Time Tells

They just don’t make ’em like they used to.

Why has this sentence become ingrained in our collective consciousness? Surely we have all seen or perhaps owned an old appliance, vehicle, tool, or even building, that has endured to the present. The idiom is true in that the means and methods by which things are made and buildings are constructed have changed over time, but are buildings built many years ago really superior to contemporary structures in terms of longevity? One only has to drive around any of Texas’ biggest cities to see large buildings being constructed with dimensional lumber (stick-framing), when the same buildings would have utilized load-bearing masonry decades earlier. Do the methods and systems employed to construct buildings today create long-lasting structures? Does the contemporary development climate prioritize longevity? Is building for longevity always desirable?

Historically, people constructing buildings had to work with what was readily available in their immediate environment. This does not just begin with the European settlers, for people had been building in Texas long before their arrival. The Caddo and Wichita peoples, who inhabited North and East Texas, built large, circular-shaped houses — wood structures covered in thatch — due to the abundance of timber in the immediate vicinity. This locally adapted building technique predated the arrival of Europeans by hundreds of years, and yet seems to have played very little part in informing the building techniques of those settlers.

The Pueblo people of the Southwest (including areas of West Texas) built with adobe. This material is extremely locally focused. They shaped mud into bricks, then left them in the sunshine to dry before using them to construct dwellings that are quite well suited to the desert climate. Often, plaster was applied to the interior and/or exterior face, further preserving the adobe bricks. Wooden beams supported wooden roofs. There are many adobe ruins still standing, and the material is still used for buildings in the region today, a testament to the longevity and continued relevancy of this building method, which, because it is unfired, has a low carbon footprint. Other examples of contemporary unfired earth construction, in the form of rammed earth, though somewhat rare, can be found as far east as Central Texas.

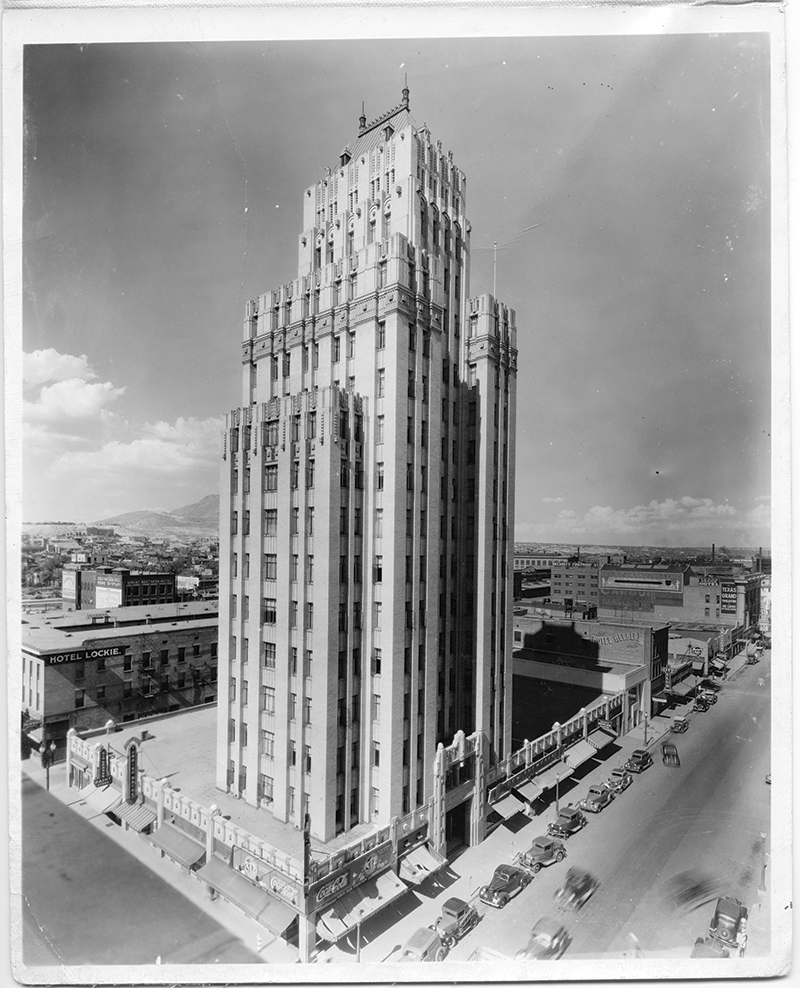

As Texas was settled by Hispanic and then Anglo immigrants, in the 17th and 19th centuries respectively, these people employed construction techniques imported from their homelands, adapting locally available materials to their purposes. European settlers in East Texas, for example, may have rejected the natives’ built forms but readily utilized their local timber, building rectangular one- and two-room homes from logs. Another and much more recent example of local sourcing and adaptation can be found in El Paso, where, in the early 20th century, the first high-rise buildings were constructed with reinforced concrete. This was quite innovative for its time, as the high-rises in cities such as Chicago and New York were being constructed with steel framing. Due to El Paso’s relatively remote location, shipping large steel members was cost-prohibitive, whereas rebar was much more economical, and the remaining materials for concrete were much more readily available locally. The El Paso firm Trost & Trost was responsible for many of these innovative buildings throughout the Southwest. The lack of availability of traditional building components forced this local innovation.

As the 20th century progressed, building components such as dimensional lumber and metal framing began to be mass-produced. This development greatly increased the speed of construction, leading builders to favor these systems over those relying on time-consuming load-bearing masonry or unnecessarily robust concrete. Additionally, the country’s transportation infrastructure improved, making shipping building materials long distances less onerous: Local innovation was no longer necessary as economical materials became widely available regardless of a proposed building’s location. Often in historical construction, the use of systems we perceive as more “robust,” “permanent,” or “solid,” were simply the most economical systems available to the builders at the time.

Today, when a building is being contemplated, the priorities of the initiating party dictate the constraints by which the building method/material/system is selected. Stephen Price, a structural engineer and principal at Datum Engineers in Dallas, says that, for projects he has been involved with throughout his career, “it is very rare that the owner’s top two priorities are not budget and schedule.” This is why it is uncommon to utilize solid masonry or extensive poured-in-place concrete for a typical single-family home. The speed with which a stick-framed house can be put up — and its relatively low cost when compared to other options — make it difficult to eschew this technique in favor of more expensive systems. It is only when owner/builder priorities shift that a different or nonconventional solution can occur. If, for example, one lives in Tornado Alley and wishes their home to withstand a direct hit, they will build with reinforced concrete or steel framing in order to resist the extreme wind loading. But this will come at great sacrifice to budget and schedule.

Used for residential construction for nearly 200 years, dimensional lumber framing is not inherently temporary. We have many examples of historical homes built with dimensional lumber that still stand today. The difference, here, is one of maintenance, which becomes extremely important for a stick-framed building. The protection from moisture becomes paramount as one seeks to maximize the longevity of this construction type. One must take a great deal more care for dimensional lumber-framed buildings than, for example, a concrete structure. This being said, when asked what construction method he would choose to build his own home with, Price said, “There’s nothing wrong with stick framing, assuming it is done correctly.”

Concrete, in many forms, is a very common building material in Texas. It is solid, hard as rock, and gives the impression of permanence that wood construction can lack. Concrete is favored by architects for its ability to be molded into any shape, for its aesthetic qualities, and for its strength and durability, often achieving much thinner sections than a comparable wood or metal structure. We have all seen the images of the abandoned concrete pillboxes along Normandy’s beaches, and the prefab concrete ghosts of Pripyat, Ukraine, near Chernobyl, the concrete seeming to outlast all other man-made elements. It is not invincible, however; proper maintenance and protection from moisture are essential for concrete structures as well. Moisture infiltration can result in rusting and swelling of the rebar, which causes the concrete to spall. It may be able to resist more moisture infiltration and neglect than wood, and it may deteriorate much more slowly, but, in the end, it will suffer the same fate.

Concrete’s durability, however, must be considered alongside its high environmental cost. The concrete industry worldwide emits more CO2 than any country besides the U.S. and China. It also requires large amounts of another precious resource: water. With extended droughts becoming more frequent, diverting large amounts of water to concrete production, especially in dry regions, can be problematic for ensuring a reliable drinking water supply. Sand is also heavily used in concrete production, and sand mining is its own environmental catastrophe, responsible for 85 percent of all mineral extraction from the earth. Sand mining, largely undertaken to feed the demand of the worldwide building industry, destroys the natural ecosystems of lakes, rivers, and coastlines around the world.

This is a challenging issue in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where the required fire ratings and local contractors’ proficiency and familiarity with concrete often lead to its selection as the primary structural material. It is often cheaper than steel framing in this market.

One “new” — yet incredibly old — system just beginning to make its resurgence in Texas is heavy timber. Heavy timber, primarily in the form of glue-laminated structural sections, provides a welcome alternative to the binary choice between steel and concrete for commercial buildings. While this method is currently not standard practice, there are now multiple examples of heavy timber buildings recently constructed in the state, including: the Soto Building in San Antonio by Lake|Flato with BOKA Powell; First United Bank Fredericksburg by Gensler; and 901 East 6th in Austin by Delineate Studio and Thoughtbarn.

The reality is that any construction method, including stick-framed buildings, can last for hundreds of years, given proper maintenance and protection from moisture infiltration. However, sometimes old buildings are compromised by other sources. In North Texas, often what leads to an old house’s demise is not the deterioration of its framing system, but rather the inadequacy of its foundation. It is not uncommon to see old wood-framed houses dipping and sagging as if they are riding a wave. There is not much that can be done for these buildings.

As catastrophic events that were once exceedingly rare become more commonplace, architects, owners, and all involved in the creation of new buildings will need to be prepared to evaluate their priorities. Instances such as the Dallas tornado of October 2019 and Hurricane Harvey and its destruction in Houston and other Gulf Coast communities have clearly made the case that the way we typically build is not capable of withstanding nature’s destructive forces. If we did not have to contend with these events, then buildings erected using any viable construction system and properly guarded against moisture infiltration would endure for many years.

However, in our context, we must now be aware of these increasingly frequent hazards, and we cannot simply hope our building will not be affected. Rating systems such as RELi (from the USGBC) contain guidance on how to address challenges posed by increasingly severe natural events in the design and construction of our buildings. If and when a building does come to the end of its life, either through destruction via natural forces, age, or intentional demolition, the resulting pile of rubbish must go somewhere. We have to consider the component parts of our buildings, and ideally, we choose elements that do the least harm once the building is gone. Can we ensure that the majority of this pile is able to be reused?

However, a pile that was once a building, even if its contents are able to be recycled, cannot stand as a reminder of the past. Buildings form our physical connection with history, and once one is removed, society’s connection with its particular contribution to the past is severed. History becomes an academic exercise, not something that is seen, felt, and experienced. For this reason, the longevity of all building types is of cultural importance. One Dallas neighborhood experiencing this reality is the Tenth Street Historic District, a former freedman’s town. Slowly, over the years, houses were torn down (often by the city) rather than repaired, and now this neighborhood with vast historic significance has been all but erased.

The reality is that most residential buildings are constructed using the “humble” method of stick framing, so it becomes extremely important to ensure their longevity by correctly implementing all waterproofing and flashing, and ensuring necessary maintenance over the building’s lifespan. This building type is the most prone to deterioration or destruction, and therefore requires the most effort, time, and money to make it last. For families and neighborhoods where resources are scarce, this is extremely difficult. Therefore, over the lifetime of these buildings, this construction type disadvantages individuals and neighborhoods with limited financial means. As architects, we should be aware of this as we design for the future, especially if we are providing design services to nonprofits, community development corporations, and the like. Think about resilience and future longevity. Think about the state of the neighborhood in 50 or 100 years.

After researching and writing this article, I am convinced that “they don’t make ’em like they used to” is in fact true, but also quite nuanced. Yes, certain aspects of historical construction were more robust (2x4s were actually 2x4s at one point, and load-bearing masonry was more common), but modern construction can have every chance of being as long-lived. We have more tools at our disposal today to ensure our buildings’ longevity; we simply must make sure they are employed correctly. However, often they are not, and we do need to consider the reality of the built structure, not simply how viable the construction method is theoretically. Getting inventive with materials and asking questions regarding priorities at a project’s onset are ways to begin moving the needle. If we can create places that are able to withstand extreme natural events, the passage of time, and extended use by people, then perhaps we can redeem the saying, and “they don’t make ’em like they used to” can instead become a compliment to new construction.

Andrew Barnes, AIA, is the founder of Agent Architecture in Dallas.