A Crazy Feeling

WITH WINKING FORMAL ALLUSIONS AND WELL-TUNED SPACES, BUDDY HOLLY HALL PROMISES TO CONNECT LUBBOCK TO THE WORLD BEYOND THE LLANO ESTACADO.

Architect Diamond Schmitt

Architect of Record Parkhill

Associate Architect MWM Architects

Contractor Lee Lewis Construction

Structural Engineer Entuitive

MEP Engineer Crossey Engineering

Acoustics Jaffe Holden

Theater Planning Schuler Shook

Lighting Consullux Lighting Consultants

One summer night in 1970, two tornadoes cut a seven-mile swath from downtown Lubbock to the airport. While several large-scale civic projects emerged in their wake, much of the city’s growth migrated from its center to the fringe. The Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts and Sciences is the most notable investment in culture and the arts connecting the Hub City to national and international acts in 50 years, and it’s worthy of its namesake.

Located on the northern edge of downtown, Buddy Holly Hall provides a key component to the already robust Arts District in hopes of igniting a downtown resurgence in the form of future investments, all while increasing community engagement and opportunities for all ages.

At first glimpse from the highway, an unassuming banded gray facade wraps the boxlike form subtly rising above its low-slung surroundings. As one draws nearer, the two-toned, horizontally striated glass and metal envelope seems to echo the linear landscape of the Llano Estacado. The linearity is reinforced through the ribbon windows, which change from dark gray to bright white when the sun descends. This major mass becomes obscured at lower levels through an aggregation of several brick-clad volumes that are distinct from the banded core. The programmatic differentiation articulates the complexity within West Texas’ newest center for the performing arts while permitting entry and facilitating multiple activities through its seams.

A long, sloping entry volume extends beyond the box and southward toward downtown while formally gesturing east in a “bird’s tail,” a reminder of its connection to the arts district. As one approaches the main entry, towering vertical fiberglass fins set at various rotations shade the promenade and the all-glass facade. Here, verticality and lightness contrast nicely with the heavier tone of the somber brick and metal cubes. Where the fins stop, fritted glass is used to minimize heat gain.

Just past the single-story vestibule, white ribbons of stacked steel draw one’s eyes to the skylit space. The obvious highlight is a four-story helical stair, fabricated from 110 tons of steel. Inspired by the 1970 tornadoes, the winding stair offers minimal risers that radiate from the voided center. The terrazzo treads hover, allowing oblique glimpses through the open risers and curving glass railing as one transitions vertically. This visual permeability contrasts with the sturdiness of the massive structure. The sinuous white stripe spins effortlessly up four levels, connecting to the main theater space beyond and memorializing the tragic event.

A counterpoint to the soaring stair on the western end of the four-story entry lobby is the beautifully designed and meticulously crafted 30-ft-by-120-ft donor wall featuring an iconic image of Buddy Holly playing a Fender Stratocaster. Imagined by Diamond Schmitt and designed by Texas artist Brad Oldham, the pixelated mural is rendered with nearly 9,000 guitar picks of varying sizes and prominently displayed through the transparent southern facade.

One subtle yet attuned detail is the handrail, which is shaped in the profile of a pick. Crafted in wood and elegantly supported by tapering cruciform steel verticals, the handrail creates an illusion of both lightness and warmth that unifies the lobby, stair, and main performance space in a solid handshake with the building. Another deft and subtle touch is the richly colored Venetian plaster walls, which enliven the central lobby while further distinguishing the three performance volumes.

The primary performance space, the 2,297-seat Helen DeVitt Jones Theater, occupies the main volume and extends four levels in elevation. Wood finishes and light-colored cushions soften the seating area and steps, while an unpretentious use of steel flat bar turned horizontally creates a border for the balcony areas and maximizes views toward the stage. These two simple materials are juxtaposed throughout the project. A uniquely designed chandelier is suspended below a black ceiling plane, mimicking the large, star-filled sky typical of windswept West Texas nights.

The second, smaller performance space is the 415-seat Crickets Studio Theater, located at the building’s western edge. The theater offers a high-quality orchestra space for local middle- to high-school students, including a practice and performance area. Tilt-up concrete walls, measuring 53 ft high, are formed with acoustically determined horizontal waves on the interior that perform structurally and act as the finished surface. An orchestra shell can be deployed for a fuller, richer sound and to help the space achieve its NC-15 rating. This theater is quite a gift to the Lubbock community, as it provides a venue where children can perform and dream of becoming “the next Buddy Holly.”

Finally, the 6,000-sf Grand Hall flanks the eastern edge and offers a visual connection with the Arts District. The dividable, multipurpose space is tucked behind the guitar pick wall. Ventilated wood slats atop acoustic paneling clad the interior, and the space showcases large glass walls, which seem to extend the interior toward the bird’s tail courtyard beyond.

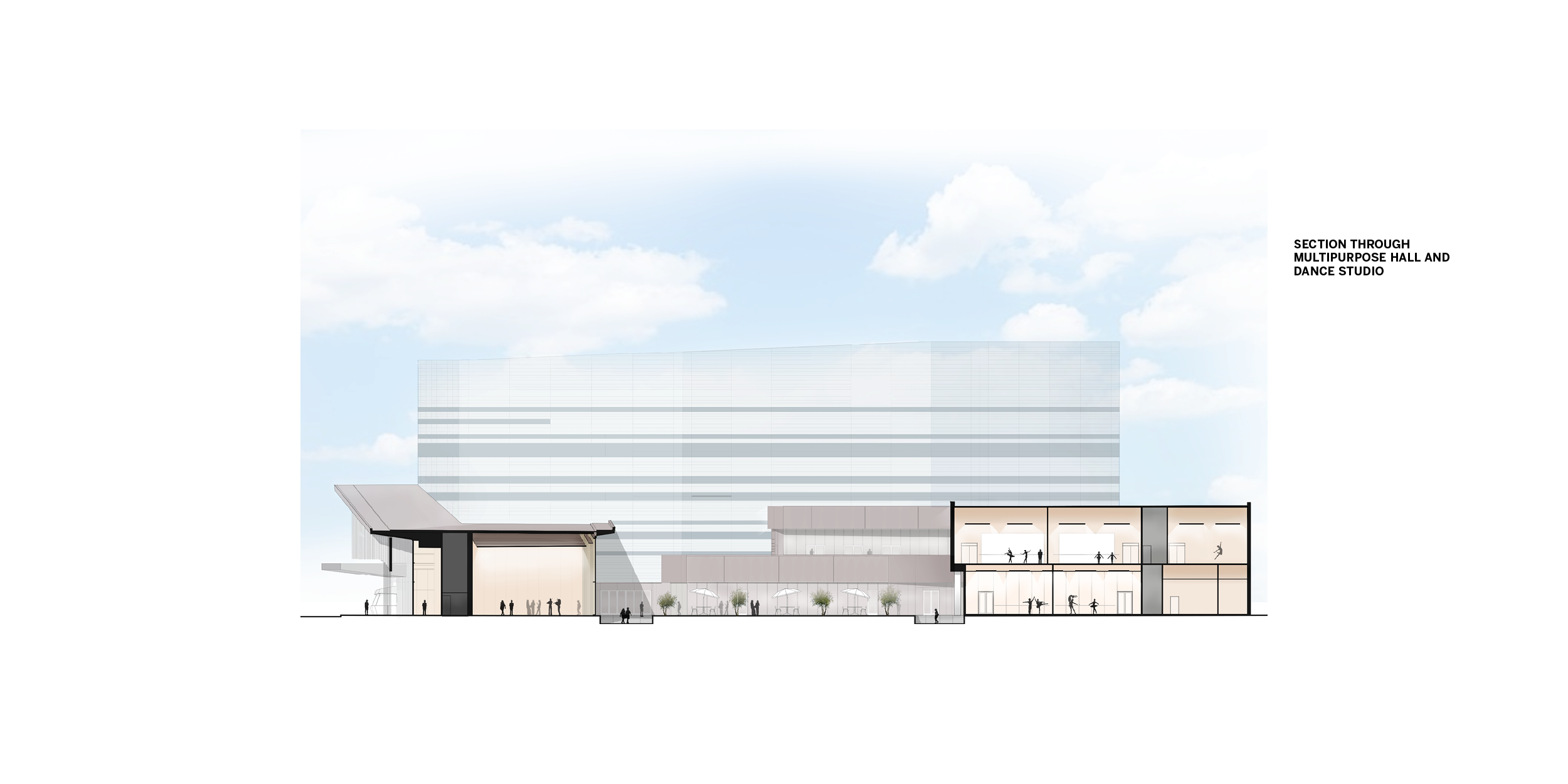

Two additional spaces make up the lower northeastern corner of the complex, supplementing the performance areas: the bistro restaurant, Rave On, and the 22,000-sf pre-professional school and offices of Ballet Lubbock. These spaces communicate through well-placed windows across a xeriscape of native cacti, grasses, and yucca. The two-story ballet area has a separate, private entrance, and offers a large rehearsal room, numerous offices, smaller practice spaces, a physical therapy room, and a digital interface for parents to watch their children practice. The space is designed for future expansion, though it currently almost triples the footprint of this treasured institution’s previous home.

With each space having its own back-of-house areas — loading docks, dressing rooms, and entries — the Hall could feasibly support three simultaneous events, in addition to Rave On and Ballet Lubbock, without interruption. This flexibility demonstrates the architectural team’s ability to tackle such complexities with dexterity and care. One such choreographic detail is a hidden, 20-ft-tall partition grille that slides out to separate the educational spaces from the larger theater space and restaurant, preventing alcohol sales to the underaged. This door is gracefully concealed within a Venetian plaster pocket and aligns with the vertical glass mullions of the southern entry when deployed. Another detail is the use of simple clerestory ribbons within the dressing areas. These admit soft northern light and a slice of sky into the dressing areas while gracefully blocking out the freeway just beyond view.

By way of critique, the Buddy Holly Hall project was over budget, did not open in January 2020 as anticipated, and has some underwhelming final touches. A close inspection reveals that several details are less precise than its $600/sf budget could have afforded, and the finishes and furniture of the restaurant fail to live up to the standard set by those of the main theater and lobby. This disappointment extends to the beverage/snack service carts deployed on the upper floors, which seem to be late additions, quickly conceived and constructed in rather lackluster white laminate.

All in all, however, this enormous investment in culture and the arts is worthy of its legendary name. Buddy Holly Hall promises the potential to connect Lubbock to the vastness beyond — it is a proper venue for performances by national and international acts and for community-focused programs that will help the ongoing rebuilding of a piece of city fabric flattened in 1970. Buddy Holly Hall is a much needed, unique performance center to guide and serve Lubbock’s bright future.

Peter Raab is an associate professor at the Texas Tech University College of Architecture.

Also from this issue