Homework

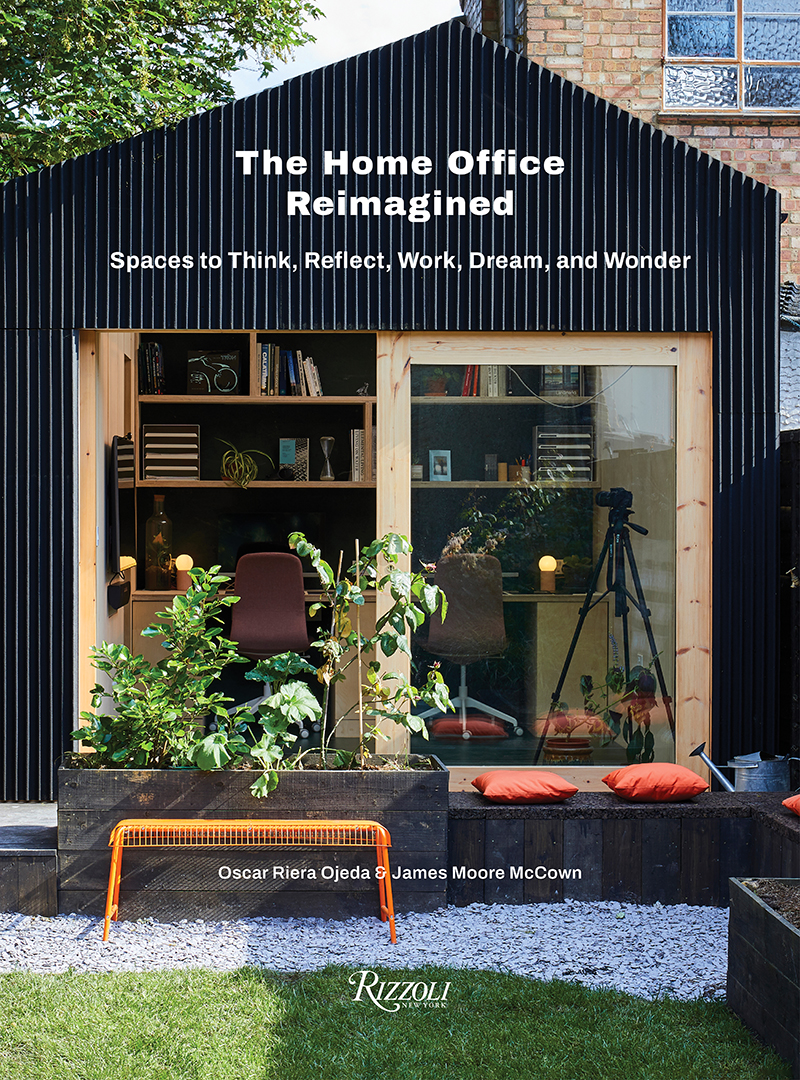

The Home Office Reimagined: Spaces to Think, Reflect, Work, Dream, and Wonder

Oscar Riera Ojeda and James Moore McCown

Rizzoli, 2024

When office workers became home office workers in 2020 following the COVID-19 pandemic closures, home offices became more than a weekend and evening necessity, if they existed at all. In addition to these, families added other spaces, like virtual meeting rooms, classrooms, and gyms.

Four years later, an estimated quarter of the workforce permanently works from home—a 10 percent increase—joining long-time remote or hybrid workers like me who had already integrated home offices into our lives. Those early believers include the owners of the 25 international home offices highlighted in The Home Office Reimagined: Spaces to Think, Reflect, Work, Dream, and Wonder, by publisherOscar Riera Ojeda and architecture journalist James Moore McCown.

The book shows the home office’s evolution throughout the past 20 years and explores how architects are confronting aspects of our new reality, including increased isolationism (both politically and publicly, in the case of the pandemic), the rising cost of materials, and the impacts of climate change.

As the authors point out, working from home is not new—it’s been around since medieval times. But with the Industrial Revolution came headquarters and other centralized offices that transformed workspaces, cultural life, and skyscapes. (It should be noted that onelarge demographic still worked from home during that time: stay-at-home moms.)

Yet the home office for paid workers already existed in the form of studios, libraries, and reading nooks for the privileged. A recent Wall Street Journal article describes how architects and designers are rethinking how to design for health, space, livelihood, and comfort, and this book shows that architects have, unsurprisingly, been doing that for decades.

All the featured projects share a few components. They’re separate from the main residences, emphasize light, and for the most part, are minimalist, allowing the owners to fill their space with what they want and providing flexibility for different kinds of work. The book’s global scope also reveals new narratives and forms specific to each location. In London, which is overrepresented in the book but provides enough projects to sense trends, the theme is playful and innovative, illustrating how eccentric ideas can work in small spaces and historic homes.

RISE Design Studio’s Brexit Bunker from 2019 is a real bunker. You get a sense the clients are not doomsday preppers but instead want shelter from the city. Its distinct feature is the hot-rolled steel cladding—the same material used on the nearby railroad—topped off with a pyramidal roof and an oriel window. The steel serves another purpose: allowing it to rust and chip away over time perhaps signals that everything in this world has a shelf life.

The wood, plywood, and steel Shoffice (from “shed” and “office”), or as I call it, the “Showoff office,” by Platform 5 Architects, occupies the backyard of a 1950s home. Its elliptical shell curls over itself and winds back down to create a terrace on the lawn. Settled under the shell is an oak-lined office outfitted with only a desk and storage space, a light above, and a window onto the terrace. What could otherwise be a fussy space is complemented by the sparse interior, which softens the loud exterior.

Studio Ben Allen’s A Room in the Garden is, as the architects call it, “a product and building.” It is influenced by the eccentric British architect John Nash’s 19th-century Royal Pavilion, with its quixotic mix of English and Indian influence. While nowhere near the size of that estate, it freely adapts from its most fun elements. The building is paneled with various shades of green and octagonal in form, and is capped by a hexagonal roof. Unlike the Royal Pavilion, however, it is spare inside, making it a great example of the marriage of past and present.

In humid São Paulo, two architects confronted the challenge of limited space for construction. To address the inability to build outward for a client, LCAC Arquitetura instead built upward in 2021 for a movie director’s workshop called Oficina Vila Madalena. The toolshed, which was constructed on the existing roof with views of the city, is minimalist, with a “pure Bauhaus” influence. It features a stunning view of the skyline and a rich courtyard below. The plain office has floor-to-ceiling windows and a simple interior with the drywall wrapped externally in cement boards to lessen the wear and tear from a subtropical climate.

In 2012–13, Brazilian architect Teresa Mascaro’s Studio 4×4 designed and built a photographer’s studio on a hill near the main house on the edge of São Paulo. The only available location for the project was on a slope filled with greenery. Another issue was the fact the client’s work is sensitive to light. In order to respect the land and not disrupt the soil, the firm took a non-invasive approach. The design employed sustainable materials and a steel frame solution, which “was adopted because it is easy to assemble and also due to its strength, agility and slenderness,” according to Mascaro. The box structure is level with the tops of the trees and clad with glass and opaque materials.

The handful of offices designed post-2020 in the book can be counted on one hand, making it difficult to find emerging trends.

Perhaps the best example is Boano Prišmontas’ modular My Room in the Garden. It addresses what otherwise is absent in the book: cost and a design for future mass migration. Their basic model is priced around $6,000, with expansions costing more. As we continue to grapple with global unrest, inflation, and scarcity and climate change forcing people from their homes, the concept proposed by the firm could serve as a prototype, especially as it is supposedly easy to assemble and expand upon. The firm isn’t new to rethinking the home office; Boano Prišmontas has researched and designed home offices during key periods of global challenge. Its Minima Moralia was designed in 2016, the same year as the Brexit referendum, and The Arches Project was completed in 2019, a year before remote work transformed the industrial world.

Gluck+, known for the Floating Box House in Austin, built a simple two-story cube for a scholar in Upstate New York in 2003. Elegant and conservative, it’s a habitat providing a quiet space to think and views of the surrounding forest. The first floor is a basement with no windows and only bookshelves, and the second floor is wrapped in windows and topped by a floating cantilevered roof. The authors describe the building’s purpose as programmatic and metaphorical, noting that “its alignment of use, structure, context and social effect comes close to the ever-elusive perfect diagram that artists are always seeking.”

In 2008, Erin Moore designed the Watershed for her mother, a professor of philosophy and noted nature writer. Moore, who is also a professor at the University of Oregon and runs the firm FLOAT Architecture Research and Design, is well known for working at the intersection of design and ecology, as illustrated by her design for the approximately 100-sf office. Mounted on concrete slabs, the writing studio sits on wetlands as part of a project restoring hydrological and ecological function to the nearby watershed. The emphasis on the environment includes incorporating the sound of falling rain, providing space for small species to crawl under and around the structure, and, eventually, allowing the structure to be torn down and recycled after it ceases to be useful. Like the Brexit Bunker, it’s a startling reminder of humanity’s vulnerabilities. But for now, we thankfully have a gorgeous book showing the ongoing promise and bold experimentation in home office architecture.

James Russell is a journalist in Fort Worth writing about art, the built environment, and politics. His writing has appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine, CityLab, Arts and Culture Texas, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, among others.

James Russell is a journalist in Fort Worth writing about art, the built environment, and politics. His writing has appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine, CityLab, Arts and Culture Texas, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, among others.

Also from this issue