Decked Out

Auxiliary paints a bright future for ADU construction in Houston.

Project Auxiliary ADU

Location Houston

Client Avenue Community Development Corporation

Architect Rice Architecture Construct

Contractor Rice Architecture Construct with Boxprefab

Structural Engineer Silman Associates

Mechanical Engineer Wylie Engineering

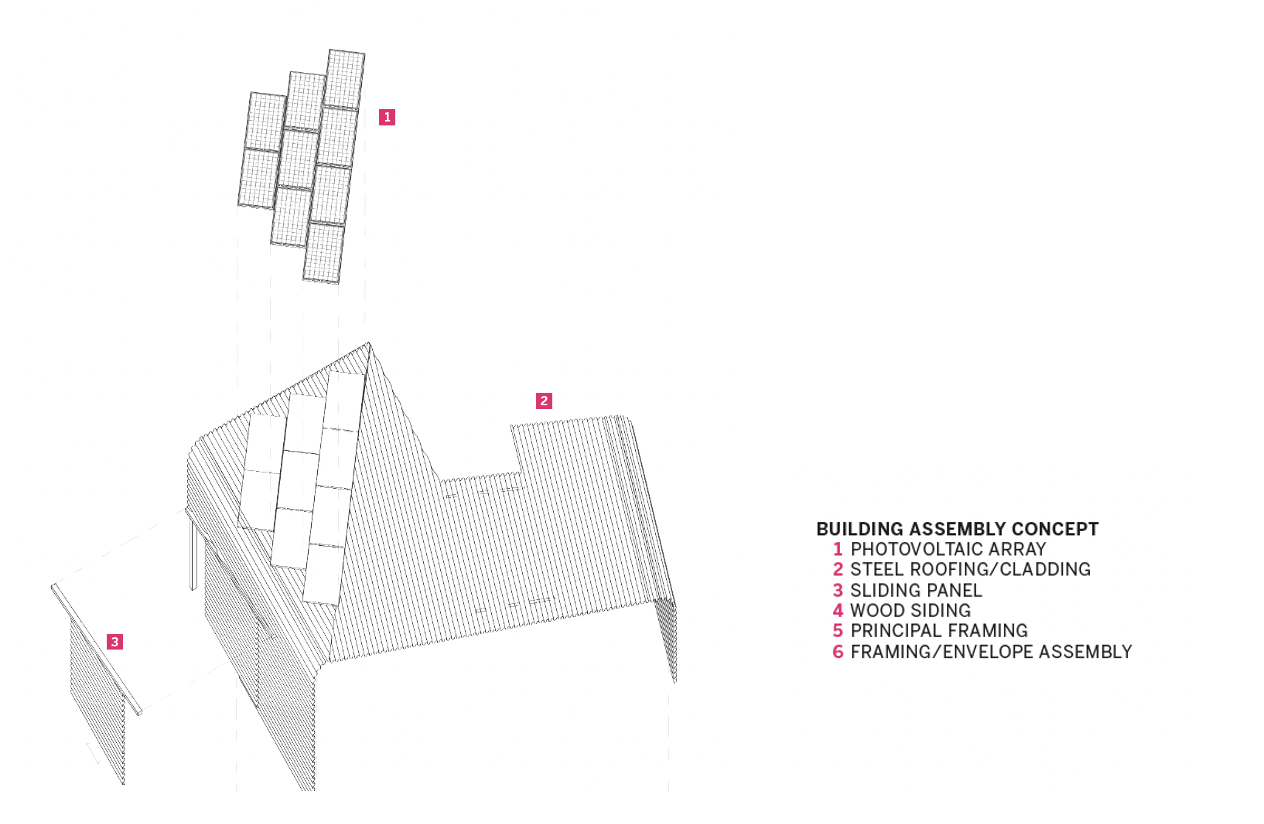

Tucked behind a row of colorful historic one-story houses in Houston’s First Ward neighborhood, Auxiliary, with its friendly peach-painted wood siding, fits right in, though the corrugated metal sheet that wraps the structure is a contemporary feature that sets it apart. Barely noticeable atop the roof sit a series of solar panels, installed with the intent of schieving net-positive energy production.

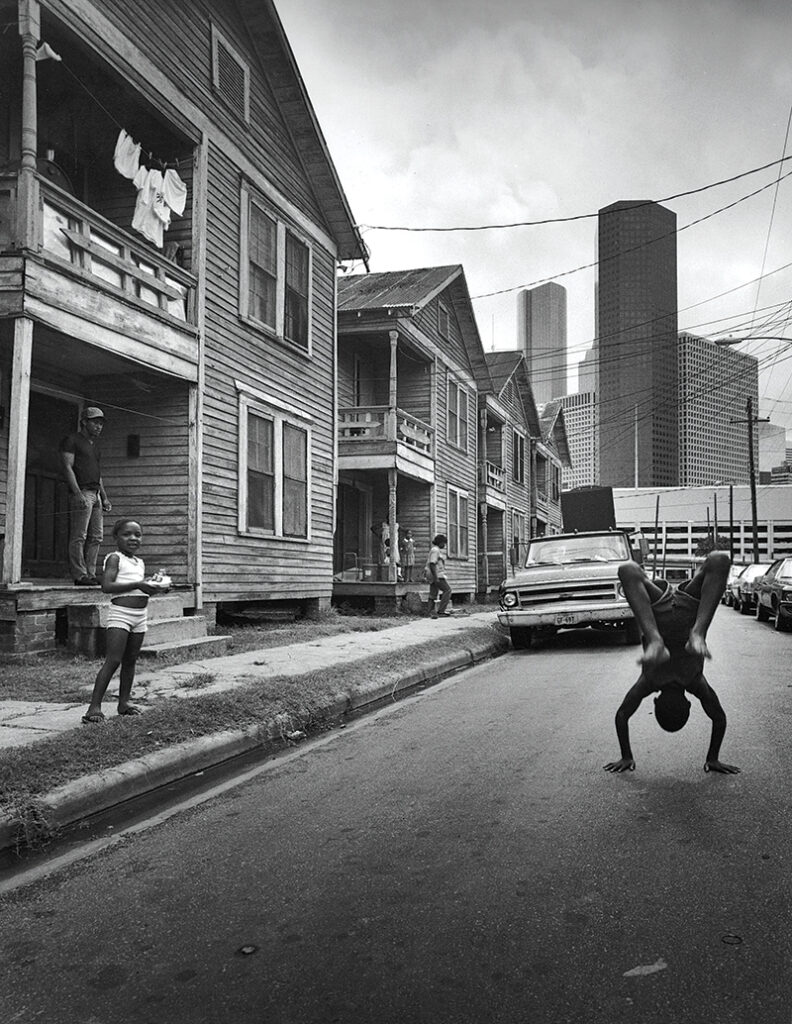

The accessory dwelling unit (ADU) was constructed over the course of two years by a team of Rice University students as a part of Construct, a design-build program for undergraduate and graduate students within the School of Architecture that has been contributing to underserved communities since 1996. Initially known as the Rice Building Workshop, the program has had a long relationship with numerous local organizations over the years, including Project Row Houses, an initiative in Houston’s Historic Third Ward to provide affordable housing and a hub for art and community development. Recently, Assistant Professor Andrew Colopy and Professor in Practice Danny Samuels, FAIA — co-directors of the program — have led studios and seminars researching ADUs and how they can address Houston’s housing needs. “That’s allowed us to connect to a much bigger conversation around issues of housing,” says Colopy. “Each one of the studios has addressed a different kind of topic. This one was really focused on energy efficiency and energy sustainability.”

The 618-sf, one-bedroom ADU was designed as two separate volumes that can be conditioned independently. The students modeled the timing of occupancy throughout the day, the desired temperature set point, and, with those data in mind, where energy could be conserved. The western volume contains the bathroom, bedroom, closet, utilities, and laundry room and can be set to a comfortable temperature when the occupant is sleeping. During that time, the eastern volume, which houses the kitchen, living, and dining areas, can prioritize energy efficiency over comfort.

The design is based on the traditional dogtrot housing typology, which incorporates a central porch that bifurcates the two volumes, harnessing passive ventilation as it provides shade. Large windows open onto the central porch to take advantage of indirect lighting and natural ventilation, and two yellow doors lining the porch provide a cheerful pop of color. Continuous sightlines from one volume to the next create the illusion of a single large space. The ADU’s outward-facing walls have few windows, a design move intended to help conserve energy and provide privacy, a much-needed feature due to the proximity of the surrounding homes.

The students were tasked with creating a design that would not only produce enough energy for its own operations but also subsidize the energy needs of an existing primary dwelling. In principle, extra power from the ADU can subsidize the existing dwellings, but logistically the ADU cannot provide energy to dwellings that are not on the same property (though energy is returned to the grid). In the fall of 2019, a design studio of eight students worked in pairs, with each team producing a prototype. Building assemblies were computationally tested over 19,000 potential sites and later integrated into full energy models. At the end of this process, the most energy-efficient project, designed by students Kati Gullick and Madeleine Pelzel, was selected to be built.

For Auxiliary, Construct received an Energy and Environment Initiative grant from Rice University and was also supported by the Susan Vaughan Foundation. In the winter of 2019, Colopy and Samuels partnered with the Avenue Community Development Corporation, a nonprofit builder of affordable housing in Houston, who funded the difference and provided a site for the project. In addition, Avenue CDC managed the necessary urban improvements outlined by the Construct team, including rebuilding the driveway and sidewalk.

The students had many considerations to account for on the site, most notably the site’s orientation since it would affect the ADU’s ability to produce solar power. The two lots owned by Avenue CDC on which Auxiliary is located house two bungalows to the south of the site and an ADU built in the 1930s to the west. There are also townhouses to the east that were a major determinant of how the solar panels would be situated on the roof, since their height shades the site for the first half of the day. The team took advantage of a fence along the north side of the site as an unobtrusive place at the back of the ADU to locate building services, a design move that prevented the need for penetrations in the roof and interference with the solar panels. The solar panels are accompanied by a 10-kW solar battery that can store energy locally in the battery for use on a shady or rainy day. Once charged, it sends excess energy back to the electric grid. The solar panel installer and provider Freedom Solar donated its services and materials and is partnering with PearlX, a company that monitors the project’s energy usage and provides data to the Construct team.

As part of the assignment, the students were also asked to design the building envelope in a new way. Double-stud construction within the roof and one wall was used to hyperinsulate the envelope. Gullick and Pelzel initially designed the wrapped roof to pull the two volumes together as one continuous element, both aesthetically and practically. To support this form structurally, the design team created a “portal frame” — a frame that spans each half of the building. Since the connection between roof and wall is not a typical gable construction, the students needed a new approach: Double studs and double joists were set apart from each other and attached with CNC plywood plates, minimizing the connection between the two studs, which in turn reduced the amount of material needed as well as the time required for on-site framing.

The frame’s plywood plates also allowed the team to design a pitched roof that would be optimized for solar angles. “That was actually part of the design of the prototype — for it to be flexible enough so that no matter where you plop this thing down, you would be able to put solar panels on one part of the roof, and they would be in more or less the correct orientation,” says Gullick. “With a pitched roof, you can really optimize the angle.”

Licensed contractors were hired to install the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems, but the students and Construct co-directors built the structure of the ADU, along with the cladding and all interior finishes, themselves. Due to the time commitment required for permitting and the constraints of an academic schedule, the permitting process was primarily handled during the summer of 2020 by two students overseen by Colopy as architect of record. Once the permit was finalized, construction took three full semesters and one summer. Throughout the two years of the project’s realization, 56 students were involved with research, design, drafting, and construction. The project was completed in the spring of 2022, and a student has been living there since August of that same year. Pelzel reports excitedly: “A lot of changes were made. There were a lot of things that had to become more specific, but it’s amazing to see this initial image in our minds come to life and have someone actually living in it.”

The biggest challenge the team faced was the project’s unfortunate timing: Construction began at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the instructors had to receive special permission from Rice University to continue with it. Throughout construction, team members were masked and did their best to socially distance. The project’s schedule suffered from shipping delays, and once-affordable materials suddenly exceeded the budget, requiring adaptability. For example, the team had initially specified gray cedar cladding, but once the cost of the material skyrocketed to five or six times the budgeted amount, the team opted to use pine shiplap cladding instead. This pivot in material presented the opportunity for the project to respond to its colorful context, the students painting the wood siding to complement the other houses.

Due to single-family zoning requirements, ADUs have been illegal in many municipalities across the United States for some time. But in the past five years, many cities have started to legalize their development. Because of Houston’s lack of zoning, ADUs have always been legal and quite common in the city, although parking and other requirements remain stricter in comparison to those of cities now liberalizing the structures.

In Auxiliary, a bike rack fulfilled the parking requirement and created a significantly more pedestrian-friendly layout for residents. Houston’s policies on ADUs are currently being reconsidered to be more accommodating and supportive of development. Foreseeing a positive future for ADUs in Houston, Colopy says: “There are over a million single-family lots in the Houston Metro area. If you were to put an ADU on every one, you could provide housing to support the predicted population growth through 2040, without building a single new road.”

Construct is aiming to raise awareness around the need for ADU development and the negative effects of focusing new construction on single-family homes. ADUs strengthen the urban fabric by creating more affordable housing, by decreasing environmental impact, and by accommodating a range of family types like multigenerational and single-parent households. Construct has successfully guided students through the research process and allowed them to realize their ideas through Auxiliary as they set a precedent for future ADU expansion within the city of Houston.

Pooja Desai is a graduate of the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design at the University of Houston and a designer at Protolab Architects.

Also from this issue