On any day along South Congress in Austin, you might pass a line of people in front of a brick wall with no door. They are waiting to pose in front of the cursive words “I love you so much,” painted in red on a mint green background that covers one exterior wall of Joe’s Coffee. Painting and color evoke our emotions and cultural sensitivities. These psychological reactions magnify our relationship with place when the painting and composition of colors are integrated with the physical architecture of the city. If the simple “I love you so much” mural can become a significant landmark for Austin, then what effect do the socially charged murals of Mexico City’s civic architecture have on local navigation and sense of identity in that place?

Although a mural may be distinguished from a painting by the manner in which each is framed, the mural is still studied within a frame — be it a wall’s face, a page in a book, or a PowerPoint screen. While a painting lives within the curated space of a gallery, a mural lives within the architectural space of a city. In Mexico City, I hoped to elucidate the frames around its murals by asking locals and tourists to draw mental maps of two famous murals, the buildings that house them, and the subjective urban frame in which each resides. The idea was to develop a living image of the city along with the cognitive presence of its iconic murals.

Since the talud-tablero at Teotihuacán, art has driven architecture’s social function in Mexico. Beginning after the Mexican Revolution, 20th-century Mexico City was marked by artists such as Diego Rivera, architects such as Mario Pani Darqui, and planners such as Carlos Contreras Elizondo, who collaborated in the creation of a visual narrative for a modern city with public institutions: ministries, schools, housing, museums, and the Ciudad Universitaria. Their collaboration had a precedent: Thousands of years earlier, in fact, the practice of integración plástica — a marriage of painting, architecture, and sculpture — became central to Mexico’s architectural and art history. The integration of colorful arts and formal architecture represents not only a combination of the two in a building, but also a singular means of expressing cultural identity and connection to place in one of the most densely populated cities on earth.

My project was inspired by the work of the urban designer Kevin Lynch, who, while at MIT in the 1950s and ’60s, emphasized the importance of subjective reading and cognitive mapping of the city. He begins with a definition of “public images” as “the common mental pictures carried by large numbers of a city’s inhabitants: areas of agreement which might be expected to appear in the interaction of a single physical reality, a common culture, and a basic physiological nature” (Kevin Lynch, “The Image of the City,” 1960, p. 49). Lynch’s “Three Cities” research used two groups of map-makers: “a systemic field reconnaissance of the area” by a “trained observer,” and “a lengthy interview … held with a small sample of city residents to evoke their own images of their physical environment” (ibid., p. 15). The resulting interviews helped Lynch generate cognitive maps constructed from a unique language of symbols and lines: paths, edges, nodes, districts, and landmarks.

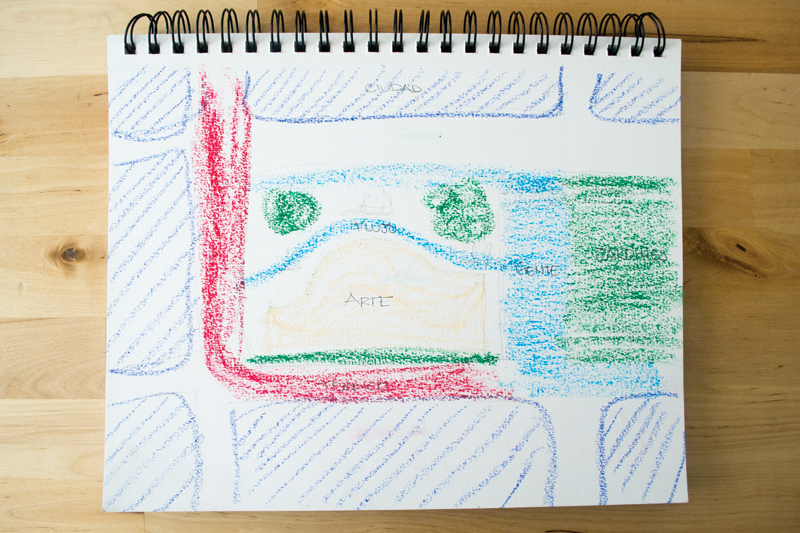

As architects and designers, we translate phenomenological experience to formal expression for our clients. In this project, I wanted to give each participant the freedom to impose their own aesthetic, lest something be lost in my formal interpretation of their descriptive experience; the process of rendering interviews as a single set of my own drawings would have isolated their communicated responses from their visual understanding of place. Instead, I gave each participant a 9-in-by-12-in piece of paper, a set of 12 colored oil pastels, and a pencil: I let them draw their own cognitive maps. Oil pastels offered a loose material unfamiliar to both architects and non-architects. Instead of perfectly straight streets and geometries, the oil pastels captured each individual’s expressive hand and forced them to make bold, intuitive strokes. All interviews were conducted in Spanish and, with permission, filmed, though in some cases the interviews had to be transcribed.

On January 5, 2016, I arrived in Mexico City, terrified. This was my first time in the country. College years steeped me in the history of Mexican art, as did months studying and then co-teaching a course in Mexican architecture, and two summers at the New York office of Mexican firm TEN Arquitectos. Not a single “moment” of these framed narratives of art, city, and space allowed me to grasp the multidimensional experience of being there: the tiny ticket counters for airport taxis; the colorful geometries of the houses we passed between Benito Juárez; the monumental experience of the infamous traffic; and the variety of expressive people crowded into cars, peseros, and taxis. The next morning, fully woven into the fabric of the Distrito Federal, I went on the first site visit.

When I did my academic research on the work of Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros, I saw their colorful murals in books. They stood out like beacons amid the black rhythm of the text. In Mexico, I expected the murals to hold the same centrality and distinction in their concrete context. Upon arriving, I discovered that in the patter of urban life, many of the 14 murals on my pre-travel list of sites had fallen into the shadows behind new construction, architectural programs, or implemented boundaries, while some had altogether vanished, and many of the public institutions that housed murals granted limited or no public access.

I had arrived in Mexico to examine the cognitive presence of historic murals in the contemporary image of the city. As I proceeded, the pursuit of my research challenged the physical realities of borders and accessibility of what had been known as a public art movement. The murals most recognized and beloved by participants were part of defunct government offices or institutions, now tourist destinations where tickets had to be purchased to view them. The functioning public buildings with murals were nearly inaccessible to the public, and the guards and front-desk workers seemed unaware of the rich artistic contents of the buildings where they worked. Some murals were impossible to find at their site, and architects I asked suspected that when the buildings were renovated the murals had been moved or destroyed.

For example, I went to the Secretaria de Salud Pública to see one of Rivera’s famous murals. Although officially public, the secretariat was not open to visitors, and several weeks were required to process an application to pass through a gate beyond which the mural lay.

“Are there murals in here?” said one guard. “We have some stained glass windows; you can look at that from the street.”

And at the Supreme Court, the women who checked in officials and visitors knew where the murals were located, but claimed to be unfamiliar with their appearance. In these cases, the murals designed with social intent had been reassigned as paintings of the state.

In zooming around Mexico City over 10 days to check out every site on my list, two sites that were a short metro ride apart are juxtaposed in social circumstance and emotion: Palacio de Bellas Artes and Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco. Each of these buildings wrapped its construction phase during a renaissance of post-revolutionary idealism. The Palacio de Bellas Artes embodies the golden age of Francophile culture and architecture in Mexico under the regime of Porfirio Díaz,* although its construction was slowed in 1910 by the Mexican Revolution. When Federico Mariscal took over the project in 1932, the exterior was completed in keeping with the existing design, but inside the intended Beaux Arts and Neo-Classical detailing were replaced with ornamentation that fused iconography of pre-Hispanic cultures with American Art Deco. The walls of the multi-story atrium and galleries of the Palacio feature work by Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco that glorified Mexico’s mixed indigenous and European heritage, communism, and fruits of the land, instead of the landed gentry.

Meanwhile, Tlatelolco is known today for its Plaza de las Tres Culturas, originally an extension of Tenoxtitlán with a second Templo Mayor complex. The Spaniards built a monumental stone church on the site and adopted a large plaza to demonstrate their conquest over the Aztec empire.

Located only a few blocks apart, these two sites gave rise to cognitive maps of starkly different colors and emotions.

Palacio de Bellas Artes

Approaching the Palacio de Bellas Artes from the metro station is an easy delight. The building’s white marble glows against the smog of Mexico City, which even on a clear day remains in the dust and crowd below the great blue sky. The exterior of the building was crowded with people seated on marble planters that held massive green bushes. Laughter, snapping photos, and conversations rang in the air.† Inside, a visitor steps with awe into history, and the scale of the murals relative to the free-flow circulation around the galleries conceptually separates them from the building’s exterior. The paint, with its intricate details spread across massive canvases, is rich and jewel-like. It is easy to remember that this building has had two lives — the one that built its exterior, and the second, which filled its interior with breath and soul. The murals are large paintings in a winding, multilevel gallery that opens to the atrium below, yet their scale and placement imply that they are the building’s lungs.

I conducted 10 interviews on the Palacio de Bellas Artes, and they were by far the most passionate, overall. Even people I met at other locations wanted to share their admiration and delight and their pride in Mexico City taken from the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Juan Alberto Vega Barreto was nominated by his colleagues at the information table in the Palacio to be interviewed, because no one else “could draw.” He came to the area daily and said that being part of the atmosphere at the Palacio de Bellas Artes made him feel “happy, proud, and fulfilled.” The only word he chose to describe the Palacio was “happiness,” and he would change nothing about it. From the cherry wood-colored desk by the staircase, he described Mexico City as a whole as “an enormous city with a grand, rich culture.”

It was interesting to note the consensus among people while they were in the same building or place. I also interviewed an architecture student visiting with her mother from Veracruz; the communications director at LIGA, Mexico City’s Architectural League; a devout Catholic retiree who had spent her life working at a cafeteria; the concierge from the nearby Westin hotel; the restaurant manager at the Placio; and one of the partners from the young and ambitious architecture firm Taller Veinticuatro. They had all arrived at the Palacio de Bellas Artes with different intentions — to work, on the way to work, to visit and shop in the bookstore, to meditate at the green oasis of the nearby Alameda Central, or to hang out and enjoy the Palacio’s public space.

The interview questions invoked subjective descriptions: the color and emotion of the building, its zone, and the city. These experiential responses are the ones architecture and urbanism generate in everyone, not only in formal connoisseurs. No interviewee was privy to the responses of the others, but when they visited they all felt part of something bigger and monumental: “very small,” “protected,” “happy, satisfied, fulfilled,” “good,” and “intrigued.” Only one person, a tourist from the Yucatan, mentioned the overwhelming chaos of Mexico City. Were these emotional relationships with place related to the architecture? Or were these experiences impacted by the presence of these national murals?

Several participants felt that the beauty of Bellas Artes was inherently linked to the murals. The concierge was uncertain how things might change if the building was stripped of its murals, but María of LIGA explained with conviction: “The building imposes so much that no one enters to see the murals on the wall except to show their children for their civics classes in primary school. Bellas Artes has a foreboding symbolism; the poor do not enter, not because they cannot, but because they still feel forbidden from entering.”

The reality suggested otherwise. Another María, the retired woman who was not comfortable reading and writing in Spanish, came to Bellas Artes and the Alameda Central every month because she loved art. She felt that the beauty of the architecture and art within carried deep spiritual meaning. Asked about the difference between murals and paintings, she considered the question for a moment before answering: “Murals are more important; they are immortal, and although man passes, murals immortalize our culture and history. Paintings are pretty to look at, but they are made by the artist, not by the culture. These murals are made by our culture.”

Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco

At Bellas Artes, the murals are enclosed; in Tlatelolco, the neighborhood is closed.

Colorful layers of paint and integración plástica guard the exterior of Mario Pani’s urban development. The interviews at the Palacio de Bellas Artes inspired gaiety. When I mentioned over dinner with a friend who works in finance that I intended to do the same research in Tlatelolco, he looked bemused and asked to come along. Uber said the trip would take less than 20 minutes from the leafy, elegant streets of the Colonia Polanco where I’d eaten breakfast, but for upper middle-class and affluent Chilangos, there is no incentive to visit the Americas’ first functionalist public housing project, spearheaded by Mario Pani.

While other neighborhoods of Mexico City are so downright dangerous that no one, not even the police, enter, Tlatelolco carries more ambiguity. The Plaza de las Tres Culturas has reviews on TripAdvisor, and UNAM, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, has a branch right next to the plaza. Still, most internet queries yield results about the dramatic history, the 1968 Olympic protests and massacre, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, or the memorialization of the ancient pyramid next to the plaza. So, as I prepared to wander with my camera into an unknown zone in search of murals, I decided to invite along a few friends: a music producer and three architects.

If low-income neighborhoods are happy, then the street is filled with chatter. Music plays from boom boxes or rings out from the windows. In Tlatelolco, parked cars and tentative tianguis line the periphery of the housing complex where it meets the highway. The facade of the building is the entirety of what is known about this place by the general public. It proves almost as difficult to enter the interior of the Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco as to gain access to the murals in the government institutions I visited. There are no gates, but the concrete and brick structures draw a sharp edge around the building’s public contents.

On this Sunday, we pass rows of high-rise apartments, shabby remnants of a former modern glory. Most people outside are men. It is difficult to comprehend how many people live here, because the buildings are more like silent sculptures, and the people like the Virgin de Guadalupe in a Mexican chapel — so easy to visualize, in context, but detached from present reality.

We curve off from a main street, one of the Conjunto Urbano’s boundaries, to traverse the Tlatelolco metro station on an adjacent outdoor path. The station and the parallel pedestrian path feed into a sprawling plaza. Groups of young men and boys stand around talking. Some eye me. When I raise my camera to capture the life of Tlatelolco through the lens, I begin to see that the clusters of men are gathered in surreptitious drug deals.

The people walking outside between the walls stare into our eyes, silently, hauntingly. My friends follow the professor arquitecto Israel López Balan, as he shares the history of the zone. There are bright colors and six vibrant murals by Nicandro Puente. On this trip, it is too challenging to speak to the housing residents. Along the paved sidewalks, shaded by orange steel structures, the locals walk quickly. An invisible wall glides between us and them, separating our interactions.

The original plan of Tlatelolco by Mario Pani aimed to rectify what he called “herradura de tugurios,” a horseshoe slum, titled this way because of the informal, disorganized residential area that workers inhabited on the city’s periphery. While ordering systems in architecture most often demand an aesthetic and mechanical prowess, at the scale of the urban physical composition requires an emotional and psychological empathy.

On a Thursday, I met the energetic and brilliant Tatiana Bilbao — Mexico City-raised and educated, and a leading architect — at her studio to discuss the mural project. A great fan of Mario Pani’s functionalism, she is drawn to the mapping of Tlatelolco. Given the activity in the studio, she only visits there once or twice a year, though she used to go much more often. Bilbao described the “heavy weight, one of history, a very powerful weight.”

“To me, what comes to mind is collective identity, a collective responsibility. A pressure, social repression … political … and inequality. I think the responsibility of an architect with respect to this is very strong. With an architecture, especially one at this scale, one engineers how an entire community lives.”

What about the color of the zone? What colors do you associate with the radius around the housing? Does the integración plástica play any role in improving the psychological condition of public space? The concrete depicts a sugary world of painted orange cream, lemon yellow, and cotton candy pink.

Bilbao contemplates.

“Well, I think that’s very difficult. I don’t think it has anything to do with the color of concrete [or material]. I think that the concrete or color might add certain connotations, but it’s the composition of the concrete that matters. I think in controlling the form and scale you can make concrete very likable. So, definitively, it’s not the color that makes the behavior, but the disposition and composition of the place that makes it. Yes, the integración plástica in Tlatelolco is important; it’s part of the life, but unfortunately, it’s the grey mood that overtakes it. It’s missing something. It’s missing strength. It’s difficult to compete or contest with an architectural composition that is so negative, so massive, so geometric, so functionalist.”

This interaction of architectural composition with color plays out along the streets of Mexico City. The facades incorporate brise-soleil, materials, color, and vegetation in a rainbow of effects, all to illustrate a public narrative on the street and, on the other side, a domestic alternative to the polluted urban reality. On a larger scale in Tlatelolco, the buildings themselves become walls that enclose a less pleasant reality of urban housing from the interaction it needs with the expansive potential beyond.

Wild, Colorful City

After 30 interviews in January 2016, I returned to continue research over the summer with a travel grant from LLILAS (Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies) at The University of Texas at Austin. Mexico City is indeed a city of contrasts. It begins in the airport line, where a collection of people — young people wearing backwards Dodgers caps and baggy clothes; well-starched Mexican businessmen; a team of American filmmakers along with a bespectacled celebrity — shuffles along toward customs and into the wild, colorful city. At the arrival door, after bags are collected and travellers pass through customs, an olive green canvas body bag on a stretcher parades through the exit between arrivals and enthusiastic drivers, family, and friends. Contrast and colors define the Distrito Federal.

In the taxi from the airport, my driver pointed out a furniture warehouse, plastered with teal and maroon advertisements: “Chairs! Living room! Outdoor furnishings! Bedroom!” they read.

“I’ve never seen this place before,” he said. “Do you know how I can tell this place is new? The colors! That maroon purple is my favorite. Look! I even keep this little towel for my face in the taxi; it’s my color!”

When the taxista learns that I came to Mexico to do a project about the city’s murals, color, and their perception within the reading of the contemporary urban plan, he purses his lips pensively.

“Wow! Look over there: Do you like those murals? They grab our attention even as we speed past.”

“Those are colorful [hot pink], but it’s a line of advertisements for running shoes pasted to a construction board. Is that a mural?”

He smirks.

“Do you know the murals of Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros?”

He nods slowly. “Sí.”

“Do you care for them? Did you mostly visit them as a schoolboy or have you looked at them at other times?”

He looks away from the traffic for a moment. “Yes, I saw them in school.” He is not a day under 50.

On one hand, the residents of Mexico City are proud of the murals, as a part of their history and culture. On the other side, it appears that unless you are a muralist yourself, an art historian, or an elementary school teacher leading children through the Palacio de Bellas Artes, murals are artifacts of the past. Even as buildings remain, the integración plástica on their exterior fades into a silent backdrop of civic space. Just as the nuances of architecture often become indiscernible with occupants’ activity, these once-political murals may indulge our view momentarily. More often, Mexico City locals read the murals studied less as markers of public life across urban space than as accessories to the city’s indefatigable clamor.

When I began this project in January, the question was: What larger role or presence do the populist murals carry in a contemporary reading of Mexico City?

In Austin, the kitsch simplicity of murals like “I love you so much” charge them as genius loci, nodes of memory around the city’s commercial and tourism operations. Joe’s Coffee in Austin thrives in an understated masonry building in part because of the playful exterior “adornment.” In contrast, the 20th-century murals of Mexico depict deeper, more complex histories of the Mexican people, and consequently become silent, stoic monuments to the past. This is not to say that the murals of focus in the maps are insignificant, but rather that, at the convergence of color and animation, it is actually these works of architectural art that frame the varying spheres of influence and the diversity of emotion one encounters within the city.

This city is an excursion through contrasts, but the contrasts did not grow up on their own; rather, they are the collision that resulted when two narratives of the city, disconnected in the vast sprawl, encountered one another. Around one mural, the single narrative fragments about the edges of a given public space, flowing back into a sea of stories.

Hannah Ahlblad is a graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

1 Comments

Very moving article and portrait of the spirit of the city! Thank you.