New Sacred Geographies

Students who contributed input and drawings to this article:

Abel Guajardo; Alejandro Luis Guerra; Annie Benavidez;

Clara Barba; Cyrus Melendez; Daniel Ivan García; Diego Hernandez;

Jesse Gonzalez; Laura Carolina Hernandez; Yoana Penelova

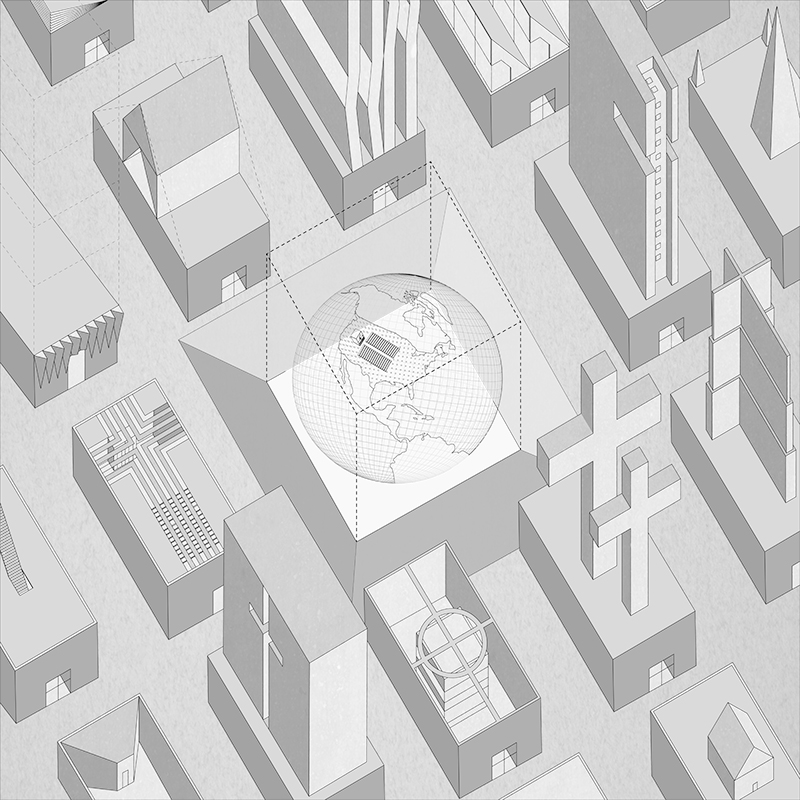

In 2016, my undergraduate studio at The University of Texas at San Antonio explored how architecture — mostly acting as the physical embodiment of religiosity itself — can provide answers to questions regarding the relationship between geography and worship. How has this relationship stimulated new forms of worship on a geographic scale? Can architecture be the lens for novel figurations of religion and how religion has affected the aesthetic and discursive forms it has presumably taken?

With the historic and theoretical foundation developed by my

(doctoral) research, in the studio we utilized different mapping and drawing techniques, not only to recover the relationships among worship, materiality, and representation, but to unearth the mechanics behind the operations and the way ritual, religious practice, and agency have defined and redefined the metrics necessary in designing novel representations of worship in American history.

In “America,” Jean Baudrillard framed secularism and its relationship to the environment as part of a set of critical cultural observations in which he juxtaposed Europe and the United States in a similar context. In his chapter “Utopia Achieved,” he affirms, “What in Europe had remained a critical and religious esotericism became transformed on the New Continent into a pragmatic exotericism.” His observations not only render religion a sphere or representation of reality, but relegate it to one in which the distance between the secular and the sacred — or, as I would argue, its ontological trajectory — becomes less about the space itself than about how visible and invisible systems eliminate divisions between the two. Rather than to seek the essential understanding of religion in singular objects, we were interested in examining the amorphous placelessness — how it registers in new spaces, new rituals, new aesthetics, and new understandings of how the sacred and the secular are intertwined, inseparable, and sometimes invisible to the apathetic eye.

Geographic

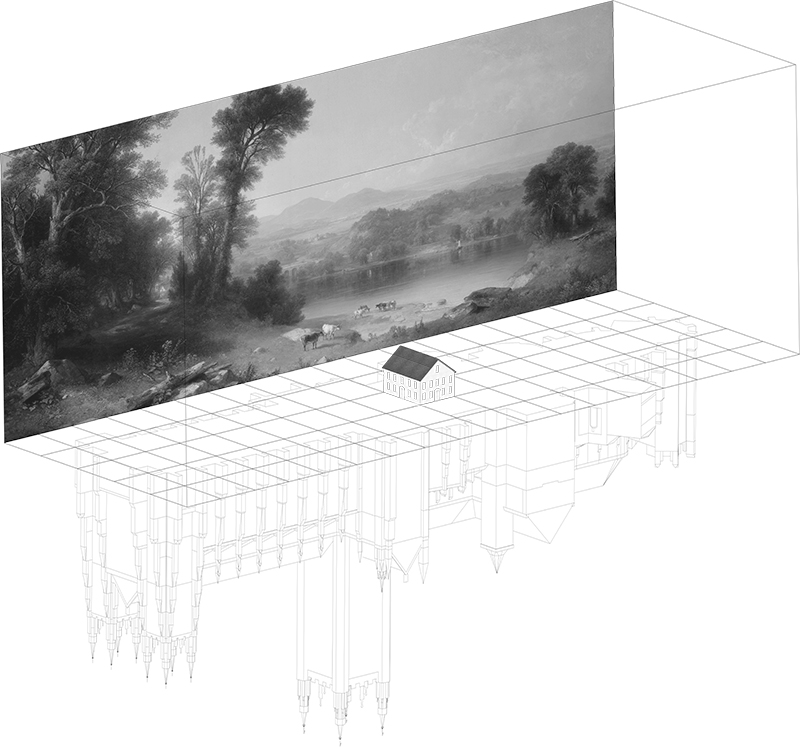

We considered the so-called “geographic” design paradigm as a framework because it reveals the isolationism of religion to be something that happens exclusively inside — that is to say, traditional religious architecture separated production and consumer culture into two distinct spheres. The geographic not only allows for a new understanding of where religion might be located, but it also questions its spatiality, which on one hand is about legibility, and on the other about cognizance.

For instance, the geographies produced by the 17th- and 18th-century pastoral landscape not only shaped certain religious ideologies but also inspired the radical transformation from the cathedral to the meetinghouse. The role of camp meetings in the wilderness set the stage for revivalisms in urban environments, while industrialization, consumerism, and globalization all informed new religious typologies while shaping and transforming the geography they were part of. As a result, the foundation was set for new rituals, new practices, new aesthetics, and new worship spaces that expanded the traditional figuration of churches into geographies or geographic objects, or both.

Elements and Aesthetics

One might argue that architecture in general — and, more specifically, sacred architecture — has not only lost its ability to critically mediate among ethical positions, value systems, and the environment, but that it has also lost its aesthetic expressions. What I have called superordinary served as the framework for breaking down the heavily intellectualized and contested relationship between the theory of sacred architecture — in which “architecture” is subsumed by the “extraordinary” and extends itself through it — and its physical manifestation. In a variety of drawing exercises, the students explored the aesthetics behind what Baudrillard and Alexis de Tocqueville characterized as the “utopianism” and “pragmatism” of American civilization. Characterized as an aesthetic expression, somewhere between extraordinary and ordinary, one idealizes the design of the environment and the places that house (extraordinary) representations, and the other fetishizes the absence of them. As a matter of fact, absence is what unfolded in scale and complexity, to the extent that it not only displaced previously established hierarchical orders and interventions, but it also dismantled what formerly lent it beauty, in the construction of new geographies of access, control, place, and relation. As a result, the way we represented worship — as a latent geographic influence, questioning the narrowly defined monumentalization of traditional churches — set the foundation for new religious ontologies and a new visual narrative in the American landscape.

Spatiality and Materiality

Whether embedded in design traditions, in intellectualization, or instead concerned with surrounding environmental conditions, materiality is ascribed to cultural and ideological values and performative aspects in sacred architecture. Our drawings show how the examples of worship space we explored are transgressing the traditional understanding of materiality — or the overt phenomenologization of it — by transcending the earthly and the divine by means of the profane. In Robert Schuller’s drive-in walk-in church, for example, the parking lot became the center space between the service on the inside of the building and the American cultural landscape defining the larger framework. Extending from the three-dimensional pulpit through the glass facade of the church into the windshields of the cars, Schuller’s church completely reconceptualizes the relationship between religion and space, perception and representation, abstraction and reality, and the way the sacred is materialized (or, as a matter of fact, dematerialized) in architecture.

Other examples discuss material transformations and organizational frameworks. For example, Benjamin Latrobe’s camp revivalist meetings de-familiarized the seeker by completely obliterating any material boundaries between worship and the environment; Aimee Semple McPherson’s radio tower “Angelus Temple” expanded religion into unseen territory; Billy Graham’s “Man in the 5th Dimension” pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1964 radically dematerialized religion and worship into the moving images of a film; and, in Richard Neutra’s Garden Grove drive-in church, radio signals transmitted the service into cars parked outside. These examples, and many others we studied, not only questioned the material presence of religious services, but also expanded how religion and the geographic reimagined material boundaries between the inside and the outside, the sacred and the profane, the mass (consumerism, media) and the needs of the individual; all ascribed to materiality another form of spatiality, consumption, or even mobility, not only to render religion legible, knowable, and actionable, but also to offer new experiences.

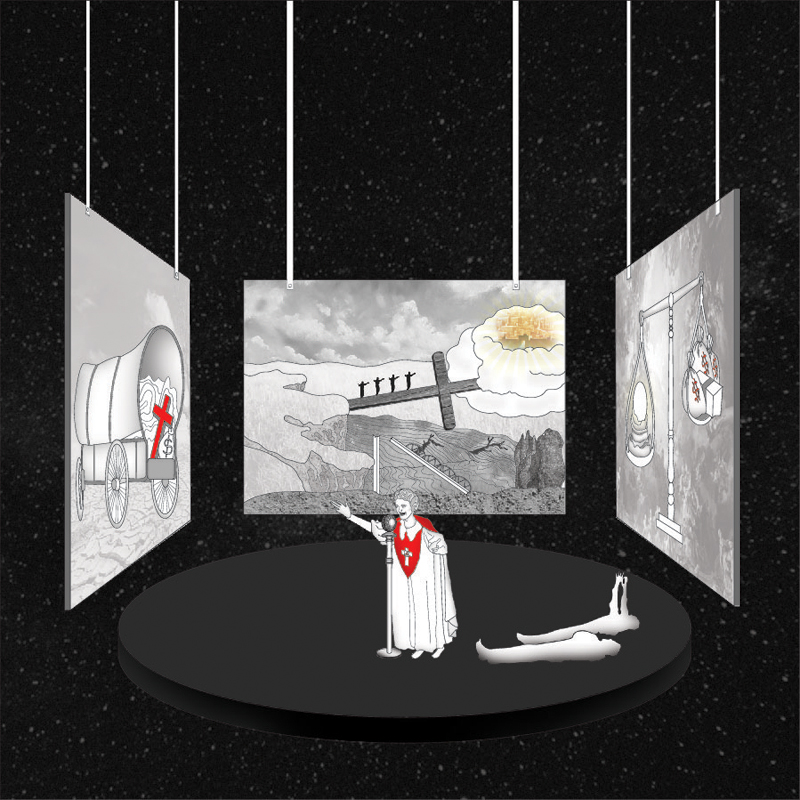

Representation and Rituals

The management of currencies and rituals also plays a crucial role in setting the foundation for new metrics of religious spatiality. This is best understood through the characteristic adaptability that reverberated in a revolution of architectural forms, and a programmatic dexterity that radically redefined the roles of place, structure, spectator, interior, and exterior to create new forms of reality architecture, or super-reality: a space in which the exteriorization of the inside, as well as the interiorization of the outside, continuously alters its borders, in the words of Andy Merrifield (“The New Urban Question”), “gobbling up everything and everywhere in order to increase (surplus) value and accumulate capital.” For example, the emphasis on physical characteristics such as accessibility and location was largely recognized. And churches, like businesses, needed to accommodate a steady flow of people, which required surplus parking. Robert Schuller commented: “With the development of shopping centers, Americans had become used to the convenience of easy parking. But a look at reality gave evidence that parking wasn’t always easy for churchgoers at ‘superchurches.’” Churches like Schuller’s staged parking and utilized the automobile, or other means of transportation, as critical aspects of their religious practice. In fact, automobiles were such an integral part of new religious philosophies of the 1950s and 1960s that they presented a direct analogy for the extension of religion into the geographic, connecting the larger cultural landscape with the collective and the self.

Agency

In conclusion, the studio did not exclusively focus on the accomplishments of the architect; rather, we were interested in how the idea of architecture grows with the client, custodians, culture, and the geography it is a part of. For example, the participatory spectacle of church services was not only determined by the charisma of the presenter; but it was also a collaborative product in a causal relationship between individuals and a collective agency. Creativity emerged from the audience, and the ambiance of the performance merged with the stage, which expanded beyond the spatial boundaries of the church and was mediated by traditional images, location, labels, language, and signs. As a result, it transcended everything that had previously made architecture a source of architectural meaning, process, and probability, reclaiming new possibilities for physical manifestations for sacred or religious architecture in a secular world. It is about locating the geographic as the source of architectural meaning in the construction of relationships somewhere between spatiality and representation.

With the research we have conducted, we hope to challenge these positions in order to recast the geographic church as an element of transcendence that not only helps us to perceive and draw the finest realities (and immaterialities), but also inspires innovation and invention in the construction of new meanings and aesthetics. These religious leaders, or what they propagate, have contributed to a better understanding of geography and architecture. They have influenced the cultural and environmental landscape as clients, if not custodians, of God, and thus they have made tremendous contributions to the American landscape and, arguably, to architectural discourses.

Antonio Petrov is a professor at UTSA College of Architecture, Construction, and Planning.