Architecture Seen

The professional photography of architecture has not changed fundamentally since dry sensitized photographic plates were introduced in the mid-19th century. Photographers could then travel the world and teach us what we know about architecture. They were interested in architecture and photography as a tool, and they understood the difference between a beautiful picture of a building and a building photographed beautifully. One is interpretive fine art and the application of personal style; the other is the avoidance of egocentric style in the search for design clarity, in which the photographer produces a beautiful social document, but hides his hand.

Digital technology has made all this easier and represents a seismic jolt in the evolution of photography. It has changed everything except that which is most important. What has not changed was perhaps best expressed by John Szarkowski, the former director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, who wrote that “the photographer is tied to the facts of things, and it is his problem to force the facts to tell the truth.” And since architecture, as opposed to building construction, is the most important fine art in the world and primarily a thing for the eyes, the truth is simply what photographers have shown us of the past, what we will see today, and what we will remember tomorrow.

We accept traditional architectural photography as truthful, but we must recognize the limitations of marketing photography commissioned by architects and other building professionals that typically results in buildings photographed as “products” sitting majestically alone without contextual or human reference. These pictures are effective in boardroom presentations or on the architect’s website, but less effective in the public arena, where beautiful photographs of those luxurious “things” often seem simplistic, perfectly pristine, perfectly staged, and too good to be true.

We should recognize that public awareness of the goals and the life-affirming promises of a better architecture is diminished, not only by the limitations of architectural photography, but by both the reluctance of our profession to commit time and treasure to public outreach programs and the lack of effective journalistic criticism of those who design, develop, and build. Architects and others, including photographers who work on the periphery of architectural practice, live with the frustration and the reluctant acceptance of the gap between architects and the public, described years ago by the legendary critic Ada Louise Huxtable. That gap still exists. The processes of architectural design are unknown to the public. To put it simply, people do not know what architects do. All architects want more freedom. One might ask: If the fascinating conceptual processes of design were more a part of the public’s knowledge, would it affect the conceptual processes of architectural design?

Photography has given us a world of architecture and proven that there are no rules, nor is there stylistic guidance, in either architecture or photography. Architects and their photographers need not change proven and effective presentation techniques, but perhaps there are alternative ways to photograph architecture that symbolize our visual experience within the chaotic complexity of cities.

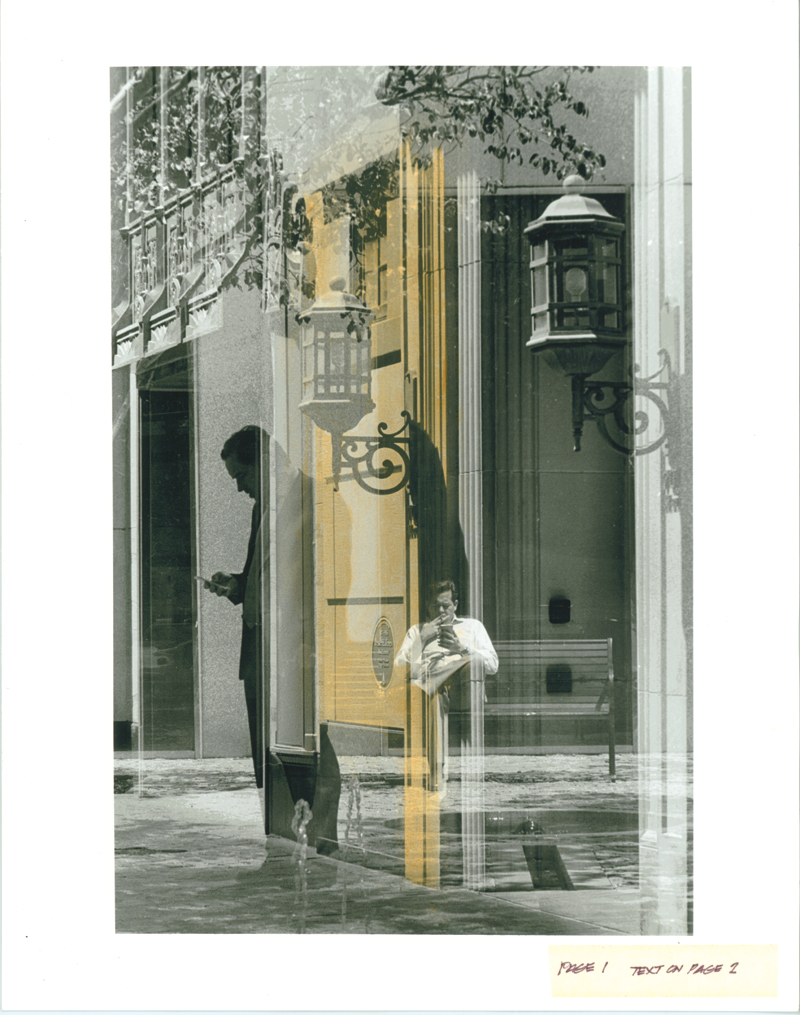

The photographs presented here employ interpretive methods common to the optimistic nature of all the arts. Multiple exposures are stacked, staggered, and layered. Color and darkroom techniques have been selectively applied in ways that are investigative, experimental, and provocative.

The photographs are about the mechanics of sight. They are not pictures of an instant, but of a span of time in multiple locations. They are impressions, urban imagery, pictures of memories, and symbols of what we know to be true of urban life. Emphasis is placed on producing images symbolic of how we see — not in a series of carefully composed, fixed images with edges or glances that start and stop, but rather in overlapping layers of ambiguous, continuous streams of imagery that flow through our eyes to our brains as we keep looking. What we see now will merge with what we will see, and what we have seen will be stored in memory. And since we cannot know what we will see in the next minute, I have made photographs over which I have had very little control.

Richard Payne, FAIA, is a former practicing architect and photographer in Houston.