Why we love the places we love

Create state-of-the-art facilities or honor cultural heritage? This question is at the heart of a debate over the 10-year campus master plan for the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) presented by its president, Heather Wilson, to the UT System Board of Regents in August last year. As a practitioner, educator, director of the graduate program in Historic Preservation at Texas Tech, and an El Paso resident, the question is easy for me to answer: both can and should be achieved through adaptive reuse or rehabilitation, where character-defining features—either historical or architectural—are identified, preserved, and highlighted, while additions and changes—aesthetic, structural, functional, or spatial—bring the functionality of the building up to date.

The broad purpose of the new plan is to address aging infrastructure, improve research capabilities, and upgrade campus connectivity. However, the plan also calls for the demolition of multiple historic buildings and has, therefore, become a source of controversy within the UTEP community and among preservationists more generally. At issue are five to as many as nine of 21 original Bhutanese Revival buildings constructed between 1917 and 1951—buildings that both give the campus a distinctive historical and cultural appearance and speak to its modern agenda of embracing students across diverse communities.

From its founding in 1914 as the Texas State School of Mines and Metallurgy, UTEP has evolved into a major research institution known for serving the US-Mexico border region—one of the largest binational communities in the world. With approximately 84 percent of its 24,000 students identifying as Hispanic, UTEP is recognized as a leading Hispanic-serving institution. Further, more than half its students are first-generation college attendees, reflecting the university’s strong commitment to educational accessibility. Offering 170 degree programs at the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral levels, UTEP stands as the only open-access top-tier research university in the country. In local terms, the university has played a crucial role in shaping El Paso’s academic and cultural landscape, fostering cross-border collaboration and emphasizing its unique regional identity. In national terms, the university provides a model for educating populations of students whom higher education has only in the last few decades started to serve effectively.

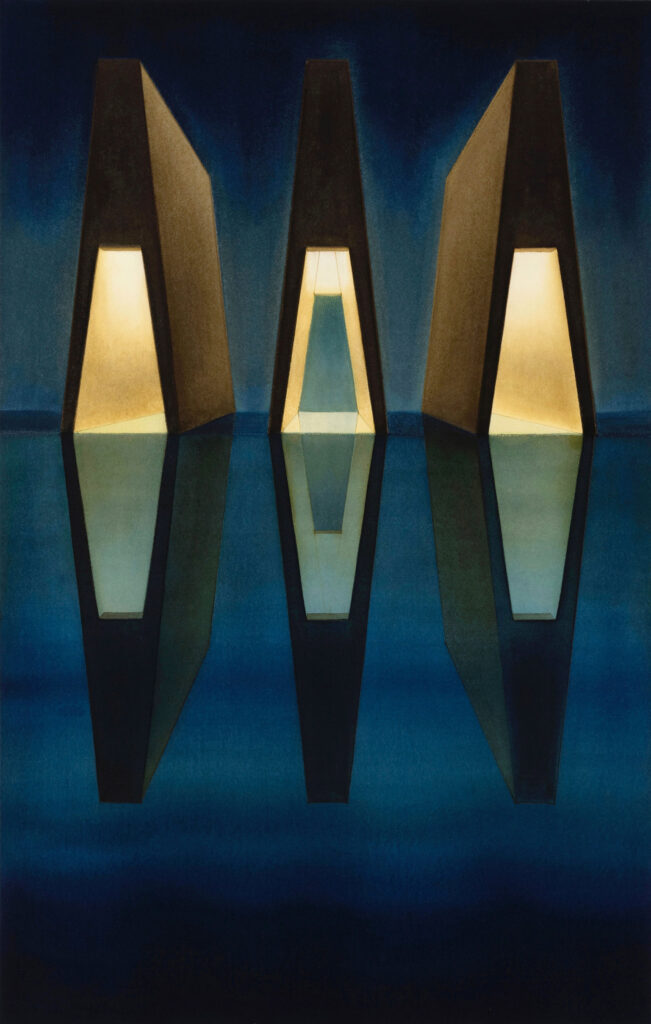

It is against this historical background and in this contemporary context that UTEP’s distinctive Bhutanese Revival architecture should be understood. Deeply rooted in Buddhist traditions and craftsmanship, Bhutanese architecture harmonizes with its natural surroundings through whitewashed rammed earth or stone walls, intricately carved wooden elements, and tiered roofs with golden finials. Characterized by massive sloping walls, high inset windows, and overhanging roofs, the core heritage buildings at UTEP—as identified during UTEP’s 2014 centennial celebration—were inspired by the Kingdom of Bhutan’s traditional fortresses (“dzongs”), imposing structures designed to serve religious, administrative, and military functions. Their intricately carved windows and tiered roofs enhance their grandeur, while their integration with the landscape underscores Bhutan’s architectural philosophy.

The first structure in this style was introduced to UTEP in 1917, after a devastating fire had destroyed the original campus buildings. Captivated by images of Bhutanese buildings in a 1914 National Geographic article, it was Kathleen Worrell, wife of the school’s first dean, Steve H. Worrell, who suggested rebuilding in the style. Henry Trost (1860–1933)—a genius in adapting distinctive architectural styles, whether Chicago School, Art Deco, or Mission Revival, to the El Paso region—was selected to bring the vision to life. He, in fact, created a campus aesthetic that has become synonymous with UTEP’s identity. And, in 1933, the El Paso Times paid tribute to Trost, describing him as “[having] made a valid and lasting contribution to the development of this region,” partly on the strength of his Bhutanese-style work on the campus.

At the time of building, there was no relationship between the Chihuahuan Desert and the Kingdom of Bhutan. Yet, then as now, the buildings tie the campus and the local area to the Bhutanese tradition—and by extension to a larger world view—by responding to the environmental conditions of the region and playing a role in shaping its cultural conditions. The buildings are undeniably representative of and integral to UTEP’s identity and history in the region.

Whereas critics of the plan argue that the buildings represent a century-old connection between UTEP and the Kingdom of Bhutan, supporters emphasize the need to modernize campus facilities to better serve the current student population and support future growth. Of course, from an architectural point of view, there is no conflict between modernizing the campus and preserving its cultural context. Yet, it is still the case that the perceived tension between preserving historical architecture and pursuing modernization is a common challenge faced by institutions worldwide. For UTEP, the Bhutanese Revival buildings are more than just structures; they are embodiments of the university’s identity and its longstanding relationship with Bhutan. More generally, however, the potential loss of these buildings raises questions about how to honor and maintain cultural heritage while accommodating the evolving needs of university and local communities.

After concerns arose regarding potential large-scale demolition as part of UTEP’s 2024 Campus Master Plan, vice president for marketing and communication Lucas Roebuck stated in a phone interview with KFOX that these worries stemmed from a misinterpretation, asserting that no such demolitions were planned. Despite this assertion, the extent of any planned demolitions remains unclear, and efforts by the author to obtain further clarification from UTEP officials and local architects have been unsuccessful.

The university has stated that President Wilson will ultimately decide the fate of campus buildings, and while the community and the local government (the El Paso County Commissioners Court) are watching the situation closely, it may already be too late to save the 1949 Student Union Building. As one of the core heritage sites of UTEP, the Union Building constitutes a mid-century interpretation of Bhutanese architecture. It features distinctive indoor and outdoor spatial qualities, including a stepped courtyard seamlessly integrated with a bridge connection, that link the building’s east and west nuclei and create an outdoor hub in the center of campus. Yet, in a September 2024 referendum, UTEP students voted to replace Union West and renovate Union East.

It is possible that students who voted for demolition favored a modern facility without fully recognizing the building’s historical significance. Feedback from focus groups and town hall meetings indicated a desire for a modern, multipurpose building that could showcase UTEP pride and offer greater functionality with study and collaborative spaces paired with modern dining halls and recreational areas. The desired functions can be achieved through a sensitive rehabilitation of the entire existing structure—a plan that would involve updating the building yet preserving its significant architectural and historical character. With various federal and state-level tax incentives, rehabilitation has become a popular approach to simultaneously modernizing and safeguarding historic properties. In fact, El Paso boasts successful examples of such projects in its downtown, only a few miles away from UTEP’s Bhutanese Revival buildings. Many of these rehabilitation projects involved original designs by Henry Trost, including the Paso del Norte Hotel, the Plaza Hotel, the Bassett Tower (now the Aloft Hotel), and the Anson Mills Building.

Notably, around the world, exemplary rehabilitation projects have preserved the character of historic structures by introducing contrasting additions, thereby demonstrating a thoughtful balance between preservation and contemporary design. A striking example is the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where Daniel Libeskind’s bold, angular addition—known as the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal—creates a dynamic contrast with the original early 20th-century building while respecting its historic presence. Perhaps, then, though far from ideal, much can still be done to retain the overall character of the Union Building, even should the planned demolition proceed. That is, by following the principles of rehabilitation, we can still ensure harmony between the parts of the building that remain and any new addition.

As an R1 institution, UTEP is committed to providing state-of-the-art facilities to support the aspirations of its students and faculty. However, equally important is the university’s role as a community leader in preserving cultural heritage and promoting architecture and the arts more generally. Concerned about the potential demolition of historic campus buildings, Dr. P.J. Vierra, a UTEP historian and member of UTEP’s Heritage Commission, suggested that decisions may have been made hastily. In his view, as in mine, “ensuring transparency and historical awareness will be key to protecting the integrity of UTEP’s 1917–1951 campus.” Therefore, though modernizing facilities is essential, let us call for these historic buildings to be rehabilitated by blending contemporary needs with architectural heritage and so preserve the university’s unique character while bringing a new dynamism to its architectural contribution to the region, to our country, and even more broadly.

Mahyar Hadighi, PhD, is the director of the Historic Preservation and Design program at Texas Tech University.

Why we love the places we love

A Space Designed to Age Like Whiskey

Restoring a Midcentury Townhouse

Why Every City Needs an Architect

Lessons in Mass Timber

Learning from Biogenic Materials

The Allen Teleport 50 Years Later

Atlas of Never Built Architecture

Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024

City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways

Megan Kimble

Crown Publishing Group, 2024

The Brutalist

Directed by Brady Corbet

Written by Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold

Brookstreet Pictures and Kaplan Morrison, 2024

Each of these new products takes a novel approach to traditional surfacing materials—from recycled plastic to metal to concrete.