An Ambitious Office Tower Redefines Urban Sustainability

How Technological Feats Fuel Our Utopic Visions

“With cities, it is as with dreams: everything imaginable can be dreamed, but even the most unexpected dream is a rebus that conceals a desire or, its reverse, a fear. Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.”

—Marco Polo, Invisible Cities

Throughout Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Marco Polo recounts tales of fantastical cities imbued with elements worth yearning for. Each encounter with a place unfolds as a continuum of impressions and reactions, shaped by where we’ve been and where we are going. Some cities boast intricate spiral staircases, bustling bazaars, or windows that frame breathtaking views. Yet, upon closer inspection, these seemingly idyllic places reveal themselves to be destitute, disconcerting, or utterly unremarkable. Some cities stand abandoned, while others deteriorate, leaving their inhabitants trapped in complacency or dejection. Marco Polo journeys through many cities, some ripe with utopic possibility; yet none achieve that ideal, and most serve as symbols of humanity’s endless desires.

From building sandcastles on the beach to exploring the gravity-defying illustrated worlds of Dr. Seuss, the environments we imagine as children often shape our dreams. These early visions carry a sense of fondness that lingers into adulthood, influenced further by movies and literature that perpetuate shared societal ideals and stereotypes about certain places. Media and popular culture frequently romanticize cities like New York, Paris, and London, fostering subconscious desires to experience these iconic settings. Even without firsthand encounters, these spaces—defined by their sights, forms, and characteristics—can evoke powerful, cathartic emotions. Times Square, for example, may initially captivate with its bustling energy, but over time, its luster eventually fades as its imperfections, like crowded tourist attractions or dirty streets, are revealed. Ultimately, our preconceived notions shape both our aspirations for built environments and the ways we experience them once they become real.

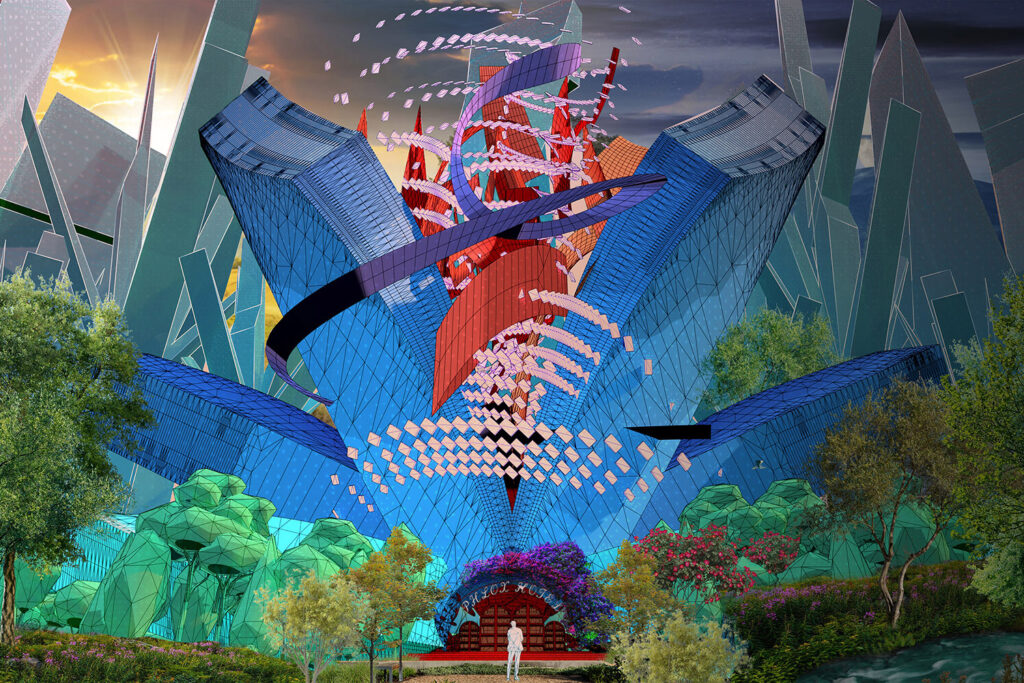

The architectural design process offers its own glimpse into dreamy, unbuilt worlds. Architects, by the very nature of our work, strive to predict the future, designing spaces that are yet to be realized. This act of envisioning the future is like chasing a mirage—an image that remains perpetually at a distance. At the outset of a project, conceptual renderings or illustrations often cast an idealized, almost cinematic vision. Visualizations can easily be embellished on a screen with throngs of people or unexpected elements like hot air balloons or even elephants. While renderings heighten suspense and anticipation among clients and stakeholders, they should do so carefully, ensuring they do not overpromise or set unattainable expectations.

Though the concept design and design development phases aim to set a project’s trajectory as high as possible, as the project progresses, it is inevitably tempered by practical constraints like climate, budget, and code, filtering out its most utopian elements.

Often, these idealistic aspects—the ones that inspired the design’s earliest stages—are the first to be sacrificed. Although the final design may represent a fair compromise of competing factors, it has likely strayed from its initial rose-tinted vision. Of course, the true test of a building comes once it is operational. How will it fare through inclement weather and unexpected conditions? How will it be received by the community? What will its long-term legacy be?

Advancements in construction technology in recent years have given humanity the ability to bring futuristic designs—many that have been dormant for decades—out of the conceptual phase and into reality. Building taller, larger, more unconventional shapes—even constructing on extraterrestrial grounds—is now in the realm of possibility.

Supertall structures—buildings standing 984 feet or taller—seem to have originated in the imaginations of past generations, having often appeared in film and other media around the globe. Today, marketed as a housing solution, they represent one of humanity’s latest materializations of advancement. Despite facing critics and controversy along the way, those involved appear to be proceeding with cautious optimism, hoping that these structures live up to their promised innovation. However, we have yet to see a full life cycle of any of these supertall edifices.

We are, however, beginning to see some of their limitations. Towering at almost 1,400 feet high, 432 Park Avenue in New York City touts itself as the tallest residential tower in the Western Hemisphere. When its condos became available for purchase, the building’s luxury residences were quickly snapped up. However, despite paying millions for a spot in the tower, residents are already plagued with problems: leaks damaging their apartments, elevator outages, and building movement causing loud creaking noises—a supposed hallmark of supertall structures.

At first glance, such problems may seem commonplace in any residential environment. However, it is apparent that as the scale of buildings increases, so do the scale of the problems—and the difficulty in solving them. Standing at 645 feet, Millennium Tower in San Francisco does not technically qualify as a “supertall” building, but it certainly exemplifies the way physical size correlates with escalating challenges. Less than a decade after its construction, the luxury residential skyscraper encountered a structural issue, which was addressed only after its foundation sank nearly 18 inches. This settlement caused an initial 14-inch tilt at the top of the tower, leading to cracks and the eventual closure of a garage elevator. To provide stability that the original foundation, built on soft soil, could not offer, engineers devised a plan that included installing concrete piles into the site’s bedrock. Although the repairs have been deemed complete, the damage was already done, as the valuation of the condos sank alongside the foundation. Plumbing backups, window failures, and various lawsuits may have further tarnished public perception of the so-called high-end living experience, likely contributing to the devaluation of the residences.

Soon, supertall structures will stake their place in Texas, too, and their impact will be observed in real time. When completed, Waterline in Austin will be the tallest building in the state, rising over 1,000 feet. Capitalizing on its proximity to the city’s natural features, the mixed-use development claims that “wellness” and “healthful living” are fundamental to the project. To reinforce this focus on well-being, the project will offer a variety of gym facilities, green terraces, and ample natural light throughout its spaces. But will unforeseen architectural challenges lead to headaches and stress for its users as they have with other supertall structures? Time will tell if this caliber of structure will one day be lamented as a misguided attempt to advance construction science and urbanism, much as historical visions of the future have often been considered outlandish in retrospect. Technological advancements are only as effective as the humans who maintain them; deferred maintenance and other neglect threaten the lofty promises of supertall buildings.

Supertall buildings are only one architectural approach to fulfilling utopian aspirations. A notable pioneer of construction technology was Buckminster Fuller, a visionary whose ambitious concepts were not only conceived but somewhat successfully realized. Fuller spent much of his life searching for innovative solutions to complex design problems. He brought the geodesic dome into public view, presenting it as a practical tool to address global issues such as housing shortages and sustainability.

One of Fuller’s most eccentric proposals was the Dome Over Manhattan, envisioned as a solution to sustainability challenges. His Montreal Biosphere (1967) demonstrated the potential of geodesic design, but its promise of durability fell short when its acrylic shell caught fire during welding renovations. Ultimately, economic, social, and practical concerns prevented the widespread adoption of the geodesic dome as a viable design option—at least not at the mass scale of modular production Fuller had intended.

In 1991, Biosphere 2 was established in Saddlebrook, Arizona, aiming to resurrect Fuller’s utopian pursuit. Designed as a self-contained environment replicating Earth’s ecosystems, the facility also served as a prototype to prove the feasibility of potential space colonies. Between 1991 and 1994, two experiments were conducted, isolating eight participants within the biosphere. Both attempts failed due to issues such as oxygen depletion, the collapse of the ecosystem, and inadequate emergency medical care for the participants. While Fuller’s posthumous influence endures, it remains largely symbolic. His Fly’s Eye Dome, envisioned as a solution for housing and rainwater collection, now stands in Miami as an art installation.

At best, his works remain as memorials and reminders of what he hoped might have been. However, society was enamored by the ideas encapsulated in Fuller’s career. Despite never reaching fruition in the practical sense, Fuller’s tessellated domes became a symbol for a futuristic society, serving as the inspiration for the many self-contained dome cities found in science fiction literature and film. Pauly Shore’s Bio-Dome (1996) directly parodied the Biosphere 2 experiment and the chaos that inevitably ensued. Other movies like Logan’s Run (1976), House of Tomorrow (2017), Spaceship Earth (2020), and Biosphere (2022), and even episodes of The Simpsons, explore similar themes of containment and domed living. Likewise, novels such as Ben Bova’s City of Darkness and Stephen King’s Under the Dome utilized the dome as the backdrop for their respective dystopian societies.

Although not about a dome, Darren Aronofky’s film Postcard from Earth (2003) explores futuristic themes of space exploration and colonization, all while being screened in a near-360-degree cinema housed within a dome known as Sphere, an entertainment arena located in Paradise, Nevada, just outside of Las Vegas. Sphere has captured public attention not only for its awe-

inspiring domed structure, encased inside and out with LED pucks, but also for the immersive experience it creates. There is something distinctly utopian about such experiential technologies. But beyond the captivating optics and aesthetics lies the real challenge of making these ideas function as intended—as isolated, self-contained, and highly controlled environments. The commonality shared by these examples is the desire of crafting a future in which we can control and manage our environment to ensure continued success and homeostasis.

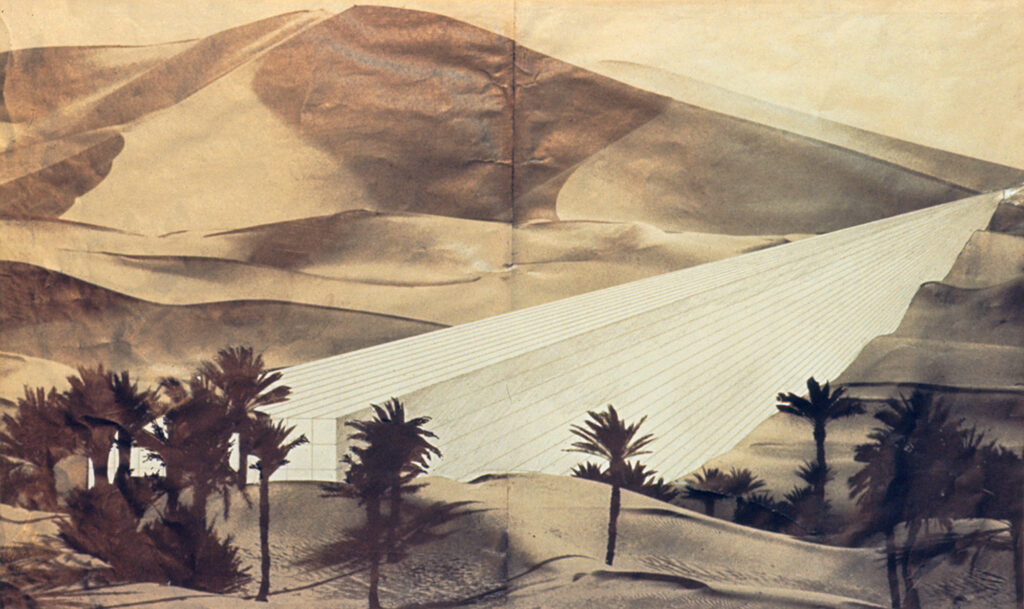

Humanity’s pursuit of a self-contained, highly controlled world as a solution for the future has culminated in its most ambitious expression to date through NEOM, an innovative and hypertechnical development in northwest Saudi Arabia. The name NEOM is derived from a mix of Greek and Arabic, with “neo” meaning “new” and “mustaqbal” translating to “future.” This “new future” reimagines sustainability, industrialization, and entertainment through five different regions: Magna, a high-end coastal city; Oxagon, an advanced industrial hub; Sindalah, a luxury island experience; Trojena, a mountainous tourist destination; and THE LINE, a 170-km-long urban development.

THE LINE, perhaps the most well-known region of the venture, is a self-proclaimed sustainable development that, in the words of the NEOM team, will contain “no roads, cars or emissions…and everything its nine million residents could ever need within a five-minute walk.” This new city takes a paradoxical approach to sustainability, importing the contents of a city into a seemingly empty, desert landscape. The intent, as described by NEOM’s own website, is to combine all the lessons learned from other cities to create “a new city from scratch.” While the buildings may be “smart” and incorporate lush, self-

sustaining landscaping, the opportunity cost of moving hundreds of thousands of tons of materials to shove a city into a naturally desolate environment directly contradicts its purported sustainability goals.

THE LINE is eerily reminiscent of Superstudio’s speculative drawings in The Continuous Monument from 1969-70, which were thought to be so imaginative that they could only be perceived at the time as a dreamy, impossible world. This endeavor critically illustrated what Superstudio described as “the absurdity laid bare”—a radical future in which ornament and human sensibilities are stripped away from the built environment, leaving only that which serves the utilitarian requirements of an anonymous, factory-esque society. Coincidentally, THE LINE’s most widely circulated images show its massive, mirrored facade camouflaging itself in the desert, resulting in a similar expression of anonymity and highlighting its isolation from the world at large. Other images of the development show self-contained webs of interconnected blocks, evoking the dystopian, industrial environment of The Matrix, where humans experience a false reality in their minds, and their physical bodies are arranged within an “ant farm”-like structure in a massive silo.

Interestingly, THE LINE bears a closer resemblance to this dystopian setting than the movie’s depiction of Zion, the last remaining “real world” where genuine human experience is allowed. Unlike NEOM’s vision of success, the radical worlds depicted in The Continuous Monument and The Matrix are presumed to be failures. With cutting-edge technology and some of the world’s most renowned architects, engineers, and planners involved, NEOM stands to become a real-world case study of these hypothetical worlds, along with their financial, geographical, and diplomatic implications. Regardless of whether NEOM succeeds or fails, the irony remains that these so-called socially responsible spaces are built against a backdrop of manipulated natural features of mountains, coastlines, and greenery.

Construction technology has advanced rapidly in recent years, reshaping how we envision building the future. 3D printing, in particular, has emerged as a promising innovation, resulting in various ventures in the Texas area. One notable example is Mars Dune Alpha at the Johnson Space Center, a space designed by BIG and 3D-printed by ICON and intended to simulate the environment of Mars. NASA uses this habitat to simulate equipment and communication challenges astronauts may face, helping to inform how extraterrestrial problems can be addressed to support future missions exploring the final frontier. What once was only possible in sci-fi movies and books is now becoming a reality. As this vision takes shape, the question remains: Is this futuristic dream truly achievable, or is it just a “pie in the sky”?

Such 3D-printed projects raise obvious technical questions—particularly concerning the constructability and adaptability of additive manufacturing in the context of unprecedented environments and different atmospheric conditions. They, also pose profound ethical questions: What will the human experience be like beyond Earth? What will happen to the traditions and culture that have been tied to architecture since the dawn of mankind? Will the human species start afresh with a clean slate? For now, we can only speculate whether building civilizations on celestial bodies could indeed lead to a new utopia.

And the most important question of all: Although anything may be achievable, is it truly desirable?

Architecture is always striving for a utopian ideal. Whether it is a space depicted in popular media, a speculative structure imagined by visionaries, or a futuristic project built to integrate with ever-changing technologies, designers are driven by the pursuit of optimistic outcomes. Architects can gather information based on the client’s anticipated needs and industry trends, but there is no guarantee that the space will be experienced as intended, especially if the project takes years to construct. As prophesied by Rod Serling, the same utopian ideal that we pursue, when taken to extremes, can result in unintended negative perceptions and consequences.

“A scared, angry little man who never got a break. Now he has everything he’s ever wanted, and he’s going to have to live with it for eternity, in the Twilight Zone.”

—Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone

Although the goal of these endeavors is to achieve something extraordinary, no project is without its faults. The term “utopia” translates literally to “no place” in Greek; perhaps hinting that no such perfect place exists.

Camille Vigil is an architect in Dallas who works primarily on faith-based projects.

Tanvi Solanki, AIA, is a Houston-based architect who works with sustainable design and laboratory planning.

An Ambitious Office Tower Redefines Urban Sustainability

Exploring the Perils and Delights of Houston’s Irreverent Approach to Urban Development

A Family’s Legacy of Excellence

How Can Utopic Ideals Be Engaged in Everyday Life?

Picture-Perfect Charm Along the Texas Gulf Coast

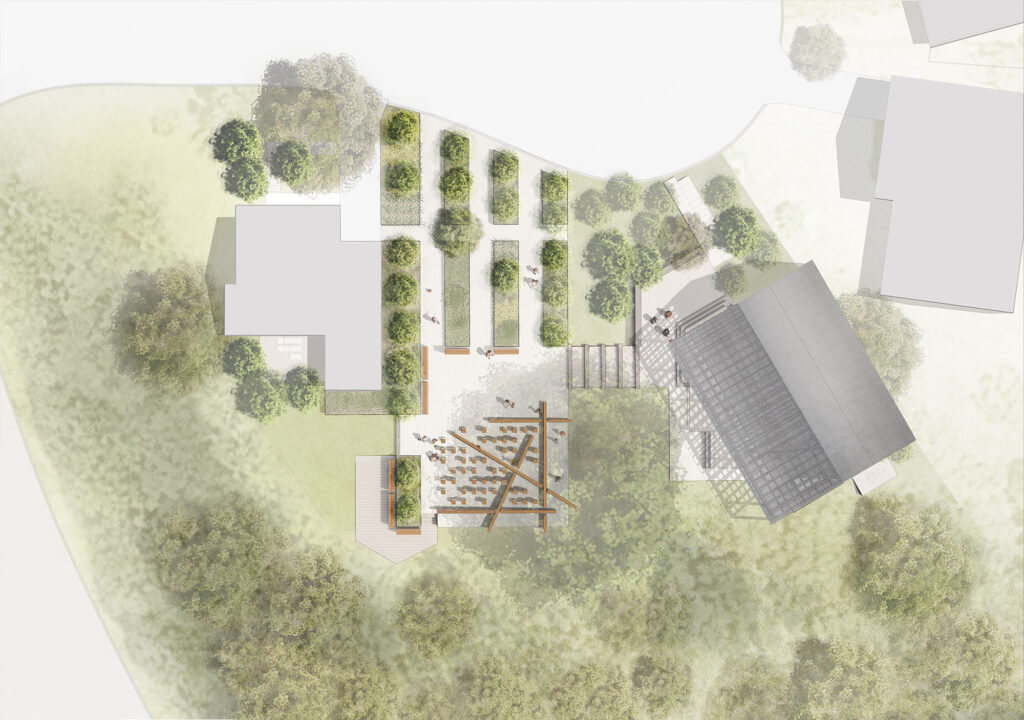

PS1200 Builds a Backdrop for Public Life

Exploring the Parallels Between Science Fiction and Architecture

Illuminated Wood Panels, Inserts for Brick Walls, and Fixtures Made from Recycled Plastic, Mycelium, and Hemp

Home, Heat, Money, God: Texas and Modern Architecture

Text by Kathryn E. O’Rourke

Photographs by Ben Koush

University of Texas Press, 2024

Big Little Hotel: Small Hotels Designed by Architects

Donna Kacmar, FAIA

Routledge, 2023

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture

M+ Museum, Hong Kong