Get Back

Project Row Houses preserves Houston’s historic Eldorado Ballroom for future generations.

Before Anita Webber Smith left Houston for college at Texas Tech University, she was an Army brat whose family lived in a three-bedroom ranch-style house on Rosedale Street in the heart of Third Ward. She attended Turner Elementary (now shuttered) down the street and recalled nights when her mother dressed up in beautiful dresses with pumps to go dancing with her aunt and uncle at the Eldorado Ballroom, located at the historic crossroads of Elgin Street and Emancipation Avenue (formerly Dowling Street), just minutes from downtown.

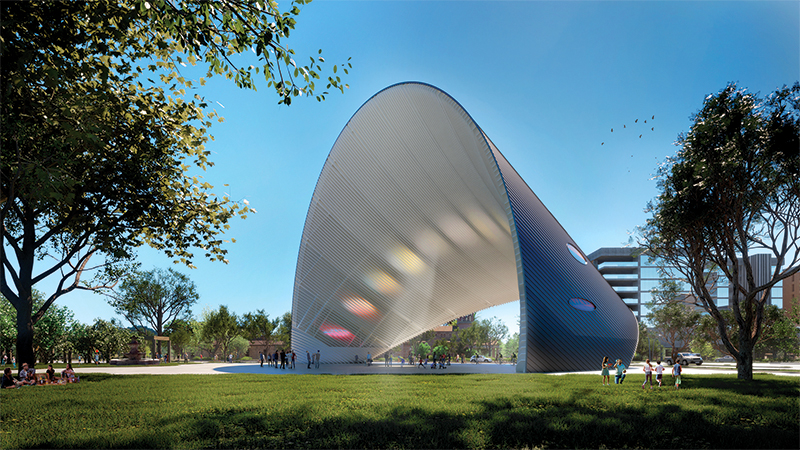

The building fronts Emancipation Park, a 10-acre city park dating back to the time of Reverend Jack Yates, a minister and founder of Freedmen’s Town (now Houston’s Fourth Ward). Until the 1950s, it was the only public park and swimming pool in Houston open to African Americans, and, later, civil rights rallies packed the green space.

While Smith was too young to go to Eldorado — she stayed home with her brother and the babysitter — those childhood memories growing up in Third Ward fueled her community work with Project Row Houses (PRH) to resurrect the ballroom where music legends like B.B. King, Ella Fitzgerald, James Brown, Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, and Jewel Brown (who sang with Louis Armstrong) once performed.

Project Row Houses is a nonprofit organization whose model for art and social engagement includes five city blocks and 39 structures that offer culturally enriching programmatic initiatives and community development activities. Smith, along with Hasty Johnson and Chris Williams, co-chaired the fundraising efforts and joined forces with former PRH Board President Bert Brown III and a host of supporters like the Kinder Foundation, Houston Endowment, and Brown Foundation, as well as other foundations and private donors. “There were foundations who didn’t know the building existed,” says Smith, who now serves as the PRH vice president. “Houston is a diverse city, so it was great to get the word out and see the support and collaboration.”

More than a music venue, the Eldorado was a “white-tablecloth” social club established by husband and wife Clarence Dupree and Anna Johnson Dupree in 1939 to provide prominent Black professionals and residents a place to belong, to enjoy live music, to host social events, and to celebrate milestones without discrimination during the Jim Crow era. To design the building, the Duprees hired Lenard Gabert Sr., who in 1917 was among the first to graduate from Rice with a B.S. in architecture and would go on to complete the Temple Emanu El in Houston with MacKie & Kamrath in 1949.

“The Eldorado was a finishing school for local talent with the house bands,” explains Roger Wood, historian and author of the book “Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues.” “What makes the Eldorado significantly different than other venues is that it was created as a community focal point.”

The ballroom was a launcher of music careers across numerous genres — blues, jazz, R&B, pop, and zydeco — and was an anchor of what was once the epicenter of life for African Americans in the city — a neighborhood that included churches, restaurants, offices, barber shops, a pharmacy, a movie theater, and the nearby Negro Hospital/Riverside General.

By the 1970s, desegregation, suburban mobility, private car ownership, and parking codes had changed the neighborhood, and the nightclub was closed. The building continued to be used for events by the community, including Texas Southern University fraternities and sororities, but was eventually shuttered. Hubert “Hub” Finkelstein, a white Jewish oilman who founded Medallion Oil Company, bought the property in 1984, saving it from demolition.

Finkelstein had grown up in nearby Riverside Terrace, where Jewish families owned mansions along the banks of Brays Bayou, a major tributary of Buffalo Bayou. Architects of Riverside Terrace residences included John F. Staub, Birdsall P. Briscoe, William Ward Watkin, Lenard Gabert, Joseph Finger, and John S. Chase Jr.

From the 1930s to the post-war era, the neighborhood was unofficially known as the “Jewish River Oaks,” and its demographics started shifting in the 1950s when Black professionals with families were attracted to the area’s proximity to downtown and Texas Southern University, the University of Houston, and the Medical Center.

Wood said Finkelstein used to stroll along Dowling Street, now Emancipation Avenue, where Juneteenth celebrations emanated from the park and where live jazz music wafted from the Eldorado’s open ribbon windows. That soulful music and the human spirit it represented undoubtedly imprinted upon him, as he grew up to become a prominent philanthropist supporting various Houston causes, including medical research at Baylor College of Medicine, The Methodist Hospital, the Asia Society, and Project Row Houses. He donated the ballroom property to PRH in 1999 before his death in 2001, as printed in his obituary in the Houston Chronicle.

It would take more than two decades, $10 million, and a reimagined plan to bring the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne ballroom back to its original grandeur, complete with its historic finishes, fixtures, and facades. David Bucek, FAIA, a principal at Stern and Bucek Architects, project manager Delaney Harris-Finch, and the rest of the design team led the architectural preservation efforts and worked with PRH, Forney Construction, and Hines, which lent their pro-bono project management services to the restoration efforts.

The building had survived two fires — one in 1941 and another in the early 1950s — and numerous patchwork projects over the decades. Stern and Bucek could not find any records of the original drawings, so as-built drawings had to be created. As they removed non-historic drywall and chipped back layers of paint to conduct historic forensics, the team also combed through newspaper photos and clippings, as well as private collections. They learned how the building evolved, uncovering anomalies and clues along the way: A 1939 drawing published in the paper revealed that there were more windows than they had surmised. Originally, there were ribbon windows on the east side. Could they be restored? Following the first fire, a damaged concrete beam at the east-end roof level was not replaced, but the concrete lintels elsewhere remained. After the second fire, modern air conditioning was installed, with large furr downs added for ductwork — resulting in removal of the near-full-height ribbon windows — and the roof structure had to be rebuilt with steel trusses. The first floor wood ceiling joists seemed to be original.

As layers of evidence were uncovered and peeled back, the building’s history began to come together to tell the narrative of bygone conditions. Just as the rings of a tree tell the stories of droughts and floods, the design team learned to interpret the ghosted wall lines and remnants left behind to determine the orders of the layers to make sense of the assemblies.

The plaster partitions of the new 5,000-sf ground floor, which includes an art gallery, meeting space, cafe, and mini-grocery, contrast yet harmonize with the deep hues of the stage and restored 4,000-sf wooden dance floor. A newly constructed addition to the south hosts service spaces, with a new dining room on the first floor and greenrooms on the second. It’s possible to trace the delicate outline of the original stage — which had been centered on the long axis of the space — where musical greats once stood, sang, and performed. The current stage is now centered along the short axis of the ballroom and provides access to a greenroom for the performers.

This rehabilitated project is a testament to reinvestment without displacement and a beacon of historic preservation, telling a story of societal significance and of firmly securing Black spaces instead of erasing them through development for profit. “The Eldorado is a place where history happened, and you can still go there and experience it,” says Bucek. “That’s the power of why to preserve and rehabilitate places for our culture.”

The Eldorado Ballroom received a 2023 Modernism in America Award from Docomomo US. It was one of seven projects to earn the Award of Excellence for best of modern preservation, documentation, and advocacy work. The US chapter is part of Docomomo International, a Netherlands-based nonprofit dedicated to the documentation and conservation of buildings, sites, and neighborhoods of the modern movements. Part of its mission is to act as a watchdog when important modern buildings anywhere are under threat, as well as elicit responsibility toward this architectural inheritance. Anita Webber Smith likened the restoration efforts to “a Jackson Pollock canvas with so many brush strokes near and dear to my heart.” She says, “It’s a victory to give back to the community.”

I interviewed Smith by phone for this article. As we closed the call, I thanked her for her time, and she also thanked me: “Thank you for your family business and investing in Third Ward, too.” For my refugee family, Third Ward was where my Vietnamese parents landed after a war, where I learned how to play the piano with Mrs. Audrey Whiting on Arbor Street, where I went to the library on Scott Street, and where my family had several small businesses: a corner store, a beauty salon, and a laundromat. Third Ward was our toehold for a life of freedom in America, too. Smith says, “I am thrilled to know Project Row Houses will keep the ballroom alive in Third Ward and [that it] won’t be victim to gentrification.”

Florence Tang, Assoc. AIA, NOMA, is a journalist, designer, and project manager based in Houston

Florence Tang, Assoc. AIA, NOMA, is a journalist, designer, and project manager based in Houston.

Also from this issue