Uncommon Courtesy

Boston Commons, a 15-unit community on San Antonio’s East Side, listens deeply to its formal, social, and climatic context.

Client Ben Bowman

Architect Cotton Estes Architect

Architect of Record/Contractor Assets & Architects

Structural Engineer 13th Lv Structural Engineer

Civil Engineer Dye Development

You can’t talk about infill housing without talking about gentrification. It is, so far, the story of the century for America’s cities. While the foundations of gentrification are economic and independent of any formal expression, the phenomenon often manifests itself as big houses on small lots, close to downtown. In these big houses live perfectly nice, often well-meaning but reliably clueless professionals who are as certain that gentrification is a grave problem as they are that they are not a part of it.

Boston Commons in San Antonio is different. Comprising 15 new units in historic (and historically Black) Dignowity Hill, the first neighborhood east of downtown, the project proclaims its deference as loudly as it is permissible for it to be proclaimed. The development’s eponymous street is a single block long, tucked between two through-streets, so the whole project is almost invisible to most passersby. Even if you did choose to stroll down Boston Street, perhaps only the crispness of the curb would alert you that development had occurred.

This modesty continues in the scale and arrangement of its buildings. There are eight structures on the site, ranging from 800 to 1,600 sf, comfortably below the average size of historic homes in the area. Nothing is over two stories tall. The palette of stucco walls, wooden porches, and metal roofs blends easily into the context. There are just enough crafted choices — the whimsy of the control joints, rhythm of the exterior lights, and deck-to-railing detail — that the overall lack of fuss feels driven more by aesthetics than economics.

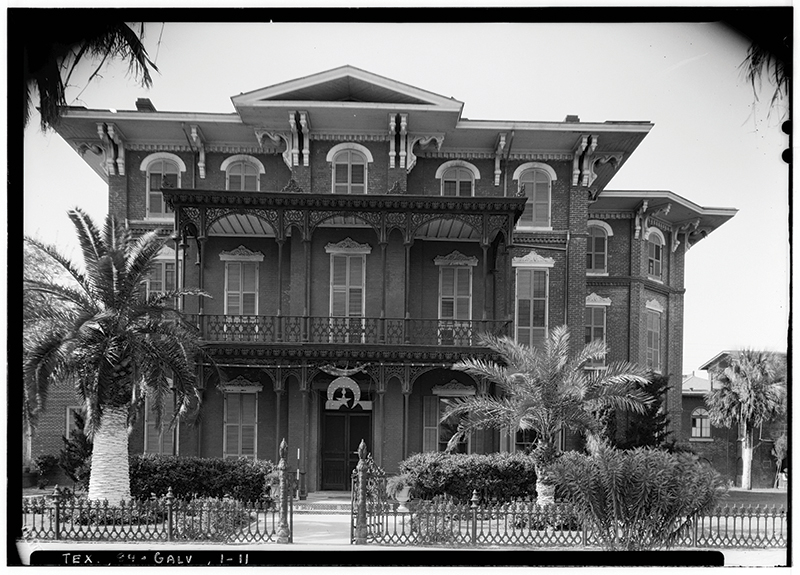

Many of these choices draw from a home on an adjacent property, one of the first in the neighborhood. While not technically a part of the project, this 1910 Folk Victorian was renovated at the same time Boston Commons was underway, and the architects of the two projects collaborated closely on the viewshed, shared outdoor space, contextual integration, and so on. A distinguished project in its own right, the house is clearly a close confidant of the Commons, an elder cousin providing wise counsel on how to mature with dignity.

Boston Commons is deceptively dense. The floor area ratio is an unassuming .41, a metric four times the surrounding average, but just the sort of density on which downtown neighborhoods thrive. Where does all this density come from? In short, from moderation — in terms of space for both humans and cars. The average unit size is small. The private worlds of bedrooms and baths are especially compact, leaving generosity for the living rooms. Cars are relegated to the perimeter of the project: All parking is either parallel off the street or head in off the alley. The site also slopes toward this improved alley, naturally obscuring the cars from the communal outdoor spaces and granting generous views of downtown.

This strict approach to parking offers freedom for residents. Rather than the expansive concrete parking lanes that dominate outdoor space in typical infill projects of this density, Boston Commons boasts — and now really is the time to boast — a shared central open space of definitive humanity. The living spaces open to this central spine, with the bedrooms tucked behind. Design architect Cotton Estes, AIA, aptly calls this an “inner life between buildings.” It is also simply good architecture, where the buildings respond to one another rather than to just a parking ratio or zoning envelope. Boston Commons is a stellar lesson that plain buildings sited magnificently are far superior to magnificent buildings sited plainly.

The project’s sustainability features stem naturally from its values of community and stewardship. A 24.4 kW solar panel array produces renewable energy; nearly 100 percent of stormwater is either retained or detained on site; and 100 percent of the landscaping is dedicated to rain gardens, native xeriscaping, and the community garden — it’s a responsible neighbor in quantitative metrics as well as qualitative ones.

When asked if this is a difficult model to replicate, the team doesn’t hesitate to answer. It is. Systems from financing to permitting to construction are simply not set up to work at this missing-middle scale. That’s a big reason why it’s missing. It’s also the big reason behind Ben Bowman’s decision to develop this project.

“If you want to go buy a $350,000 home, you don’t have too much trouble — there are lots of ways to do that because the system is set up for that,” Bowman says. “So not too many people come and ask me about that. But I can’t tell you the number of people that say, ‘Hey, do you have an extra room I could rent?’ or ‘Do you know of a backhouse that’s available?’” Intentionally developed for the rental market and with rates serving those making from 57 to 144 percent of the area median income, this project offers inherently affordable housing that provides 15 answers to such inquiries, including six deeply affordable co-living suites.

Just as community is at the physical heart of Boston Commons, it is also central to the project’s intangible aspirations. The team worked at the intersection of architecture and real estate development, thinking deeply about whom they were designing for and how the project would be accessible to them. Hairstylists, landscapers, firefighters, teachers; interns, families, retirees; transplants, locals, and re-locals — the project aspires to have a place for all.

And so, we come back to the core issue. It would be ridiculous to expect this project to solve gentrification (spoiler: it doesn’t). But it is the perfect foil to the typical infill development that plays rough with its neighbors, extracts the highest possible rents, and suffocates the site in concrete. Boston Commons is a credible argument that you can achieve ambitious density at affordable rents while harmonizing virtuously with the historical fabric. Hopefully, more hard work by advocate-practitioners like Estes and Bowman can help to change systems and make such projects far more, well, common.

Ben Parker, AIA, is an architect at Overland Partners in San Antonio.

Also from this issue