Zen Rose

Japanese design principles inspire an architect’s Glen Rose studio.

Project 110 Walnut Street

Location Glen Rose, Texas

Architect Jeff Garnett Architect

Design Team Jeff Garnett, AIA

Contractor J Kellam Builder

Structural Engineer HnH Engineering

Geotechnical Engineer CMJ Engineering

Accessibility Consultant Johnson Kelley Associates

Photographers Costa Christ, Tyler Ellison

After graduating from the UT Arlington School of Architecture in 2008, architect Jeff Garnett, AIA, spent his early career working in Austin, at Haddon + Cowan Architects and under legendary residential architect James Larue, AIA, who has perfected a unique modernist approach to Hill Country vernacular. After several years there, Garnett and his wife began searching for a more rural place to raise their young family and start his practice. They relocated to an old farmhouse outside of Glen Rose, the town Garnett had grown up in. He then established his solo practice in nearby Fort Worth in 2016.

Eventually, Garnett saw a need to set up shop closer to home and started searching for office space in Glen Rose. When a “for sale” sign went up on a coveted empty infill lot between a former Coca-Cola bottling plant and the Talley Building on the Glen Rose courthouse square, he knew he had found his kismet. Plans quickly got underway for a modernist intervention in the historic location, which sits directly across from the front door of the small Somervell County courthouse dating to 1893. To say that a modern design solution was met with skepticism by the local preservation board was an understatement. But, once Garnett carefully explained that views to the courthouse were to be framed through a large front window and how modest the limestone facade would be, he eventually won the board over, and the project went forward.

The project has been enthusiastically received by the historic preservation board and the public who either visit or do business on the courthouse square, one of most beautiful in Texas. Some in the local business community have been confused by the decision to narrow the interior space to one side to allow for a long and hidden entry court, much like a Japanese engawa, or side porch. This is because to achieve this unique entry feature, floor space was bravely sacrificed, which to the business-minded appears as a loss of commercial value.

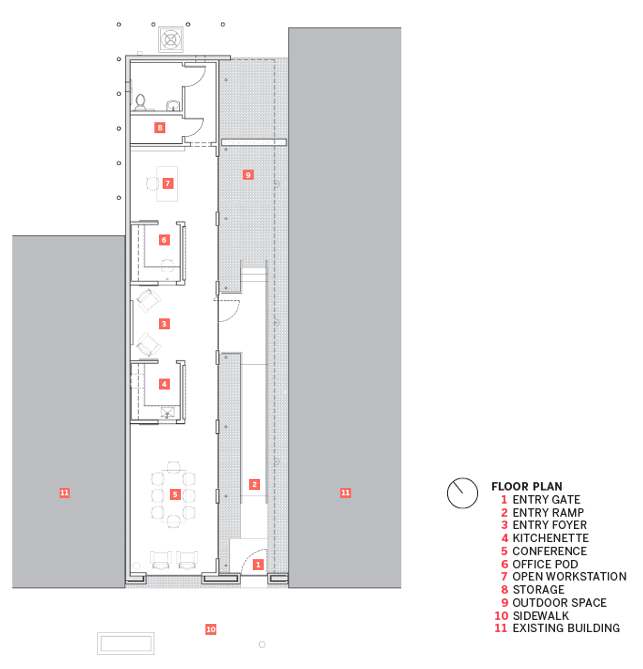

But this is the signature design move of the small, elegant project, setting up how it is organized and experienced. Instead of entering the building straight from the front, one enters through an exquisitely detailed offset gate, or Japanese yakuimon. This gate, along with a large window, is set in a simple, south-facing limestone facade. After passing through the gate, one enters the long sheltered courtyard. Street noises and harsh sunlight quickly fade away.

On the left, all interior spaces are revealed by floor-to-ceiling windows facing the rubble limestone wall of the Talley Building next door. The wall, which has been cleaned and repointed, acts as an exterior focal point and acoustic sound treatment. The roof overhang of the long engawa does not quite touch this wall, and natural light spills down the rough face from the gap above, creating drama on what otherwise would have been a dark surface. When it rains, custom rain chains with unique splash guards prevent water from splashing on the exposed stone. Arriving at the back, one finds a modest side entry into a small foyer with a project gallery.

Throughout the interior, all details have been well tended to. Fronting the street is an open conference room, followed by two intimate workspaces designed for privacy and focused work. Wood accent walls defining these box-like workspaces feature a shou sugi ban, or charred, satin finish, creating warmth and depth. During my visit, several pedestrians were tempted to peer inside.

Interior materials are simple: natural wood, exposed steel, and CMU. Stitched leather accents and polished concrete complete the palette. Toward the back is a small restroom that could have been a simple back-of-house space, and no one would have been the wiser. Instead it features a small square window high on a wall providing a framed eye-level view of the historic Glen Rose water tower nearby—a built-in piece of art in a space that needs nothing else. That’s the organizing theme of the design—compression and decompression of space, looking inward and then looking out.

With a Stetson hat propped on his modest desk, Garnett is a quintessential native Texan, friendly and warm in person, and he cares deeply about building a residential design practice that resonates with the historic culture of Glen Rose and Texas. While Texans have a reputation for being boastful and loud about our state, when it comes to our courthouse squares, we quietly revere these unique places and shared history. Texas architects like Garnett continue to work in modest and creative ways to help preserve this legacy.

Lee Hill, AIA, is an artist and architect and works as a project director at VLK Architects in Fort Worth.

Also from this issue

The Home Office Reimagined: Spaces to Think, Reflect, Work, Dream, and Wonder

Oscar Riera Ojeda and James Moore McCown

Rizzoli, 2024