How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

Exploring the Perils and Delights of Houston’s Irreverent Approach to Urban Development

Sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic at the US 59 South and I-610 interchange feels like the furthest a Texan can get from utopia. In fact, many things about Houston seem to fly in the face of any ideal commonly held to be “utopian.” Concrete batch plants belch and smoke next door to subdivisions. When it rains, depressed freeways swell with water, and quaint drainage ditches do little to protect residents’ homes. The inner and outer loop draw concentric circles that suggest a sort of garden city sensibility, but this is only perceivable from satellites far above. On the ground, there is no such thing as the middle of Houston. Houston has tens of “middles.” It isn’t that Houstonians don’t dream of utopia, it’s just that we tend to do so in isolation.

Former Cite editor Jack Murphy has written that “Houston started as a utopian real estate scam.” Entrepreneurial brothers Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen bought the land that today makes up the city’s East End in 1837 for a little under $10,000. In 1850, there were only 2,396 Houstonians. Many of them had been lured to the swampy, humid settlement by grandiose advertisements that depicted Houston as a lush and civilized paradise. One such advertisement, put forth in the Telegraph and Texas Register in 1836, describes Houston as “handsome and beautifully elevated, salubrious and well watered” and declares that “there is no place in Texas more healthy, having an abundance of excellent spring water, and enjoying the sea breeze in all its freshness.”

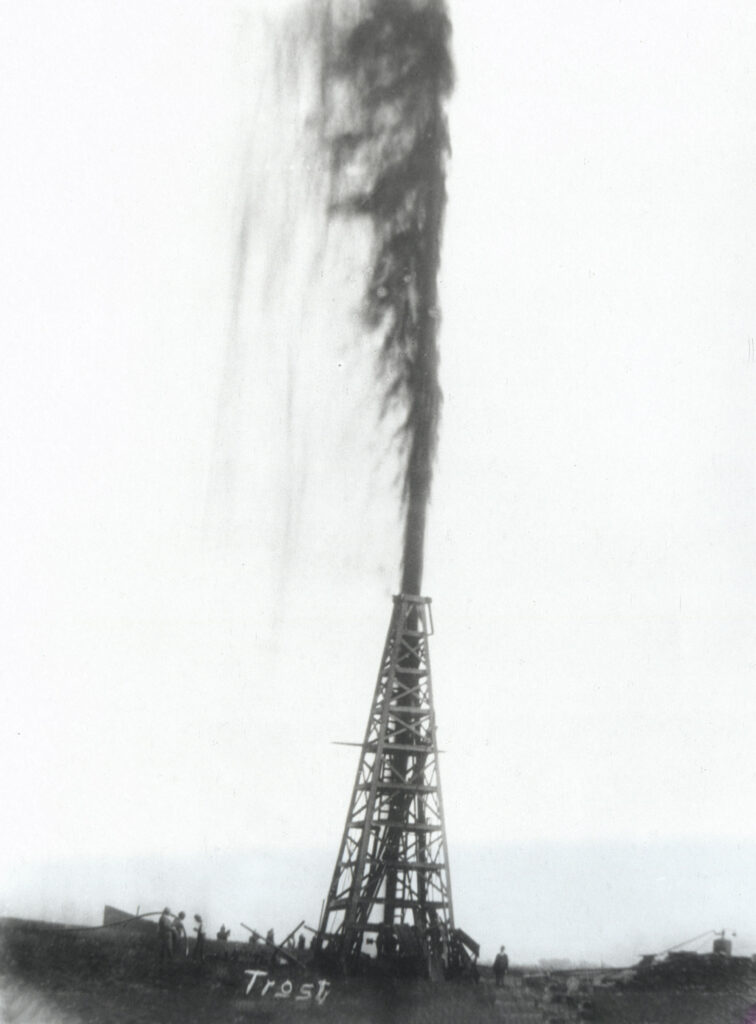

Despite the Allen brothers’ enthusiasm, it would take nearly a century for Houston to establish any sort of regional magnetism. When it did, it was not by way of its handsomeness or beauty, but rather the liquid gold below ground. In 1901, crude black oil gushed out of a well in Spindletop, just southeast of Houston. With Galveston still in ruins following the deadliest hurricane in United States history, Houston quickly became a critical nexus for the oil economy. Cultural institutions, public infrastructure, and industry rapidly proliferated. By the 1930s, Houston was the most populous city in Texas.

Yet, while New York City aligned development with the 1929 Regional Plan for New York and Its Environs and Chicago looked to Daniel Burnham’s 1909 comprehensive plan, Houston was already a city of developers by the time comprehensive planning came into vogue. Getting a planning commission off the ground and formalized proved a challenge in the first half of the 20th century. Zoning ordinances were proposed and rejected five times between 1929 and the 1990s, at which point they were infamously abandoned altogether.

A young city full of young money, awash in oil and growing in parallel with the prevalence of the automobile, Houston unrolled as a disjunctive patchwork of more or less realized desires. It’s unsurprising, then, that when celebrated critic Reyner Banham visited Houston in 1986, he described it as “an urbanist’s nightmare.” It seems paradoxical, though, that he also cited it as “the most Miesian city in North America [next to Chicago].” While Houston was establishing itself as a character of interest on the national—or at least Southwestern—stage, modernist ideology was being codified into an architectural style. Utopia as a timeless, placeless ideal undoubtedly anchored the exploits of modern architects. More than capturing an aesthetic quality, modern architects sought to create a new world free from social ills.

Luckily for Houston, though, the plug-and-play International Style sidestepped any need for sensitivity to context or a regionally shared vision when creating such a new world, and after World War II a few renowned architects were willing to play ball. For two decades beginning in the 1940s, Houstonians microdosed utopia by simply buying buildings that looked like they might belong in an ideal world and placing them here instead. The result was a number of cherished works. Cullinan Hall and Brown Pavilion at the Museum of Fine Arts actually were designed by Mies van der Rohe, and Allen Parkway Village (formerly known as San Felipe Courts and now mostly demolished) demonstrated a willingness on the part of the public sector to buy into his common modern ideals. Even in middle-class residential areas, the swathes of ranch homes mass-developed during this period hold clear modernist sympathies.

Of course, every cluster of suburban enclaves demanded a freeway to downtown, and this period was marked by brutal urban renewal projects in Houston and across the country. As the years bore on, modernist projects that naively attempted to remedy social ills in plan and section did not deliver on their promises of utopia. Critic Charles Jencks wrote that “modern architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972.” On that day, the City of St. Louis demolished the first three of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project’s 33 towers. The carnage of World War II had already brought on an unshakeable disillusionment with modernism—in architecture and in culture more broadly. Still, the literal destruction of Minoru Yamasaki’s disgraced superblocks is a powerful illustration of the cynicism that had set in by the early 1970s. Modernism, both as an aesthetic and as a speedway to utopia, was out.

Houston did not get the memo. As St. Louis continued demolition on Pruitt-Igoe in 1973, our city was poised to finally acquire the wealth and cultural capital to build “real” architecture. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Companies’ embargo against the United States, enforced in retaliation to the country’s continued material support of the Israeli military, led to a high demand for domestically produced oil; prices soared and most of the country suffered bitterly. In Houston, though, the population grew 40 percent between 1973 and 1985 as job seekers flowed into the auto-centric metropolis. For those invested in oil, the city was autopia, totally free of the cynicism afflicting the rest of the United States, and they were eager to buy an image to match.

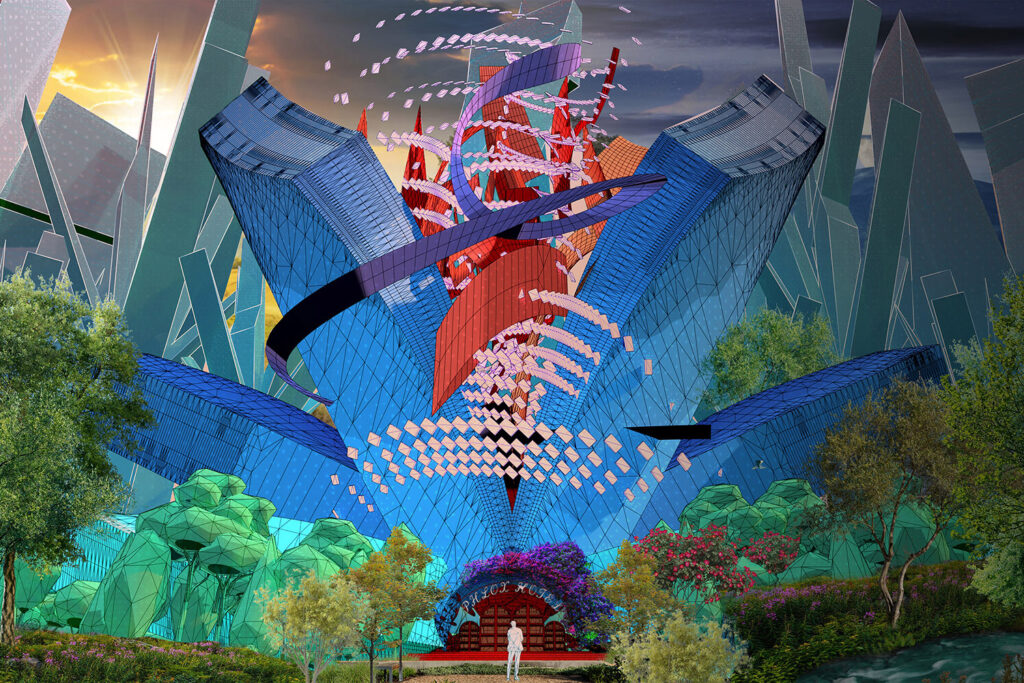

Gerald D. Hines led the charge, hiring Philip Johnson to design Pennzoil Place, Republic Bank, and Transco Tower (among others). However, the developer’s largely actualized delusions of grandeur pale in comparison to some of the paper projects that were dreamt up. For example, in 1970, the Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation developed a conceptual plan for Houston Center. The megaproject would have covered 33 blocks. At this point, the City of Houston was still unable to adopt or enforce any sort of comprehensive plan or zoning ordinance, yet a corporation was nevertheless publishing site plans and renderings for the better half of downtown.

These oil boom years motivated Houston to feverishly annex more and more land, fueled by blind optimism for infinite future growth. Tract homes endlessly spilled from the city’s undeveloped edges, creating a patchy but expansive fabric between the inner loop and the beltway. Although the municipal Planning and Development Department was established in its final form by the 1940s, mandatory development regulations would not be put in place until 1982, so there was little standing between developers and their dreams.

The bubble had to burst. By the mid-1980s, crude oil prices had tanked. Hundreds of thousands of jobs evaporated. Ongoing architectural projects were hurriedly and cheaply wrapped up or abandoned altogether. See-through office towers empty of tenants and devoid of interior partitions adorned the freeways. Houston Center amounted to one building at the intersection of Fannin and Walker Streets. Finally, Houston was being faced with the impossibility of utopia—and the cynicism it had thus far deferred.

When Lars Lerup arrived in Houston in 1993 to serve as dean of Rice University’s School of Architecture, Houston had been clawing itself out of a recession for the better part of a decade, with limited success. With the perspective of a besotted outsider, Lerup set in on understanding Houston—a task to which few if any urban thinkers had singularly dedicated themselves for any extended period of time. Frank Lloyd Wright spoke frankly and for many when he quipped in 1957 that “Houston is an example of what can happen when architecture catches a venereal disease.” Lerup was in many ways the first urban thinker to hold our hand in public.

What Lerup came to understand about Houston was first published in an article titled “Stim and Dross” (1994). Stims, in Lerup’s reading of the city, are “pools of cooled air … precariously pinned in place by machines and human events,” while dross is “the ignored, undervalued, unfortunate economic residues of the metropolitan machine.” Rather than dismissing Houston as a misstep in urban development, Lerup advises that it is time to “close the book on the City and open the manifold of the Metropolis.” In this reading, Houston becomes more than an eclectic combination of misguided investments, instead inspiring an almost sublime terror as the paradigm for the sprawling, decentralized urban centers of our future.

“Stop trying to make Houston a great American city and start trying to support what makes Houston great!”

While he acknowledges the many ways that Houston fails to meet urban studies’ long-established benchmarks for a “successful” city, Lerup takes Houston seriously. He offers us another framework for approaching the city that at least begins the task of appraising Houston’s many centers. These nuclei are precarious, formed as they are by the unintentional overlapping of planned and unplanned systems, but they are also delightful. Lerup’s writing is more observational than instructive. However, action-oriented readers may tease out an implicit admonishment: Stop trying to make Houston a great American city and start trying to support what makes Houston great!

In his introduction to One Million Acres & No Zoning, published nearly two decades after “Stim and Dross,” Lerup writes: “I often find myself wishing for a different city, not out of dissatisfaction, but out of affection for what the city promises.” Surely, most Houstonians can relate to this. We want a city that is more equitable, walkable, affordable, serviceable, beautiful—and we see the redemptive promise of this city in the traces of utopian intent that haunt our tunnels, towers, and townhomes. As we endure to make our city “better,” Houston’s urbanists would do well to take what is already here seriously and honor the utopian echoes that anchor the city’s irreverent and enduring appeal.

How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

An Ambitious Office Tower Redefines Urban Sustainability

A Family’s Legacy of Excellence

How Can Utopic Ideals Be Engaged in Everyday Life?

Picture-Perfect Charm Along the Texas Gulf Coast

PS1200 Builds a Backdrop for Public Life

Exploring the Parallels Between Science Fiction and Architecture

Illuminated Wood Panels, Inserts for Brick Walls, and Fixtures Made from Recycled Plastic, Mycelium, and Hemp

Home, Heat, Money, God: Texas and Modern Architecture

Text by Kathryn E. O’Rourke

Photographs by Ben Koush

University of Texas Press, 2024

Big Little Hotel: Small Hotels Designed by Architects

Donna Kacmar, FAIA

Routledge, 2023

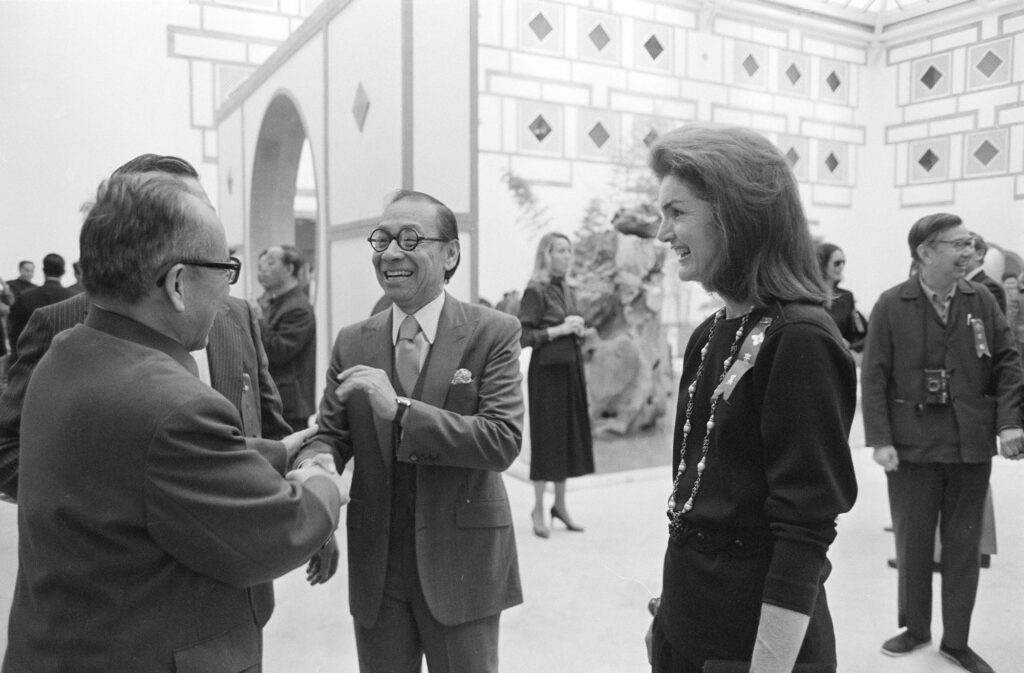

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture

M+ Museum, Hong Kong