Plans for Redevelopment of San Antonio’s Broadway Corridor Still Contested

Urban design has always occupied the intersection of politics, social science, and economics. In an age where the town square has gone digital, physical public space has become a contested reality. While social media users too often use public digital platforms with disgruntled attitudes, a level of courtesy is still expected on our city streets. This fact heightens tensions around redevelopment projects, as urban environments seem to be one of the only avenues left for neighborly interaction. This physical landscape has the newly added pressure of contributing to a city’s “brand”; however, it is far more lasting in the memory of visitors than a short-lived Instagram post. The recent dispute over the narrowing of the Broadway Street Corridor in San Antonio highlights how public space has the unique burden and opportunity to function as a platform for bringing communities together and showcasing “place” as distinct from its digital counterpart.

Recently, a series of planned improvements to local transit corridors have suffered due to a breakdown in partnership between the state of Texas and its cities. The rift is due in large part to differing visions held by each entity regarding some of the most beloved main streets across the state. Nowhere is the situation better highlighted than in San Antonio’s Broadway corridor. Broadway currently operates as a six-lane throughfare under the provision of the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT). Flashback to 2017: The street was to be gifted to the city of San Antonio by TxDOT, with the vision of creating an exemplary complete street in keeping with the city’s desire for a walkable, multimodal corridor.

The 2017 voter-approved bond program allocated $42 million to “reconstruct Broadway from E. Houston to Hildebrand with curbs, sidewalks, driveway approaches, bicycle amenities, lighting, drainage, and traffic improvements as appropriate” and seemed to provide for a new complete street. However, more than six years later, the portion of Broadway from the intersection of Interstate 35 to Hildebrand Avenue remains unaltered. The state government has gone back on their initial agreement to transfer Broadway to the city of San Antonio, largely in reaction to initial plans to convert the corridor into a four-lane boulevard with bicycle lanes. The city’s proposal runs contrary to Plank 63 in the state’s GOP platform, which “oppose(s) anti-car measures that … impose ‘road diet’ mandates designed to shrink auto capacity and/or intentionally clog vehicle lanes to force deference to pedestrian, bike, and mass transit options [so as] to protect drivers from these California-style, anti-driver policies in Texas.”

While the community is divided in their opinions of a “road diet,” residents clearly understand the special nature of the corridor. “There is definitely not consensus,” remarks Ruth Rodriguez, president of the Mahncke Park Neighborhood Association. “We would love improved streetscapes. We’d love safer sidewalks. We understand that it is really not safe for a bicyclist on Broadway … but by the same token, we also know that Broadway is a very, very busy street.”

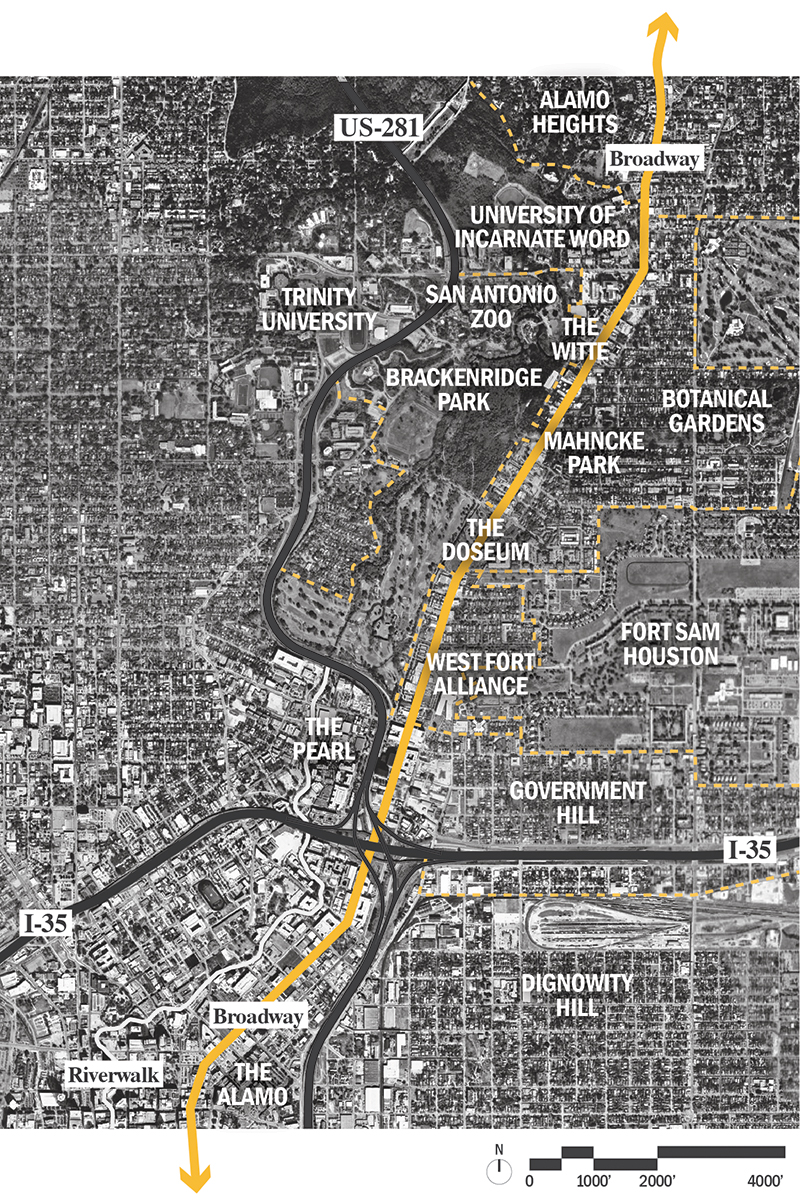

While U.S. Route 281 does the brunt of the work for those that commute from the city’s northern neighborhoods, traffic does increase along Broadway during local rush hour. Residents in Mahncke Park, Westfort Alliance, and Government Hill — neighborhoods flanking Broadway — initially expressed concerns about increased traffic through their neighborhood associations. However, in general, the communities have expressed excitement for the many cultural institutions along the Broadway corridor and understand the need to showcase them along a planned boulevard. “What has happened around the Pearl area is just amazing, and we would love to see more of that dynamic,” notes Rodriguez. “Places like what was [Schulz] Nursery [vacant since 2019] should be a hot spot.”

Broadway is arguably more than a road; it is seen as a greater asset for the city. The local nonprofit Centro San Antonio refers to Broadway as “one of San Antonio’s Great Gateways” and “a critical artery in and out of downtown” on their website. The organization hopes that improvements will “connect (San Antonio’s) cultural institutions, enhancing the overall experience of the city,” while also spurring development. Ideally, the city’s recent cultural work, which includes the renovation and expansion of the Witte Museum & Mays Family Center and the DoSeum children’s museum (both projects by Lake|Flato Architects), would be knit together with established institutions like the San Antonio Zoo, Brackenridge Park, San Antonio Botanical Garden, and the McNay Art Museum, connecting these uptown destinations to well-known landmarks like the River Walk and the Alamo. “You have all these assets lined along [Broadway] and the river,” remarks Glenn Huddleston, the owner of several properties along Broadway. “The more people that move to San Antonio, the more people are going to revere this area of San Antonio — if it’s done right.”

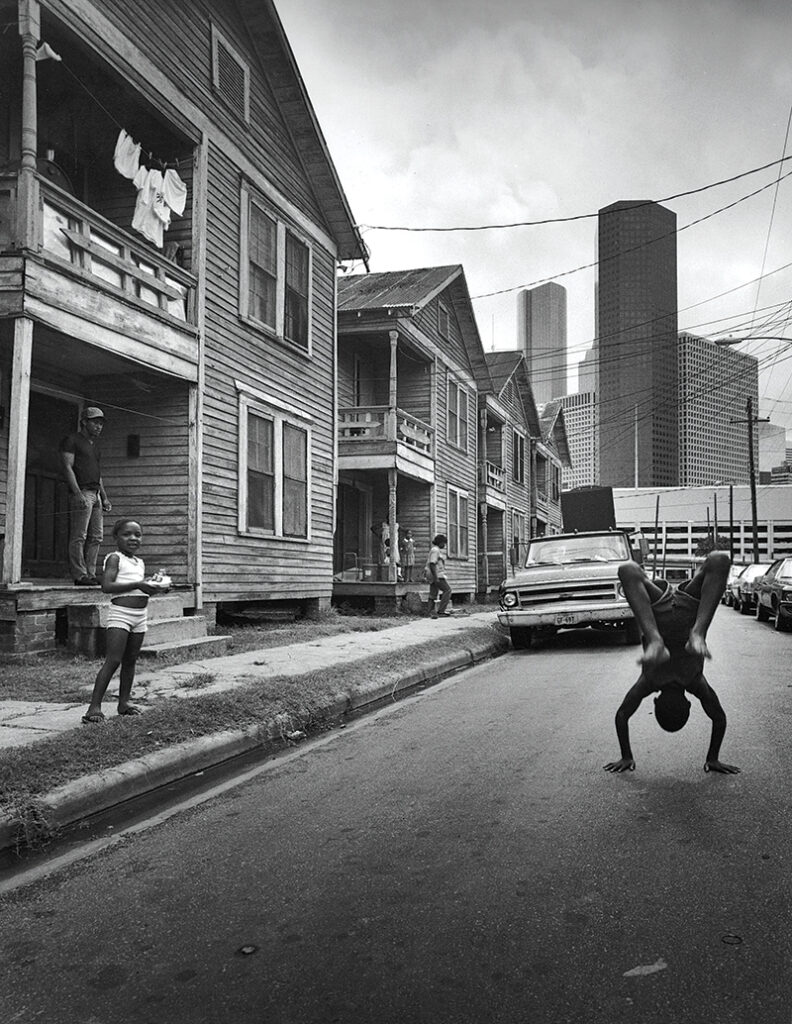

What is disheartening for most is the standstill in improvements affecting Broadway from Josephine Street to Burr Road and the associated lack of transparency and vision in TxDOT’s planning. In contrast to the nearly completed section of the Broadway corridor delegated to the city, which was trimmed down to a four-lane thoroughfare complete with bicycle infrastructure along nearby Avenue B as well as thriving dining options and new retailers, the northern portion of Broadway from I-35 through the Alamo Heights border has several vacant properties that are over 3,000 sf. The vacancies don’t bode well for the city’s image: Buildings once gleaming with potential now sit vacant after an already crippling lockdown, reading as post-pandemic casualties to the average passerby. Undoubtedly, the success of these businesses is tied to the context of the boulevard. When asked how the surrounding infrastructure contributes to the success of businesses on the corridor, Huddleston succinctly replies: “Fundamental.”

Huddleston envisions a “great street … two lanes in both directions, an esplanade down the middle of it with hybrid live oaks, a boundary of trees on the outside,” enabling one to “drive down from Burr Road all the way to downtown San Antonio in a canopy of shade.” Huddleston believes this would add to the quality of the pedestrian experience, thus activating the street, businesses, and the larger community. His vision lies in stark contrast to the current experience of Broadway as a six-lane “highway.” With drivers traveling at a standard rate of 10 miles per hour over the 35 mph speed limit., the potential contributions of these vacant buildings to placemaking — the most noteworthy of them being the classic mid-century Inter-Continental Motors building, designed by O’Neil Ford and owned by Huddleston — is generally overlooked.

Regarding working sessions focused on Broadway with the Midtown Tax Incremental Reinvestment Zone, Huddleston says: “It was really funny: You could have elderly people; you could have people with young children; real estate guys … business owners — and it all came down to two things: trees equaling shade and sidewalks.” From a business standpoint, says Huddleston, “if you can’t get them out of their cars, they aren’t going to be an asset to your enterprise, whatever that enterprise is, even a park.” With a 100-ft right of way on the stretch along Josephine Street to Burr Road, the opportunity to make a place for the community and businesses is like no other. Stakeholders like Huddleston find it discouraging to see that potential slip through the community’s fingertips due to a political scuffle.

While the revised TxDOT plan for the portion of Broadway that is in limbo will contribute $16 million to a safety-focused mobility improvement project, it will not offer improvements to the impersonally scaled, unbuffered road, which could better the physical framework for future points of attraction. As Danish architect and urban designer Jan Gehl, Hon. FAIA, puts it: “Cities and building projects of modest dimensions, narrow streets, and small space … are comparably perceived as intimate, warm, and personal. Conversely, building projects with large spaces [and] wide streets … often are felt to be cold and impersonal.” This leads us to question how businesses along the six-lane portion of Broadway will attract customers, as they would need to promote their establishments with the large-scaled, overt signage that a highway would warrant but that current zoning prohibits. With exception to restriping and ADA-compliant upgrades to existing sidewalks, little will improve for the properties along this portion of Broadway, leaving a sparse backdrop for an already empty scene.

Certainly, San Antonio would like to set the stage as a city that appeals to both visitors and residents of Broadway. What is said about San Antonio in the digital realm cannot replace the value of firsthand experience on its main street. For the community and stakeholders, Broadway is more than a road and is more akin to an “influencer,” showcasing the special place that is San Antonio. Ultimately, state and local leaders should aim to improve the boulevard as the public face of San Antonio, rather than characterizing improvements as a “diet,” taking advantage of the opportunity to brand the city as something unique, promising, and welcoming.

Noel Kuwabara is a registered architect in Texas and serves as faculty at San Antonio College. She holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Syracuse University and a Master of Science in Urban Design from the University of Texas at Austin.

Also from this issue