eventually fell into ruin and was torn down to make way for luxury apartments and townhomes.” Stories don’t need to offer a binary experience; the best ones challenge readers to develop new perspectives on the world around them. Understanding a range of viewpoints is essential for designing better places, and storytelling can shape the way architects engage with and communicate diverse ideas of what those places might be.

Utopia and its counterpart, dystopia, are common themes in science fiction. Utopias have long fascinated writers, as seen in the television franchise Star Trek, Aldous Huxley’s 1962 novel Island, and Jaroslav Kalfar’s 2017 novel Spaceman of Bohemia (later produced in 2024 as the film Spaceman directed by Johan Renck). These stories get to the heart of what makes science fiction so uniquely suited to imagining futures.

They depict places with expansive and iconic architecture, building on principles of awe and wonder, which have been prevalent throughout human history and architecture.

In the 1950s, author Ray Bradbury called science fiction, “the one field that reached out and embraced every sector of the human imagination, every endeavor, every idea, every technological development, and every dream.” As a genre, it conveys to the audience that there will be futuristic elements centering on science and technology in the story, but that is not necessarily what the story is really about. Speculative science fiction might feature alien species inhabiting the same world we currently live in, for example, but on a deeper level, it may actually be a story about free will, time, and language.

Notably, utopias are harder to find, and many stories that begin as utopias devolve into dystopias, providing plenty of examples of failures of both architecture and society. While few can easily imagine their own version of an ideal society—as seen in the groups from the RF pavilion—almost everyone can name a dystopian story that offers a bleak vision of the world.

Classic examples include Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, adapted into the 1982 neo-noir film Blade Runner by Ridley Scott. The film prominently featured iconic locations such as the Bradbury Building, designed by George Herbert Wyman, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House. According to the City of Los Angeles, Wyman’s design was inspired by Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel Looking Backward, which imagined a future of cooperative housing and shared workspaces organized around crystal courts. Wright’s, on the other hand, drew inspiration from Mayan architecture, exploring how it conveyed permanence, utility, and beauty.

More recent dystopian narratives, such as Alex Garland’s 2014 Ex Machina, continue to use architecture to reflect themes of wealth, power, and technological advancement. Filmed in a futuristic, minimalist setting—a merger of the real-life Juvet Landscape Hotel and Fjora House, both designed by Norwegian firm Jensen & Skodvin Architects—the location symbolizes extreme wealth and egotism in a world grappling with the ethical implications of artificial intelligence.

Climate fiction, or “cli-fi,” is a subgenre of science fiction that explores environmental crises and their impact on humanity. From J.G Ballard’s The Drowned World (1962) to Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993) and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006), these novels grapple with how people adapt to extreme shifts in the ecosystem. Johanna Nalau advocates for reading cli-fi to better understand the potential of environmental storytelling, citing Artificial Wisdom (2023) by Thomas R. Weaver as a prime example of the genre’s impact on imagining future possibilities.

In Weaver’s novel, a closed-door mystery unfolds within a globe-trotting thriller. The story follows UK journalist Marcus Tully, who investigates political intrigue surrounding the world’s first artificial intelligence, an “Artilect,” running against a human candidate for the role of climate dictator. This figure is tasked with steering humanity through an impending environmental collapse.

Weaver’s rich, cinematic descriptions immerse readers in a world set 25 years in the future. While many scenes, such as a London bedsit or a luxurious penthouse, remain grounded in contemporary architectural design, the novel also introduces fantastical settings—like New Carthage, a floating metropolis modeled on classical architecture. This city, enclosed in a self-sustaining dome, drifts across the globe, offering the wealthy a refuge from climate disruption. The dome creates its own microclimate, allowing its elite residents to maintain their lifestyles with minimal interruption. The name “New Carthage” and the classical design of its buildings evoke a sense of permanence and power, reflecting an effort to avoid dissent in an otherwise unstable world.

“Even the birds must have been imported, confined to the dome covering the island. He shook his head. It was too artificial here, too perfectly designed; a high-end, luxury hotel-village where everything was manufactured for the pleasure of its guests. But like any holiday, after a week you just wanted to be back in your own bed.”

—Excerpt from Thomas R. Weaver’s Artificial Wisdom

Architecture is sci-fi—defined by the unknown and driven by an enduring optimism for the future. The parallels between the field of design and the imaginative realms of science fiction offer fresh perspectives on how we can understand the built environment and integrate emerging adaptive technologies. From industrial warehouses in Houston to visionary floating cities, science fiction crafts intricate worlds that present new possibilities for addressing some of society’s most urgent challenges.

As the world grapples with the uncertainties of both the built and natural environments, science fiction may provide a roadmap for new solutions. Architects are increasingly drawing inspiration from sci-fi, while sci-fi writers are influenced by architectural concepts. More than mere backdrops to a narrative, science fiction worlds illuminate our humanity—our hopes, fears, and the enduring impact of the spaces we create. By viewing design as a form of storytelling, architecture can become a powerful tool for change—shaping more beautiful, resilient, and thought-provoking futures. In this way, the boundaries between architecture and science fiction blur, inviting us to imagine and build a world that is not only functional but also deeply transformative.

How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

An Ambitious Office Tower Redefines Urban Sustainability

Exploring the Perils and Delights of Houston’s Irreverent Approach to Urban Development

A Family’s Legacy of Excellence

How Can Utopic Ideals Be Engaged in Everyday Life?

Picture-Perfect Charm Along the Texas Gulf Coast

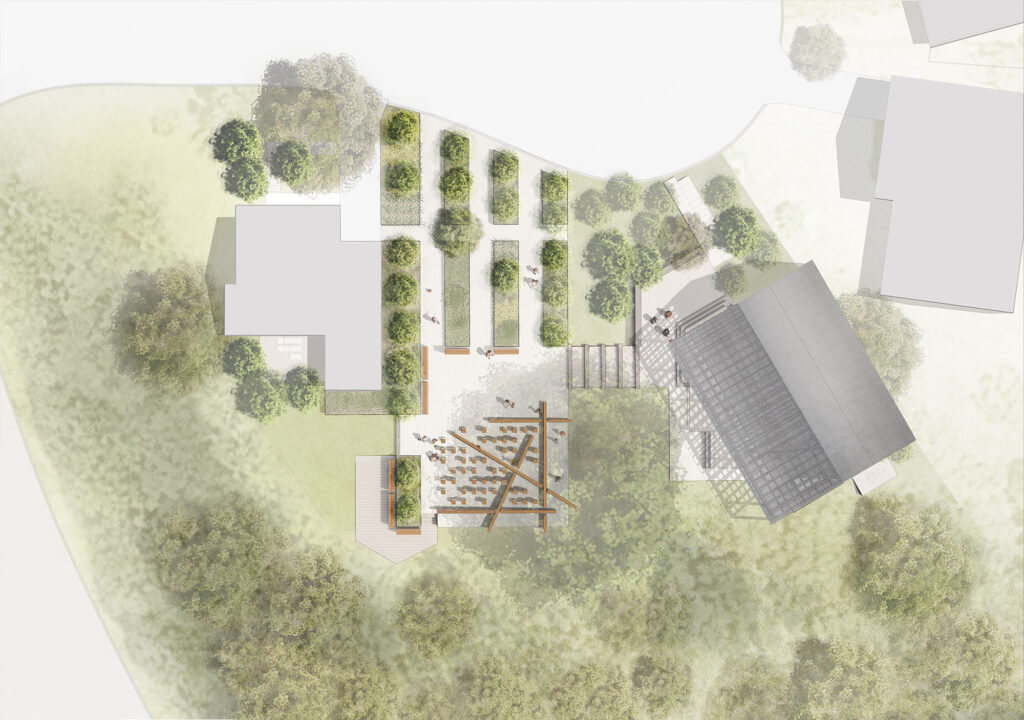

PS1200 Builds a Backdrop for Public Life

Illuminated Wood Panels, Inserts for Brick Walls, and Fixtures Made from Recycled Plastic, Mycelium, and Hemp

Home, Heat, Money, God: Texas and Modern Architecture

Text by Kathryn E. O’Rourke

Photographs by Ben Koush

University of Texas Press, 2024

Big Little Hotel: Small Hotels Designed by Architects

Donna Kacmar, FAIA

Routledge, 2023

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture

M+ Museum, Hong Kong