Why we love the places we love

Research for a book on the Mediterranean house drew me to Texas, and to the work of O’Neil Ford, FAIA, among others. It became immediately apparent that an indispensable source on O’Neil Ford’s architecture was Mary Carolyn George’s definitive monograph O’Neil Ford, Architect. After I read her text, her unique perspective on Ford piqued my interest in Texas houses. She and I had long conversations on a diverse range of cultural and artistic phenomena that became crucial to my understanding of Texas architecture. Much of what Mary Carolyn discussed paralleled phenomena that influenced the architecture of my home state of California, which she knew well: urban settlements by Spain, Mexican adobe construction, Western cowboys (I soon learned about her important work on the artist Mary Bonner’s prints of ranch life the 1920s), and many other topics.

Yet, most of our discussions centered on Texas modernism, especially as she interpreted it through Ford’s work. Her analysis echoed much of what I saw in the work of West Coast architects such as William W. Wurster, FAIA, and Harwell Hamilton Harris, FAIA, although my observations were hardly original. In the 1930s, architectural critic Talbot Hamlin noted a shared type of modernism in the domestic work of Ford and Wurster, arguing that each produced a form of “house design which is modern in its results because it is modern in its purposes, and not because its architecture had some fixed prejudice as to what was modern in style.” Mary Carolyn saw Wurster as one of Ford’s heroes, and eventually the architects collaborated on Trinity University in San Antonio. She argued that Ford, Wurster, Harris, and others shared a similar starting point—an interest in the vernacular architecture of their respective regions. They incorporated the idea of simplicity and a direct response to climate and landform into their architecture, all qualities that “read” as modern by the 1930s because of an avoidance of historicist ornament.

Fundamental to the success of Mary Carolyn’s book on Ford was her deep understanding, as a native and longtime resident of San Antonio, of the people he knew, the places he inhabited, and the structures and sites he designed. She gained comprehensive insight into Ford’s working methods thanks to numerous interviews with his clients and associated architects. In some cases, she met with both the client and the architects directly involved with each project, recognizing that reliance on a sole source would be an inadequate foundation for her analysis. Her broad-based, sweeping, and deeply embedded ground-up methodology was innovative and rarely used by others at the time. It was key to her success, allowing her to make connections and observe nuances of vision and meaning that might have been overlooked by others. For instance, Mary Carolyn was struck by the vitality of the young designers in Ford’s office, many of whom were graduates of the School of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin in the 1950s and early ’60s. Harwell Hamilton Harris was director of the school at the time (1951–1955) and hired the group of faculty later known as the “Texas Rangers.” To better understand and document the curriculum and teaching methods many members of Ford’s design staff experienced, Mary Carolyn prepared an unpublished paper entitled “Learning about Architecture: One Method that Worked.” She once again brought a unique perspective to the subject, having seen the impact of the faculty’s teaching methods and their curriculum on subsequent generations of Texas architects.

Mary Carolyn George’s passion for Texas history remained unwavering through the last years of her life.

Mary Carolyn was knowledgeable about architectural education; for 25 years she was an associate professor at San Antonio College, where she taught all the art and architectural history courses in the Department of Visual Arts and Technology. She also chaired the college’s Special Events Committee, which brought cutting edge films to the campus. Mary Carolyn’s own education consisted of a BA in art from Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia, and an MA in architectural history from the University of Texas at Austin. In addition to her teaching and writing, Mary Carolyn maintained a lifelong practice as a watercolor artist.

Mary Carolyn wrote her master’s thesis on the late-19th/early-20th century British architect Alfred Giles, who established a practice in San Antonio beginning in the 1870s and, around 1900 when Northern Mexico held more opportunities, opened an office in Monterrey. Soon after completion of her degree, her thesis was published as Alfred Giles: An English Architect in Texas and Mexico (1972) with the support of the San Antonio Conservation Society and the Steves family, whose antecedents commissioned Giles to design one of the city’s finest houses of the period. Mary Carolyn returned to the subject of Alfred Giles 34 years later with her book The Architectural Legacy of Alfred Giles: Selected Restorations (2006). The book presents the rehabilitation of many important Giles buildings, with only two having been demolished. One of the most spectacular “saves” she documents is the Daniel Sullivan Carriage House, a beautiful stable and coach house dating from 1896 that was relocated and reconstructed at the San Antonio Botanical Center, where it functions today as a restaurant.

Historic preservation was a serious pursuit of Mary Carolyn’s: she was a member of the San Antonio Conservation Society from 1977 to 2022, and in the late 1970s she was appointed to the Texas State Board of Review, the panel that recommends properties for the National Register of Historic Places. She met her second husband, Walter Eugene George, FAIA, at this time; he was also a member of the board. He was a preservation architect who is credited with reactivating the Historic American Building Survey program in Texas. The couple collaborated on several projects until the time of Gene’s death in 2013.

Mary Carolyn George’s passion for Texas history remained unwavering through the last years of her life. Her final book was Pearl Sets the Pace, which tells the story of San Antonio’s Koehler family, including their founding of the Pearl Brewery, their union with the Pace family, and the subsequent creation of Pace salsa. She carries the history through Linda Pace’s creation of Artpace and the Linda Pace Foundation (now housed in the Ruby City exhibition space designed by architect Sir David Adjaye, OM, OBE), as well as her former husband Kit Goldsbury’s funding of the award-winning Pearl Brewery Master Plan by Lake|Flato Architects and its realization as a vibrant mixed-use development in San Antonio.

Mary Carolyn passed on May 26, 2024. She is survived by her sons from her first marriage, Robert Michael Tempest Jutson Jr. and Scott Hollers Jutson (Sue), and by her two grandsons.

Mary Carolyn’s commitment to the built environment of Texas and San Antonio endured her entire professional life. She was a brilliant scholar who was motivated by a real need to constructively guide Texas’s architectural future by documenting and preserving its past. She leaves a huge lacuna in the field and will be missed, not least of all by me.

Lauren Weiss Bricker, PhD, is a professor emerita of architecture at California State Polytechnic University.

Why we love the places we love

A Space Designed to Age Like Whiskey

Restoring a Midcentury Townhouse

Why Every City Needs an Architect

Lessons in Mass Timber

Learning from Biogenic Materials

The Allen Teleport 50 Years Later

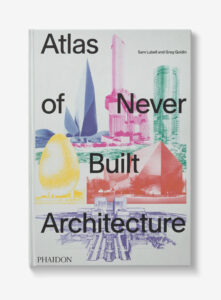

Atlas of Never Built Architecture

Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

Phaidon, 2024

City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways

Megan Kimble

Crown Publishing Group, 2024

The Brutalist

Directed by Brady Corbet

Written by Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold

Brookstreet Pictures and Kaplan Morrison, 2024

Each of these new products takes a novel approach to traditional surfacing materials—from recycled plastic to metal to concrete.