Why we love the places we love

Lessons in Mass Timber

The Greenhill School campus in the Dallas suburb of Addison has a long association with architectural excellence. Spaces that could shape a learning experience by sparking awareness of place were a founding value for the campus with their selection of the late O’Neil Ford, FAIA, to design the initial buildings. Ford’s vision and work have been expanded on over the last five decades to include significant works by Lake|Flato Architects, Weiss/Manfredi, and now the storied firm of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, founded by AIA Gold Medal recipient Peter Bohlin, FAIA. BCJ completed most recent addition to the school, the new Rosa O. Valdes STEM + Innovation Center. The firm’s Philadelphia office was commissioned for the project due to its significant portfolio of education facilities.

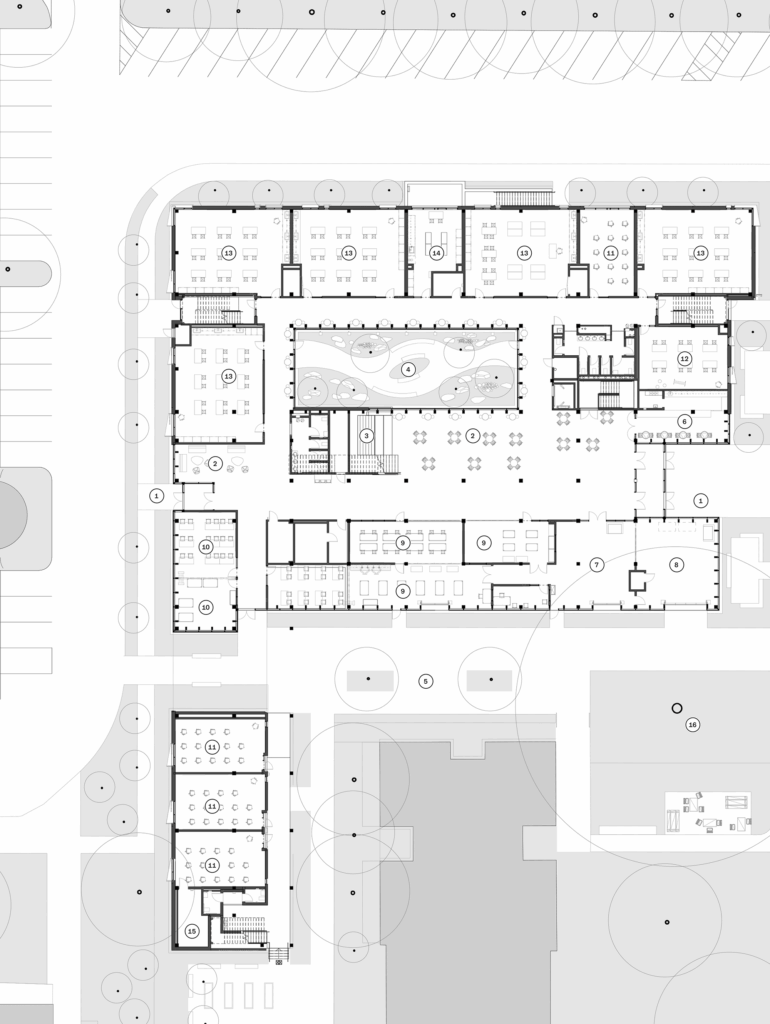

The Valdes Center was conceived by Greenhill as a STEM classroom and lab building that would set the standard for STEM education in the Dallas area. While Greenhill has always featured a rich combination of humanities and sciences in its curriculum, the growing focus on high-quality math and science education created a need for a facility to match the strong emphasis on these pedagogic offerings. The resulting 67,000-sf building was envisioned as a mix of math and science classrooms augmented with maker spaces, innovation labs, and computer labs. All these spaces would be organized in a way that allowed students views of the activities taking place inside them, as promoting curiosity about STEM subjects through exposure and access was a fundamental goal for the project.

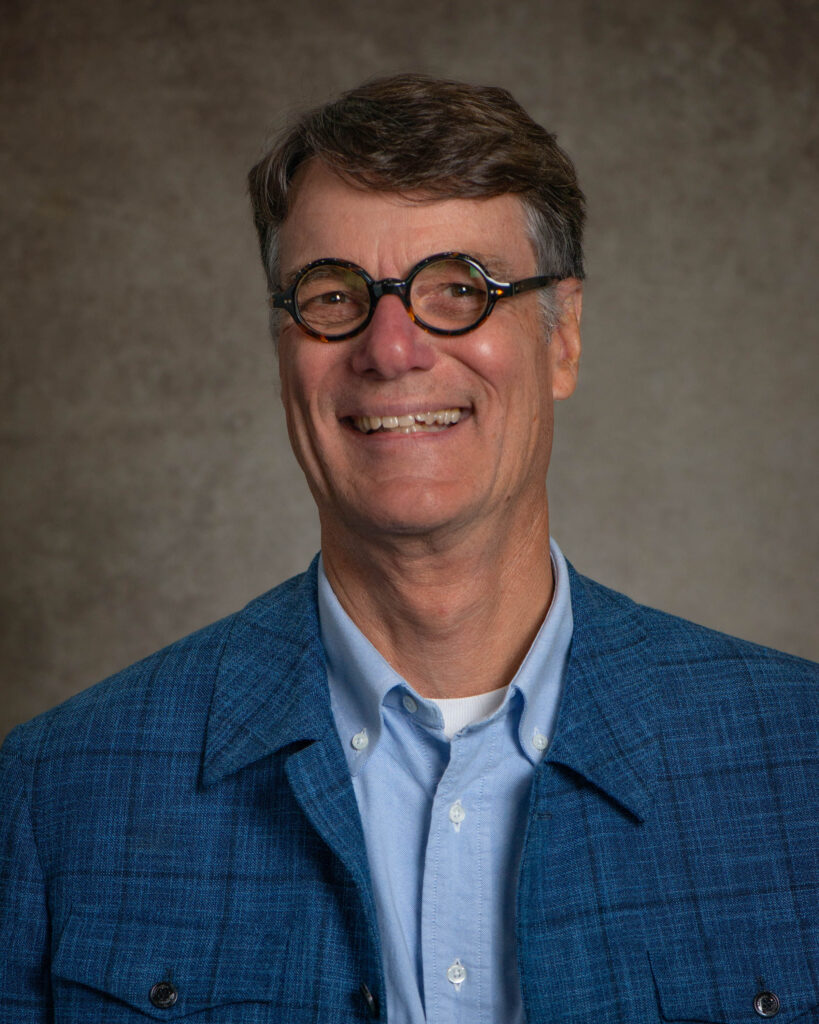

To ensure the building would be a worthy intervention on campus, work on the project was initiated with a vision statement, created jointly by Greenhill and the architects, that would act as a guide for design and documentation. “Greenhill wanted a new building that belonged to the campus—not to intentionally make a statement but to complement the existing fabric,” said Daniel Lee, AIA, the BCJ design principal on the project. What sets the buildings at Greenhill apart and best characterizes the work of the school’s previous architects is rigorous detailing and thoughtful integration of materials. This built heritage was communicated to BCJ on visits to the campus and through their own research, allowing them to understand and consider the opportunities to extend and explore new directions for the language.

The vision statement also included wide-ranging goals for social engagement, recognition for underrepresented groups, new architecture to match high standards of the existing campus, and flexibility in the use and organization of space. The team referred to the statement throughout the process to make sure the project was being mindful of these foundational goals.

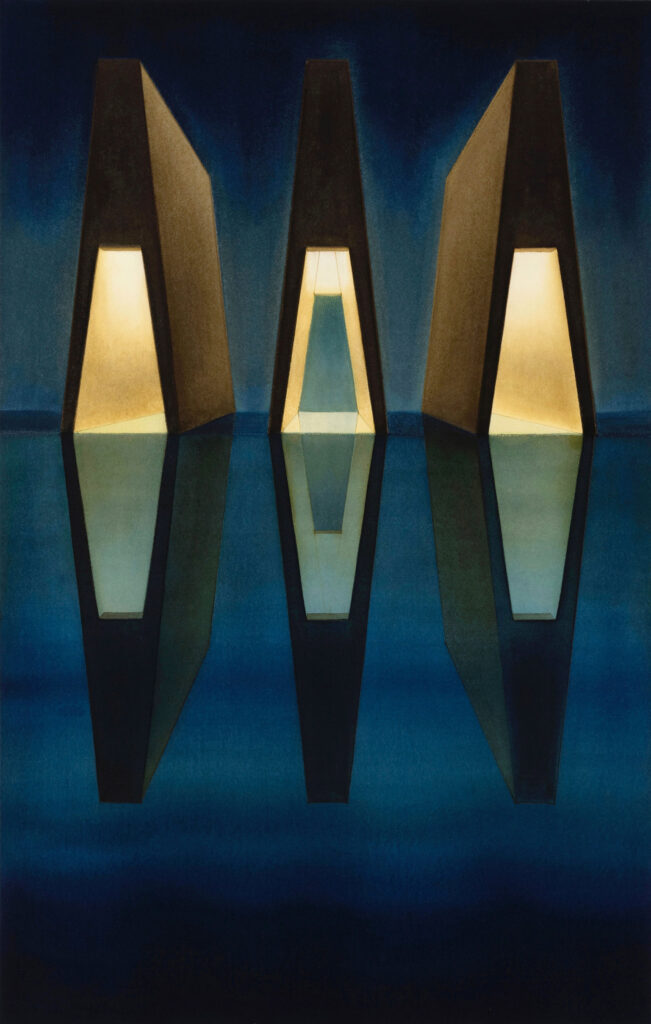

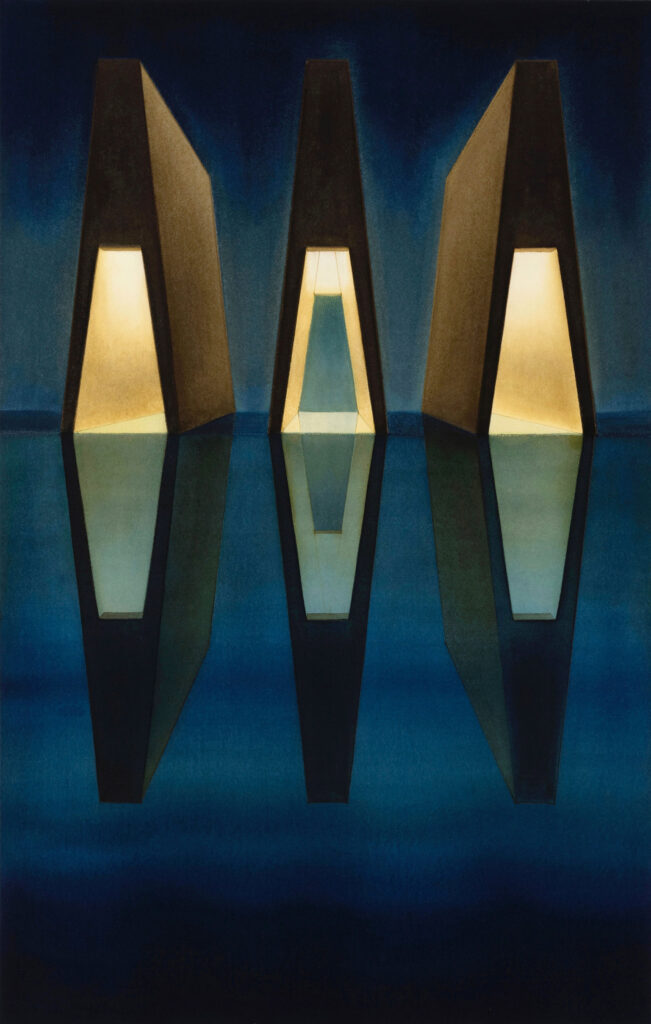

Once the core values were affirmed and the architects understood the architectural precedents in place on the campus, Greenhill put a lot of trust in BCJ and allowed them to drive the process, with remarkable results. When visiting the campus, one is struck by its casual, informal organization and humble materiality, something unexpected in an independent school with Greenhill’s reputation for academic excellence. For their structure, the buildings employ wood—often heavy timber—which is always expressed and integral to the organization of the various program elements. The spatial outlines defined by these structural frameworks are usually paired with masonry walls and, when appropriate, accentuate views or provide natural lighting through expansive glass panels.

The Valdes Center is the first mass timber building in Addison and one of the first in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Early in the design process Greenhill and BCJ made a commitment to sustainability that informed all the design decisions and material choices for the building. According to Margaret Sledge, AIA, NOMA, BCJ’s director of sustainability: “BCJ saw sustainability as a tool to be used in the process and to be expressed in the massing and details of the building. The design team and faculty embraced the idea of putting sustainable strategies on display so they could be understood and experienced by the students in real time.” BCJ investigated steel and concrete before settling on mass timber and cross laminate timber (CLT) as the right choice for the building’s structure. In addition to being a sustainable choice, wood had a contextual role on the campus as part of its architectural legacy. Once BCJ committed to the material, the design was organized to support the technology and play into the expression of structure as a primary design and visual element of the building. Douglas fir glulam is used for beams and columns, while the floors and roofs are CLT panels. The resulting loft-like spaces are open, entirely flexible, and allow for a variety of seating, lab bench, and computer configurations.

“The gathering ‘commons’ space was not provided for in the program, and it evolved with the design.”

BCJ’s best work has always dealt with structure as separate from enclosure, and the celebration of structural systems is replete in all of their most important projects. The post and beam nature of the wood framing is the primary definer of the Valdes Center’s spaces—and no place more so than the central gathering space with its social stair. This light filled atrium is enclosed by glass and topped with skylights. “The gathering ‘commons’ space was not provided for in the program, and it evolved with the design” says Lee. “Further, the space solved a number of circulation problems inherent in buildings with multiple spaces (think classrooms and lab spaces) that are repeated for various uses.” The atrium enabled BCJ to eschew double-loaded corridors for circulation. As completed, it is one of the most beautiful rooms in Dallas, and it is hard to imagine the project without it. The space provides a hangout space for students while accommodating vertical circulation and serves as a place for talks and presentations to large groups.

The adjacent interior courtyard is part of the daylighting strategy for the entire building. BCJ wanted to avoid having the building’s perimeter be taken up with circulation, so the courtyard became a way to organize flow and bring light into the core of the building. (The space evokes memories of the original science building, designed by Ford and demolished to make way for the Valdes Center—it too had a courtyard, which had unfortunately been infilled to provide additional instructional space.) With the incorporation of rainwater harvesting, the Valdes Center’s courtyard becomes a spatial and experiential ambassador, getting Greenhill’s lower school students excited about the STEM offerings. The courtyard serves as a rain garden, with the building’s roof drains feeding into a restored campus cistern. Demonstration green roofs with elaborate plantings are also strategically located where the building’s users can see and experience them.

Greenhill’s masonry heritage is explored by BCJ in the design of the facades that face onto existing exterior spaces and adjacent buildings. The exterior is primarily brick, when not glass, and part of the extensive daylighting strategy at play in the design. The brick takes on a variety of patterns and textures, providing a sense of being woven rather than of solidity and mass. In some places the masonry walls are pulled away from the building and become delicate perforated screens, shielding stairs and other circulation while allowing for light and breezes. Wood siding is also used on the exterior, as a tactile, warm material in places where students come into contact with it and where it can be protected by overhangs.

The Rosa O. Valdes STEM + Innovation Center is clearly related to Greenhill’s DNA but goes in directions that are new, fresh, and more overtly social than previous structures. This is a place that makes learning exciting and engagement with the material infectious. The building feels like it was created to encourage gathering and celebration—it is open and cheerful, completely alive during school hours. Designed with the intent to serve science and technology education, the Valdes Center also is an important reminder that the life around us can be enhanced and rewarded with the creation of thoughtful buildings that encourage and communicate the importance of our environment for our everyday lives.

Michael Malone, FAIA, is the founding principal of Malone Maxwell Dennehy Architects and an adjunct assistant professor of architecture at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Why we love the places we love

A Space Designed to Age Like Whiskey

Restoring a Midcentury Townhouse

Why Every City Needs an Architect

Learning from Biogenic Materials

The Allen Teleport 50 Years Later

Atlas of Never Built Architecture

Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024

City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways

Megan Kimble

Crown Publishing Group, 2024

The Brutalist

Directed by Brady Corbet

Written by Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold

Brookstreet Pictures and Kaplan Morrison, 2024

Each of these new products takes a novel approach to traditional surfacing materials—from recycled plastic to metal to concrete.