Mirror, Mirror

Dallas’ iconic Fountain Place office tower finally has the sibling promised by its original 1980s master plan, and — surprise! — it’s residential.

Architect Page

Interiors Page

Client AMLI Residential

Contractor Archer Western

Structural Engineer IMEG

MEP Engineer Page

Branding and Graphics Page

Landscape Architect Talley Associates

Architects don’t do large, pure geometric statement buildings often anymore. Fountain Place Residences, in downtown Dallas, is a decided throwback to a time when glass-clad, minimally articulated shapes, at large scale, were an exciting area of formal study for architects. Some of the resulting buildings were famous, such as John Portman’s Peachtree Plaza Hotel or César Pelli’s Pacific Design Center, where the glass framing was kept to the bare minimum so the form could be as uninterrupted as possible. These buildings were meant to be viewed and understood as abstract sculpture on the skyline. The movement advanced the modern idiom of the glass and steel skyscraper to its logical final step: no steel; only glass. These types of buildings depend on context for their urban presence and to give them something to reflect (or refract) in their crystalline, mirrored surfaces. Somewhere in the late 1970s and early 1980s, postmodernism led to a different expression for high-rise buildings: stone, brass, and historical references. Fountain Place, perhaps the most refined and carefully wrought of the pure geometry buildings, completed as it was in 1986, is valedictory for the style, the literal end of an era.

The original Fountain Place master plan was conceived by the late Henry Cobb, FAIA, principal of Pei Cobb Freed (PCF). It proposed two towers, only one of which was completed. It is coolly elegant, visually arresting, innovative, and inscrutable. Like many of the buildings designed by PCF during this period, it is a testament to relentless resolution and refinement of a seemingly simple and straightforward design paired with complex detailing and cutting-edge technology. The master plan featured another departure from the tower-in-a-plaza model: The building rose from a complex and verdant water garden, replete with 172 choreographed fountains set in a bosque of cypress. People loved this garden, designed by Dan Kiley and Peter Ker Walker. It became the tower’s most popular feature, drawing visitors in large numbers and making it one of downtown Dallas’ most trafficked public spaces. In 2011, the Texas Society of Architects recognized the building with its 25-Year Award.

After the ownership of Fountain Place changed, the opportunity to build a second tower on the site recently became possible. But, rather than adding another office building, market conditions suggested a residential building would be the best bet. Long a commercial center that emptied out at night, much of downtown Dallas’ older commercial building stock has been successfully converted into residential property, and new towers are being constructed in earnest to house the ever-growing number of Texans interested in living an urban life. AMLI was selected to develop the tower, and Page as the architect. The two entities have a history of working successfully together on other projects and a shared belief in good design.

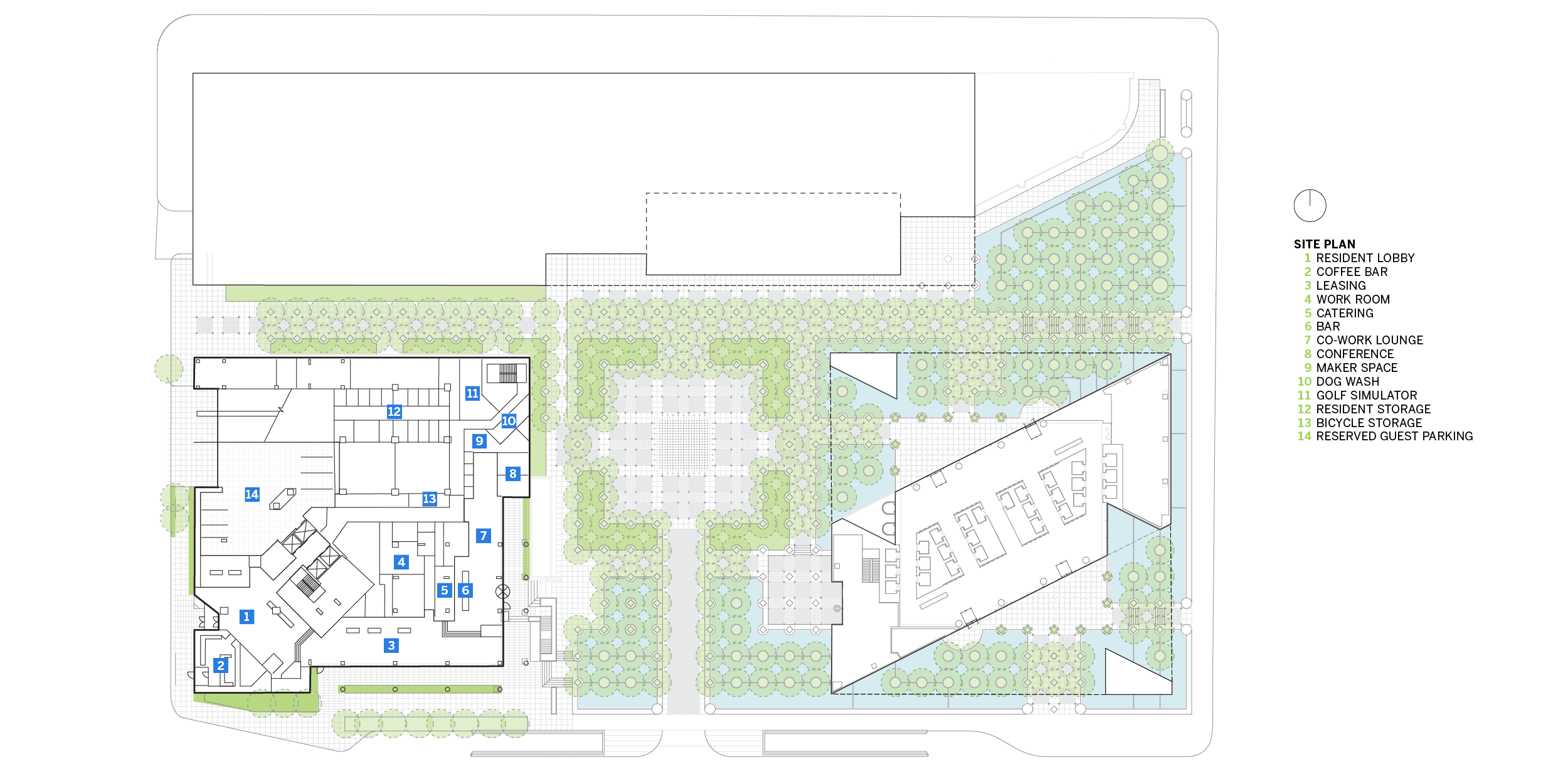

The new 45-story tower rises from a plinth that matches the footprint of the PCF building. Page felt this was a design “given,” the key to allowing as much of the Kiley and Walker gardens to remain in place while completing the original master plan. This decision realized the well-defined and gracious plaza, first envisioned more than 35 years ago. It is a wonderful space; the combination of water and now very mature trees is arresting and strikingly un-Dallas. Refined and kinetic, the fountains create an audible as well as a visual experience, unusual in an urban setting. The residential tower is set diagonally on top of the plinth and is oriented to create a sympathetic dialogue with the older structure. It also allows its narrower footprint to have the same visual heft as its much larger sibling. Because you rarely see the two towers simultaneously, their visual presence is well balanced — no easy trick with such different programs. Page experimented with a variety of standard available glass colors to find an approximate match to the existing tower’s reflective green glazing. They even installed test panels in the original tower to identify the most sympathetic option.

The public interiors of the building are a counterpoint to its cool glass skin. These are designed to be more inviting, warm, and, frankly, residential, though they feel more like an upscale hotel in character. The lobby, a far cry from that of a typical apartment, features sophisticated spaces, in a variety of scales and functions, beautifully furnished and oriented to the plaza with its fountains and gardens. The art program, like all of the interior appointments, was carefully curated by Page.

The units are spatially rich and well-detailed, clearly targeting an upscale tenant. The views are commanding, and the floor-to-ceiling glass brings downtown Dallas fully into the rooms. One forgets the power of full-height glazing and the sense of expansiveness that accompanies it. Some of the units feature walls of sloped glazing. The proximity to the original Fountain Place makes that building a strong visual presence for many residents. The new building departs from the original in several ways, but one of the most noticeable is the inclusion of balconies on the exterior — an owner requirement, to provide exterior access for the otherwise hermetically sealed units. These balconies create a texture on the exterior, but to be in them, with their glass handrails, is thrillingly vertigo-inducing, particularly on the upper levels. It is a nice gesture to have outside access, but it’s a little scary to be out there.

As second acts go, this is a good one. Fountain Place Residences is a fitting last piece to a long-incomplete urban set, and it is pleasant to look at and be around. Working with their clients, Page has done a remarkable thing — created a suitable companion and robust counterpoint to a Dallas icon.

Michael Malone, FAIA is the founding principal of Malone Maxwell Dennehy Architects and president of the Texas Architectural Foundation.

Michael Malone, FAIA, is the founding principal of Malone Maxwell Dennehy Architects and an adjunct assistant professor of architecture at the University

of Texas at Arlington.

Also from this issue