Detention

What lessons can we learn from examining a history of designing detention? And why is the detention center a building of critical and national importance? Building immigrant processing stations, detention centers, and alien prisons has its own history, yet little is known about the specifics of that design history, spanning from the building of Ellis Island in 1892 to the dozens of quickly erected, sprawling detention facilities found throughout the United States today. The detention center is singular. As Immigration and Customs Enforcement asserts, the “legitimate restriction on physical liberty is inherently and exclusively a governmental authority.” Stripping individuals of their freedom to move is an awesome (and terrifying) power granted to the government alone. The architecture of detention is also the environment in which many migrants and asylum seekers are “welcomed,” and where many vulnerable persons interact directly with the spaces and mandates of the State. Finally, examining the architecture of detention raises questions about immigration and detention policy and the intent of such policy as expressed through its physical infrastructure. Detention centers are places to quarantine individuals who are awaiting a legal process that will determine if they are imprisoned, deported, or released. Legally, they are “administrative” processing centers. This has been the case since the Geary Act of 1892, which established detention and deportation in the context of rising Chinese migration to the U.S. Confirmed in 2009 by an ICE administrator, “Immigration proceedings are civil proceedings and immigrant detention is not punishment.” Overstaying a Visa or being in the U.S. without proper authorization is a civil issue, not a criminal one. Yet, the architecture and infrastructure of detention in the U.S. today comprises dozens of buildings designed as prisons, or designed using the same formal and material components as prisons.

Texas plays a special role in the history of the detention construction industry. The Southwest is (and has been) a place of experimentation when it comes to defining and hardening the boundaries between the U.S. and Mexico. Texas has immigrant processing and detention facilities that date to at least the 1930s, but it was not until the 1990s that what has become a large-scale infrastructure of detention commenced in earnest. In fact, today, Texas has the capacity to detain more migrants than any other state in the Union. The large-scale infrastructure of migrant detention in Texas is possible because private prison corporations have developed new ways to design, build, and manage detention. While only 15 percent of the U.S. prison system is privately owned and managed, an estimated 73 percent of the migrant detention system is owned and managed by about five private companies. Since the 1980s, private corporations have built at least 16 detention centers for the federal government, a count that does not include the county and city jails repurposed or built anew to detain migrants, nor the Criminal Alien Requirement (CAR) facilities erected to incarcerate so-called criminal aliens. In 1970, Texas had the capacity to detain about 1,500 migrants. In 2017, Texas had the capacity to detain over 15,000 migrants daily, comprising about 26 percent of the nation’s detention space.

In the 1930s, a new Border Inspection Station was built in Laredo. This is one of Texas’ earliest formal, federally funded, and purpose-built immigrant processing stations. In this period, after an extensive survey of existing conditions at ports of entry, the Customs and Immigration Bureau recommended the construction of 48 stations built across 11 U.S. states. According to the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), which now oversees extant Border Inspection Stations, these stations were needed in response to the rise of the automobile, changing immigration policy (i.e. the literacy tests and head tax imposed on those entering the U.S. from the southern hemisphere in 1917), and the enforcement of Prohibition. The GSA celebrates the architecture of inspection stations:

These buildings were a part of a larger movement in federal architecture to express the meaning and the strength of the federal government to its citizens present and future. For those entering the United States for the first time, the border inspection station building was what Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty were for those entering by water: the first symbolic expression of the United States and its values.

Designed by the Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury, individual stations reflected the “region and climate where they were located.” Laredo’s station — an institutional building with a stripped down “Spanish style” arched portico — was designed to inspect both vehicles and people.

In the 1960s, El Paso received federal funding to replace its inspection station with a new detention center. This was, in part, a response to the bilateral guest-worker Bracero Program (1942-1964), which authorized hundreds of thousands of agricultural workers to come north. Formal migration spurred unauthorized migration both during the program and after it was formally terminated. The El Paso center was relocated one mile inland from the U.S.-Mexico border. Constructed out of concrete, cinder block, and brick, four rectilinear dormitories housed up to 192 men each. Women and juveniles were detained in separate church and charity facilities nearby. Archival photographs illustrate dormitories lined with windows letting in natural light, and “latrines” including private stalls. In an article titled “U.S. Detention Facility Almost Like Army Camp: Detainees Amazed at Fine Treatment,” the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s district director notes:

The camp was built as inconspicuous as it could be … [T]he absence of watchtowers and strict confinement measures are designed to make life easier to the deportee while in facility. The people detained here are not violent criminals. They merely are charged with being illegally in the U.S. and are awaiting investigation before being returned to Mexico, or whatever country they are from.

Nonetheless, as is standard now, the facility had 12-ft-high fencing topped with electrified concertina wire that set off alarms when touched. Almost 200 men were in 60-ft-by-30-ft barracks with no air-conditioning. Polished steel mirrors replaced glass, which could be used as a weapon or to hurt oneself. An immigration official in El Paso conceded: “Any time you put a fence around a place, you can’t get away entirely from the feeling of prison.”

Before the 1980s, Texas had three main immigrant processing stations, all located at the U.S.-Mexico boundary: El Paso, Laredo, and Port Isabel. In the 1980s and 1990s, apprehensions rose, facility construction rose, and private prison corporations entered the arena of immigration policy. Jenna Loyd and Alison Mountz’s book “Boats, Borders, and Bases” traces the rise of migrant detention to the 1980s, when Cold War politics and policies, coupled with streams of Haitian and Cuban refugees, resulted in new punitive practices and new detention centers. In 1996, President Clinton enacted the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which greatly increased the number of persons eligible for detention. During the 1980s and 1990s, private prison corporations began to construct privately owned facilities that were leased to governments for direct government operation. The private prison corporation argued that it would save the government money in the cost of both construction and housing detainees daily. While these promises were untested, the private sector was able to deliver faster construction (buildings were erected in two to three years rather than five to six), and the government could finance facility construction in new ways. By using contractors for facility construction, the government was able to tap different accounts, accounts that did not have publicly-voted-on budgets. This minimized democratic engagement with, and potential roadblocks to, facility expansion.

In the 1980s and 1990s, just as new prisons and detention centers were being envisioned and built in Texas, the Justice Facilities Review, an annual publication of the American Institute of Architects on “justice architecture,” documented prison design as turning away from notions of rehabilitation. Juries composed of three architects and three practitioners from the judiciary, corrections, and law enforcement repeatedly described prisons as “non-normative environments.” Non-normative environments, also referred to as the “hardening” of facilities, rely on small dark cells, caged recreational spaces, an absence of natural light (replaced by “borrowed light,” where skylights and clerestories are used to channel indirect light in lieu of windows), harsh fluorescent lighting, an increase in use of concrete floors, crude signage, and minimal person-to-person contact. Reduced human contact is achieved by an “indirect supervision concept” that relies on video surveillance, video visitation, one-way glass, and non-overlapping circulation spaces for both employees and inmates that can contribute to a sense that those incarcerated are always being watched while also interminably isolated. By the end of the 1990s, the jurors warned of the consequences of this design: “Feelings were that once a facility is toughened, there may be no going back — it is difficult to rescind philosophical and architecture decisions.”

Construction companies and private prison corporations were incorporating these ideas into both civilian prisons and immigrant detention centers. Since at least 1992, The GEO Group initiated a design/build component into their corporate structure tasked with developing cost-effective technologies to standardize prisons and detention centers, build them off-site, and use prefabricated designs. These design goals have allowed GEO to build detention centers in increasingly rural places. For example, “technology integration” allows video installations to replace face-to-face court hearings or person-to-person visitations, incentivizing and enabling geographic remoteness. New technologies in combination with specific prison layouts attempted to maximize surveillance without increasing staff. The construction industry was especially keen to the fact that “staffing is one cost factor that may be addressed by design.” Design that aimed to lower the “long-term operational costs” of facilities was especially important, since the same companies designing the facilities were often responsible for their long-term operation.

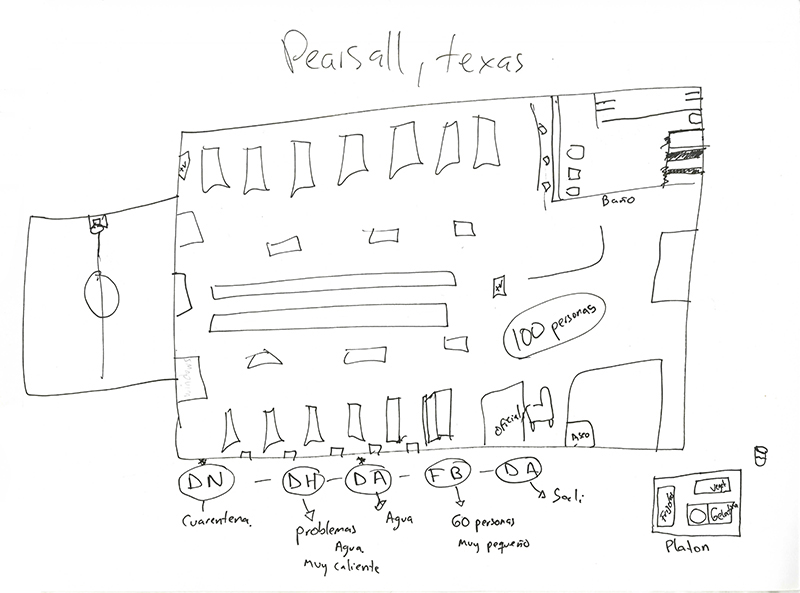

These techniques and technologies are apparent in most of the detention centers in Texas today. In aerial view, detention center footprints cohere with the barracks, telephone pole, radial, self-enclosed, singular and comb layouts typical of 19th- and 20th-century prisons. GEO’s South Texas Detention Facility (known by its location in “Pearsall”) has a ‘telephone pole’ layout, where parallel rectangular spaces connected by a central spine control interior circulation. Classification and categorization are fundamental to Pearsall’s organization; the southern wing houses female and juvenile dorms, and the northern wing houses men in stacked dormitories. Three wings used for solitary confinement radiate from the end of the spine, with a panoptic view from a room positioned in the central crossing.

In an interview with an asylum seeker from Colombia, Miguel, who was detained at Pearsall for four months, the details of the dormitory space came to light. Miguel drew his ‘pod,’ explaining that a large rectilinear space lined with bunk beds on each wall had two long tables lining the center of the room. Bathrooms and showers are depicted at one end; a recreational room is on the other; and a small private room is tucked next to the doorway. He explained that 100 men (from all over the world) slept; ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner; went to the bathroom and showered; prayed; played basketball; or paced in this pod 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with few breaks or exceptions. The bathrooms are not private. Men (and female guards) witness others defecating. The pod has no skylight or windows. The outdoor space is a caged ‘rec room’ with a narrow clerestory at the top that is covered with concertina wire.

Detention facilities have an abstract and generic architecture that conjures a “utilitarian neutrality” similar to Walmart and Amazon facilities, yet the design choices embedded in their form are neither absent nor unimportant. Rather, private prison corporations that view detention as a problem of management rather than a space that shapes daily experience for thousands of people rationalize design choices through a logic of efficiency and economies of construction. A top manager of JE Dunn Construction, an international firm that has built several prisons, detention centers, and Border Patrol stations in Texas, described the driving factor behind detention design as “cost per bed.” This echoes GEO’s design and management philosophy, which emphasizes “cost effectiveness” as one of its prime objectives, achieved by building with future expansion in mind. In so doing, pods are rationalized and noncitizen populations are used as guinea pigs in a laboratory for low-cost technologies of immobilization.

The U.S. government is (still) not driving the design decisions that translate a detaining boom into bricks and mortar — rather, corporate CEOs and shareholders are at the helm of most decisions. In 2007, ICE published a “Design Standards” manual to “establish operational directions and architectural relationships for ICE spaces.” Companies like GEO refer to this manual for detailed information about ICE’s “organizational, operational, and functional” requirements. Plans, photographic illustrations, and dimensions describe ICE offices; even the fax and copy machine room is defined. However, the manual does not provide detailed specifications for the facilities’ primary program — the detainee living quarters. After more than 270 pages, the section titled “Detainee Housing” is blank, labeled only “Contractor Operated.” These spaces are “typically defined and controlled by the Contract Detention Service Provider,” such as GEO. The design of the detainee living quarters exacts great influence over the daily lives of noncitizens in ICE custody; while ICE controls the amount of daylight in its own offices, they deem corporations as better suited to determine migrants’ architectural standards. It is precisely this lacuna at the heart of the program that severs the awesome power of the government to detain from the physical environment in which that power is exercised, suggesting a moral abdication by the state.

Although what has become a crisis of detention today would not be immediately solved if the government resumed ownership and management over the detention infrastructure, public processes and public facilities are an important means toward greater accountability, responsibility, and a higher moral purpose. Serious debate about whether or not these facilities are warranted at all should be occurring within the public arena, not driven by the financial interests of corporations. Private corporations make critical decisions about siting, design, and management that are motivated by profit and responding to shareholders rather than a broader public or international diplomacy. This results in increasingly punitive spatial settings for migrants in detention, with profoundly harmful effects on the migrants themselves.

In the 1930s, the government viewed immigrant processing stations as the place where newcomers encountered “the first symbolic expression of the United States and its values.” Today, that is still true. Men, women, girls, and boys come to the U.S. for all sorts of reasons. Currently, the U.S. mechanism for interfacing with and processing people, to determine who can stay or what a person’s options are, is to throw people in remote prisons with another name. In addition to Texas’ infrastructure of detention being demoralizing, dehumanizing, and a violation of human rights on innumerable fronts, it is literally the material artifact that announces to newcomers and the world who Texas is, and by extension, who the U.S. is as a nation. We, as a nation, are as good as our spaces crafted to receive newcomers, and the symbolic expression embedded in the contemporary landscape of detention is all too clear.

Sarah Lopez is an associate professor at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.