How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture

M+ Museum, Hong Kong

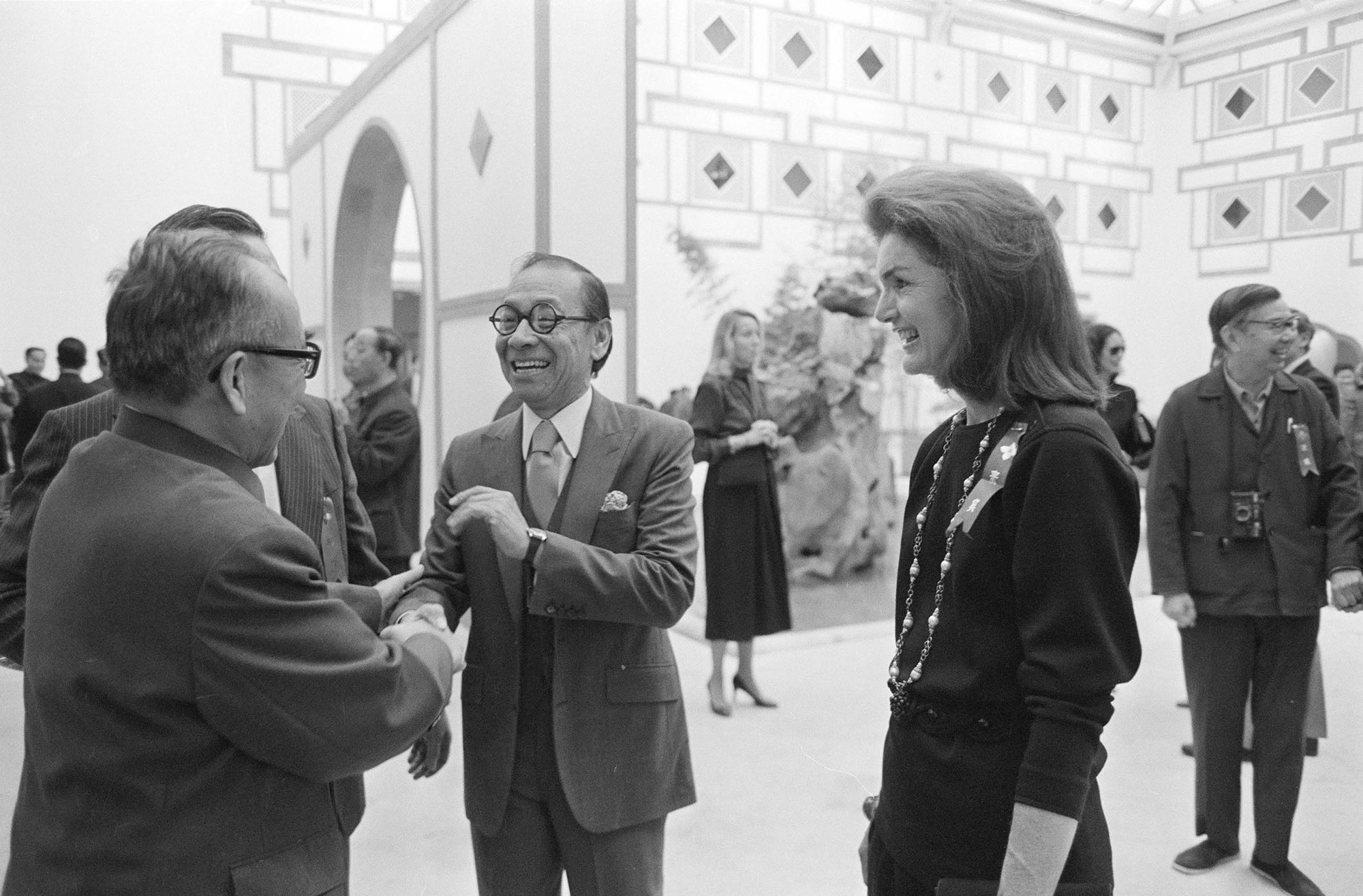

1963 was a bad year for Dallas. After JFK and Governor John Connally were shot on Elm Street, and the president’s assassin shot in the basement of city hall days later, new mayor Erik Jonsson needed to turn around the city’s hated image. He declared a raft of “Goals for Dallas,” including construction of a new city hall. When it came time to choose an architect for this landmark, what better olive branch than to select the rising star whom Jackie Kennedy had already picked to design Jack’s memorial library?

Such was I. M. Pei’s entrée into Texas, where he would go on to design eight buildings, mostly during the booming growth of Dallas and Houston in the ’70s and ’80s. Nevertheless, Pei’s Texas oeuvre forms a minor part of his overall legacy, at least as told by the retrospective recently on view at the M+ Museum in Hong Kong (completed by Herzog & de Meuron and Farrells in 2021 and itself worth a visit). This expansive exhibit traces Pei’s eight decades of practice through a rich variety of media, adding texture to a life some may know only from one or two museums.

For Pei superfans and casual museumgoers, the exhibit plays through the greatest hits: the architect’s winning persistence in the epic “battle of the Louvre,” his mingling with presidents and dignitaries, and his homecoming to China through the Fragrant Hill Hotel and the Suzhou Museum. For visitors that come cautious of Pei’s legacy—associated, however tenuously, with urban renewal, construction issues, formal rigidity, or undue focus on a solitary hero architect—there are challenges to any easy dismissal. In particular, Pei’s sensitivity to nature and culture were ahead of their time and are deserving of closer study by scholars and practitioners today.

The design of the exhibit is quasi-chronological, moving through six themes that begin with Pei’s formative years in China and Massachusetts. Here, the space is compressed and the walls are black, suggesting the mists of the past and the protean depths of origin. In the next theme, “Real Estate and Urban Development,” the walls are grey, coding his early work for developer William Zeckendorf as an incubation period. Then, after a knife-edged turn, the room erupts in light and space. The walls are bright white, and the remaining themes of art, patronage, innovation, and history wind around Pei’s pyramidal Louvre extension as a centerpiece. The borrowed views, triangular geometries, and crisp alignments of the exhibit are cues deftly taken from the architect’s own work. The message is that Pei—and you—have arrived.

Within the six themes, some projects repeat. Pei’s museum in Doha, Qatar, shows up under “Reinterpreting History through Design” and also under “Art and Civic Form.” Dallas City Hall first appears in “Power, Politics, and Patronage,” then again around the corner in “Material and Structural Innovation.” This repetition adds drag that a show this exhaustive should work to avoid, all the more because it is unnecessary. A host of projects are entirely absent from the exhibit, most conspicuously the Meyerson Symphony Center, Pei’s best-known Texas work. Projects like Meyerson or the Javits convention center in New York could have been included to eliminate duplicates and further capture the breadth of Pei’s incredible range of work, even if they are not his most lionized projects.

The repetition of projects is relieved by the cornucopia of media used to represent them. There are drop-dead gorgeous ink-on-vellum plans that will make any architect swoon. There are thumbnail sketches and construction details, historical models, newspaper clippings, and films. There are sculptures and paintings by artists with whom Pei collaborated. Most evocative are the scraps that bear traces of the man himself: a letter he wrote to his father while a student, an early sketch of the Luce Memorial Chapel, an index of historical precedents covered in annotations. While these, and a profile of the family retreat he designed in 1952, provide a small glimpse into his personal life, Pei’s intimate character remains elusive, subordinate to the public Pei of magazines, documentaries, and papers (there is a breakout section just on “Pei in the News”). Dazzled by his celebrity, I found myself eager for more of the small details of his life: what he was like to work with, how his desk looked, what he kept in his pockets.

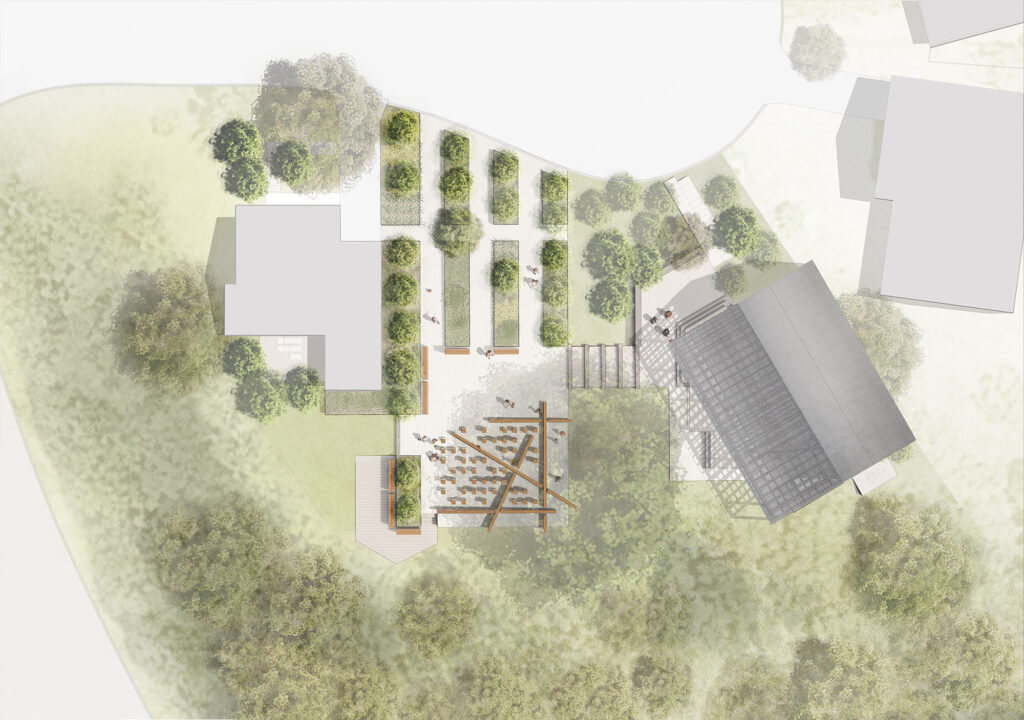

The exhibit commissioned new photographs of Pei’s buildings around the world and worked with Hong Kong architecture students to build large models, many of unbuilt projects. Pulling Pei’s legacy forward in this way was a curatorial masterstroke. The photographs connect the work to the present, igniting a conversation about permanence and change. Some of Pei’s projects have aged poorly or been demolished, while others—mostly museums—are as pristine as the day they opened, anchors of permanence in changing cities. The student models, in turn, project Pei into futures both hypothetical (what if Grand Central Station had been demolished and replaced by a hyperboloid skyscraper?) and imminent (what architecture will these students, touched by Pei, go on to create in their own careers?).

These photographs and models imbue the show with vitality, addressing the challenge posed to any retrospective: why should we care, now? Pei’s graduate thesis of nearly 80 years ago—an art museum for Shanghai—brought to life by two new models, would look at home in the portfolio of an up-and-coming Chinese firm today. Decades before the syntactical gymnastics of postmodernism, this thesis sought to find a design expression that was contemporary yet culturally specific. Even more electric is Pei’s undergraduate thesis at MIT, a prototypical communications pavilion, made of bamboo, to be deployed in villages across a chaotic wartime China. This project is thoroughly documented in the exhibit, with original drawings, the written thesis text, and two huge models by students at Hong Kong University. It reveals a young I. M. Pei alive to urgent social issues, deeply concerned with context, exploring alternative materials, and eager to push architecture beyond its own comfort zone. In other words, he is much like the architecture students I meet today.

This shock of recognition, of finding the new in the old, is both triumphant and disquieting. How triumphant to discover Pei’s prescience, his sensitivity to issues we often mistake as new, a vindication against critics who would dismiss Pei as too elite, too sterile, or too focused on form. Yet how disquieting to see time as a flat circle, to be reminded of the stubbornness of the world’s problems and the limitations of architecture to fix them. When today’s outstanding architecture students begin to receive prestigious commissions, will they be drawn away from the issues they wrestled with in school, to be absorbed by work on museums, office buildings, and private homes, leaving the world’s intractable problems to the next crop of wide-eyed adolescents? How disquieting to be reminded that, likely, they will.

It is in fully unfolding the complexity of Pei’s life, work, and legacy that “Life Is Architecture” reaps its greatest success. This is eloquently captured at the end of the show by Pei himself. After a whirlwind presentation of projects, decades, characters, and continents, there he is, projected onto a wall that is once again painted black, dressed as impeccably as always, sitting under a tree, and speaking directly to the camera: “You mean, [what’s it like] to see one’s own buildings? Mixed feelings!” Then you exit, the same way you came in.

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture will next tour to the Power Station of Art in Shanghai and Qatar Museums Gallery, Al Riwaq in Doha in 2025.

How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

An Ambitious Office Tower Redefines Urban Sustainability

Exploring the Perils and Delights of Houston’s Irreverent Approach to Urban Development

A Family’s Legacy of Excellence

How Can Utopic Ideals Be Engaged in Everyday Life?

Picture-Perfect Charm Along the Texas Gulf Coast

PS1200 Builds a Backdrop for Public Life

Exploring the Parallels Between Science Fiction and Architecture

Illuminated Wood Panels, Inserts for Brick Walls, and Fixtures Made from Recycled Plastic, Mycelium, and Hemp

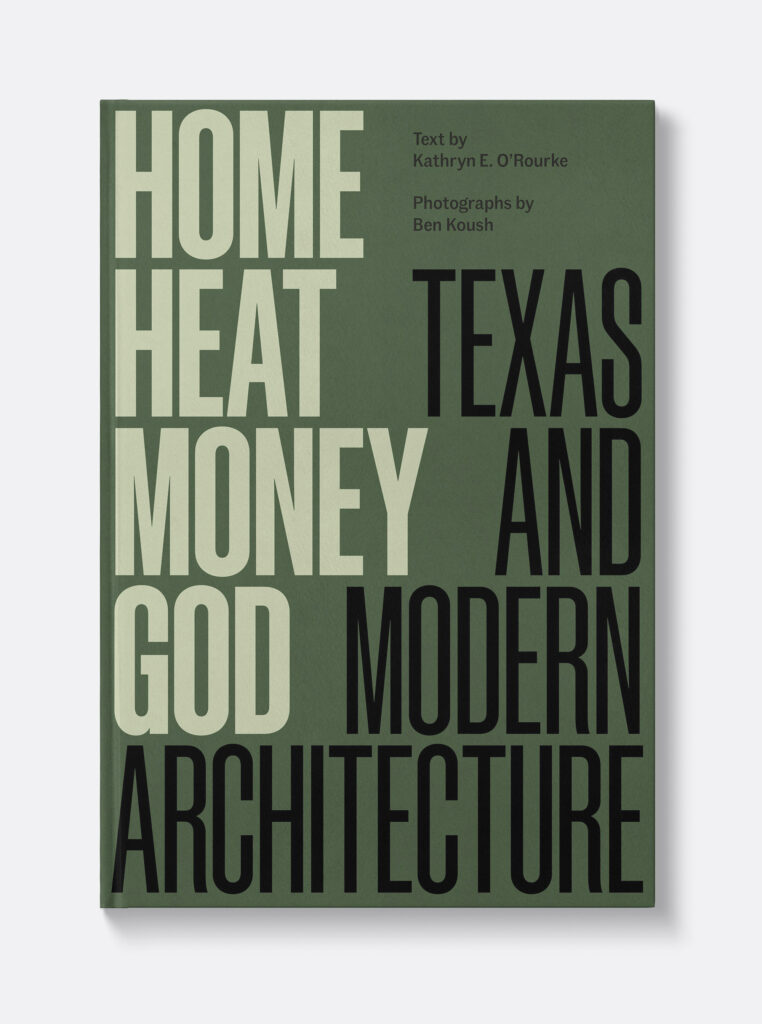

Home, Heat, Money, God: Texas and Modern Architecture

Text by Kathryn E. O’Rourke

Photographs by Ben Koush

University of Texas Press, 2024

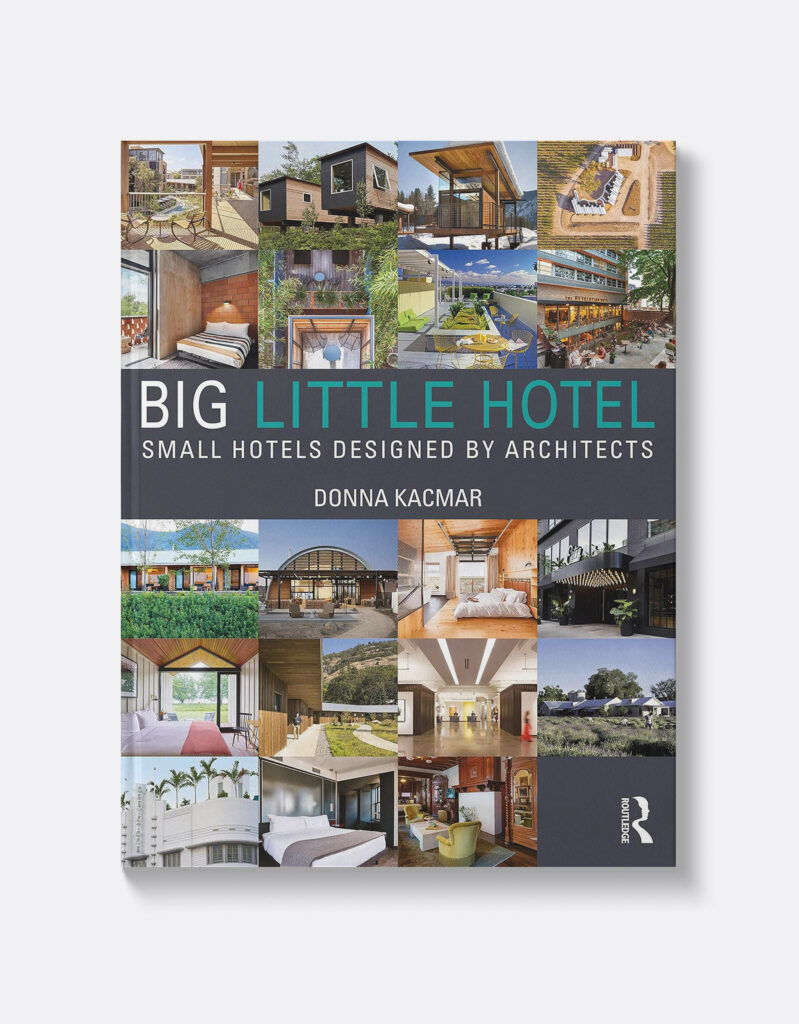

Big Little Hotel: Small Hotels Designed by Architects

Donna Kacmar, FAIA

Routledge, 2023