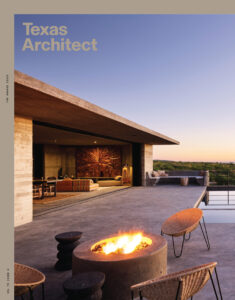

The Awards Issue

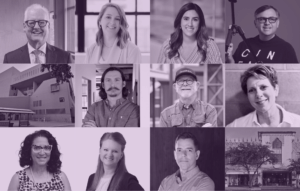

2025 Design Awards: The Jury

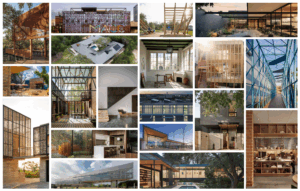

Built to Inspire

310 W Grayson

979 Springdale

Burnet Place

Courtyard House

Center for Medical Education and Emerging Viral Threats

ECC Creative

Elemental Home

Federal Street Restoration

Isidore + Nicosi

Lake Belton House

Learning Pavilion

Mexican American Cultural Center

Pleasant Valley House

Rancho Toma Tres

Round Rock ISD Aquatic Facility

Singing Hills Recreation and Senior Center

Stealth House

Westview Residence

Wolf Ranch River Camp

More from this Issue

View All Articles

Oct 16, 2025

Just after midnight on June 4, 2021, flames cut through the heart of downtown Marfa, smoke curling up from the…

Oct 16, 2025

The name Page has had a storied presence in the world of Texas architecture for more than 125 years. In…

Oct 16, 2025

Driving down FM 969 in Austin, one would never imagine that just off the road lies one of the world’s…

Oct 16, 2025

The Texas Society of Architects announced the recipients of its 2025 Honor Awards on July 17. These awards recognize exceptional…

Oct 16, 2025

Known for its “Enchilada Red” exterior and bold geometric profile, the San Antonio Central Library offers a Texan take on…

Oct 16, 2025

The original prototype is the one all successors aspire to emulate, its best qualities serving as a north star for…

Oct 16, 2025

On July 24, the Texas Society of Architects announced the winners of its 2025 Studio Awards. The program recognizes exceptional…

Oct 16, 2025

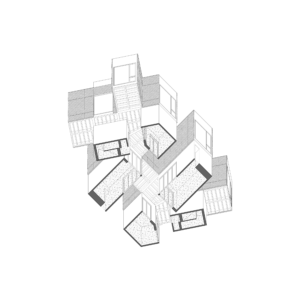

LUTZ OFFICE “We appreciated that this project rigorously deployed self-similar volumetrics in order to accommodate multiple families, produced compelling renderings,…

Oct 16, 2025

CLOVISBARONIAN “Amongst all the projects, this building had the most compelling, thoughtful, and consistent relationship to its site. The way…

Oct 16, 2025

STUDENTS:APARNA PRABU, ALFRED RIVERA, AND EDWIN TOVAR PROFESSOR:RAFAEL B. DURAN OF FERAL DELTA II STUDIO GERALD D. HINESCOLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE…

Oct 16, 2025

DLR GROUP AND ROOT ARCHITECTS “This project showed a lot of ambition for a public building type that is a…

Oct 16, 2025

CORGAN “There’s the implication that the project is capable of producing different microclimates by atomizing the massing of the building,…

Oct 16, 2025

NORVERTO DIAZGERALD D. HINES COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON “The construction methods—lashed together bamboo structure and thatch—are…

Oct 16, 2025

Z4A ARCHITECTS – RAFAEL B. DURAN & OPHELIA MANTZ COLLABORATORS: DIEGO CONTRERAS, MILI KYROPOLOU RENDERINGS: SIMON CHIQUITO “This project drew…

Oct 16, 2025

STUDENTS:JOSEPH HSU AND ELLIOT YAMAMOTO PROFESSOR: JESUS VASSALLO RICE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE,RICE UNIVERSITY “We thought the double roof was an…

Oct 16, 2025

AGENDA ARCHITECTURE “This is a scale and type of building that is being built many times across Texas and elsewhere…

Oct 16, 2025

Reflections on the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale

Oct 16, 2025

Supporting local manufacturers helps firms reduce shipping costs and delivery time, earn LEED credits, employ members of the community, and…

Oct 15, 2025

At its annual awards ceremony on March 1, AIA Fort Worth recognized the recipients of its 2024 Student Design Awards.…