Old Note

The wind whistled you in behind the springtime

Float, Old Note, new among my mind

You hold the note, the note just moves to move mine

Let go the note and so move everything

…

And there I met another note long buried

And sat upon its shoulders was a memory

A home but see, above me’s gone so noisy

I almost think I do not recognize me

Feathered friend, dig up and resurrect me

I long to live among the song of birdies

A lawless league of lonesome, lonesome beauty

Skies and skies and skies above duty

…

—Excerpt from the song “Old Note” by Lisa O’Neill

I recently stumbled across the music of Irish singer-songwriter Lisa O’Neill, her song “Old Note” resonating in a profound way. Her style hearkens to the mournful ballads of traditional Irish music, and her lyrics touch upon a feeling of something ancient and primordial. Marrying the melodies of a bowed hammer dulcimer, a shruti box, a harmonium, and a bowed upright bass, O’Neill paints a landscape depicting our profound connection to nature—the way humanity has lived for most of our history on this small planet.

Preceding her performance on NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert series, O’Neill describes the origins of the song. “It’s about how we communicated before we started writing things down,” she says. This is termed orality, and it is the way our world’s indigenous cultures communicated information about the environment, astronomy, and the plant and animal life around us. O’Neill says: “Even when each person came into the world, it was all communicated through this map of music. I think with the hum of the cities today, we’re sort of losing that sense of music in nature.”

Though the environmental threats of pollution, biodiversity loss, and a warming planet have been well documented, there is another threat that is beginning to catch the attention of researchers, environmentalists, and public health advocates: noise. The knowledge that excessive volumes can lead to hearing loss is widely understood, but it has been largely explained through the lens of the importance of avoiding loud music or taking necessary precautions when operating heavy machinery. What has been less understood is the onslaught of aural microaggressions of typical city dwelling—the hum of the traffic, the wail of a siren, the thud-thud-thud of a jackhammer.

Writer David Owen reported in a 2019 article published in the New Yorker that studies show that excessive exposure to loud environments can lead to not just hearing loss but “heart disease, high blood pressure, low birth weight, and all the physical, cognitive, and emotional issues that arise from being too distracted to focus on complex tasks and from never getting enough sleep.” Not only this, but noise pollution affects our nonhuman friends as well, with “effects that can be as devastating as those of more tangible forms of ecological desecration.” In this same article, Les Blomberg, the founder and executive director of the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse, laments: “What we’re doing to our soundscape is littering it. It’s aural litter—acoustical litter—and, if you could see what you hear, it would look like piles and piles of McDonald’s wrappers, just thrown out the window as we go driving down the road.”

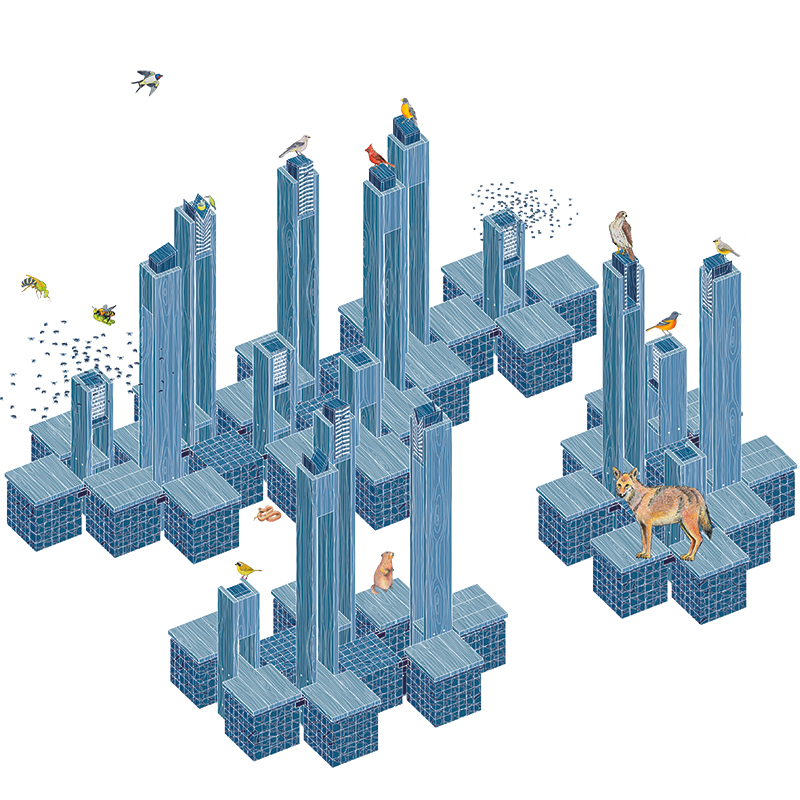

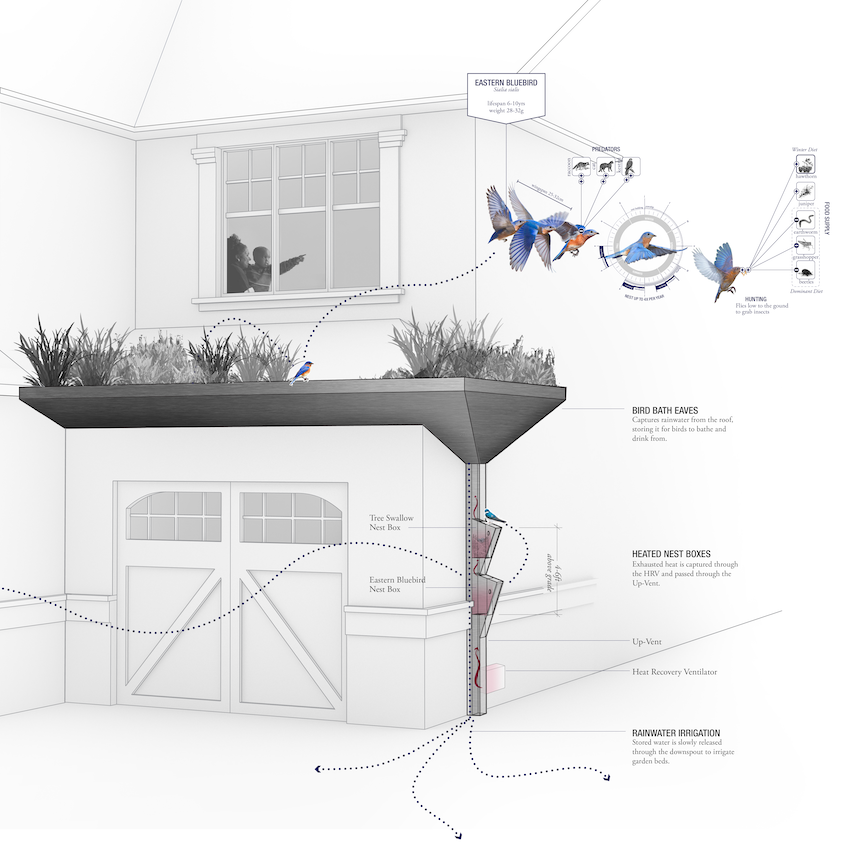

Studies in recent decades have also led to the discovery that noise pollution can disrupt the migratory patterns of birds through a stress-induced drop in body weight and can even cause our feathered friends to flee altogether, with one study citing a 28 percent reduction in bird population when noise was introduced to an otherwise wild environment. Another “accidental” study was performed in 2001 as a group of researchers measured concentrations of stress-related hormone metabolites in the feces of whales. The metabolite concentrations fell unexpectedly in September 2001 and subsequently rose again. The scientists later realized that this reduction of stress in whales coincided with the temporary pause in ocean shipping following 9/11.

The places we build, as well as construction processes, have far-reaching impacts beyond what many of us have imagined. This issue highlights both the poetry of the natural world as well as some pragmatic considerations in how we can better care for it. While the litany of considerations for how to be better inhabitants of this planet can often feel overwhelming, if nothing else, I urge you to step outside the din of the city to reconnect with nature’s eternal songs.

Anastasia Calhoun, Assoc. AIA, NOMA, is the editor of Texas Architect.

Also from this issue